High Participation in the Labour Force

Refugees are commonly seen as a burden to the host society. This prevailing view, however, overlooks the contributions of refugees to national economies and cultural dynamics.

As former Australian Prime Minister (2009) put it: “People who are prepared to pull up stakes and go to a new land—that is going to be different for them—are resourceful and enterprising and will make good citizens for their new country” (p. x).

African refugees are no exception. They actively participate in the Australian economy. They have a high level of participation in the labour force.

In fact, according to the , people born in Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Congo have a labour force participation rate higher than the national average (61%, see Fig. 1).

Whether they arrive with limited educational attainment or advanced qualifications, African migrants fill critical labour gaps in their host countries’ economies.

In a study investigating how refugees contributed to developed economies, (2016) noted that humanitarian entrants do “difficult and dangerous” jobs that locals disdain, including caring for the elderly and cleaning offices.

As migrants and refugees fill those critical jobs, locals focus on higher-skilled and better-paid jobs that they prefer.

Legrain’s observation holds to refugee-background African communities in Australia. The group has low access to professional occupations.

For example, only 10.5% of people born in South Sudan work in professional fields (compared to the national average of 24%).

Africans are overrepresented in the care and support sector, including hospitals and aged care services.

Of those in the labour market, about 10% of people born in Ethiopia work in hospitals, and 13% of people born in Congo work in social assistance services (the national average for the two employment sectors is 4.5% and 2.3%).

Over 11% of working Somali-born Australians are in the childcare sector, the national average being 1%.

Like other migrant communities, Africans with refugee experiences recognise that education can empower them and provide them with skills and knowledge for re-establishing their lives.

A significant proportion of them takes advantage of educational opportunities in Australia (see Fig. 4). During the census year (2021), for example, the proportion of Ethiopia-born people attending vocational and university education was respectively 8.4% and 6.2% (for the Australia-born population, the ratio was respectively 2.1% and 4.6%; for other overseas-born population, it was 3.4% and 5.8%).

Also, high participation rates should clear the problem of low completion rates in higher education. For instance, between 2001 and 2017, around 11,000 Africans from refugee backgrounds enrolled for undergraduate degree courses.

Over the same period, less than 2,000 of them completed their studies. This low success rate has implications for academic preparation at the school level and universities’ ability to provide targeted and ongoing support.

But New Arrivals Are Fewer

Despite their solid economic contribution, fewer people are resettling from the above six countries. Since the mid-2010s, following the eruption of civil war in South Sudan, Congo, Somalia, and Ethiopia, the number of forcibly displaced Africans has increased considerably.

There are around forcibly displaced people in Africa. Unfortunately, Australia’s refugee intake from African countries has declined over the same period.

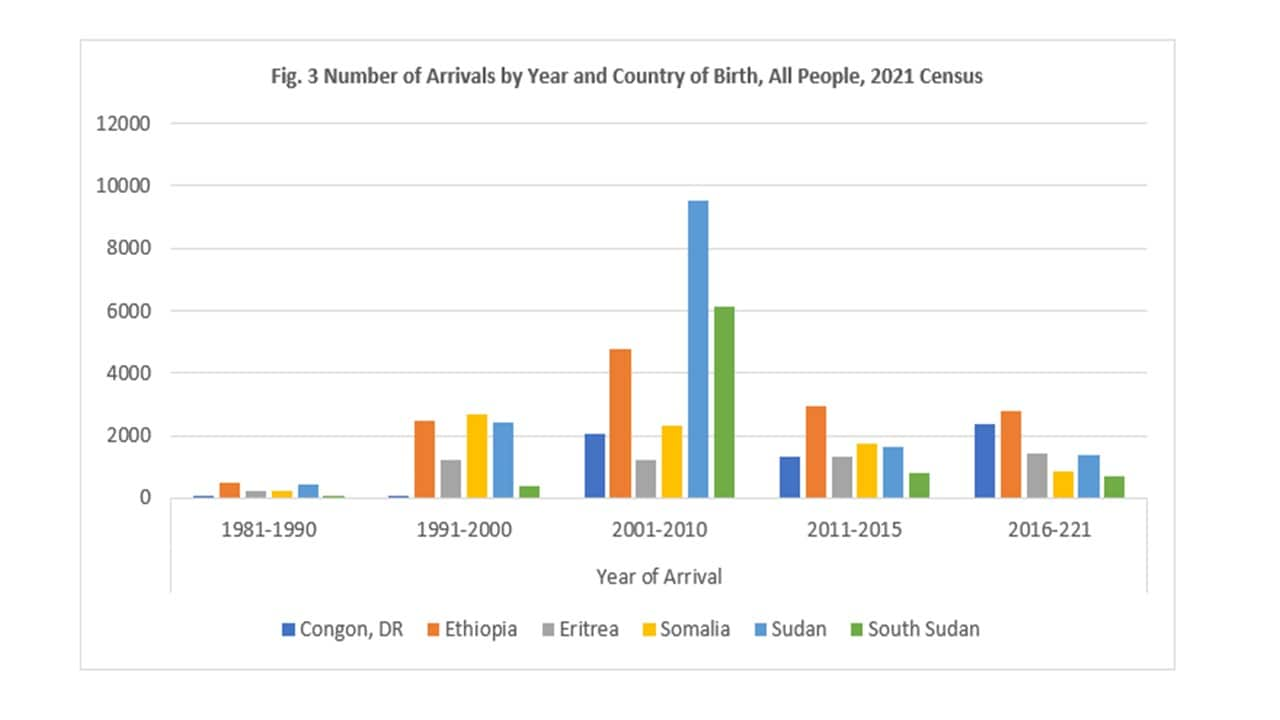

In the wake of the ‘African gangs’ narrative, the number of new arrivals from South Sudan has drastically reduced (see Fig. 3). The reduction in the number of new refugee arrivals from African countries can partly be attributed to the negative and flawed representation of African youth as disengaged and unproductive.

Importantly, discriminatory humanitarian resettlement is not morally defensible.

The Australian Government should be fair in its regional offshore refugee visa provision.

Contrary to the negative representation in the media and political discourse, refugee-background Africa-born Australians significantly contribute to the economic, social and cultural domains of life.

Importantly, discriminatory humanitarian resettlement is not morally defensible.

Refugee-background Africans in Australia are positioned far behind the general population regarding employment rates.

In 2016, the average unemployment rate of people from the leading countries of origin of African refugees was over three times higher than the national average of 6.9%. After five years, the average unemployment rate slightly declined (16.5%), but it was five times higher than the national average of 5.1% (see Fig. 5).

African refugees are more likely to experience “”, meaning they cannot get jobs commensurate with their qualifications and skills.

In Closing

With the fast-paced technological changes in the workplace, those with limited educational attainment might need help finding gainful employment.

The persistence of the problem underscores the importance of policy actions that widen paid work to disadvantaged communities, including those born in African countries.

It is critically important to remove systemic barriers to employment.

Recognising refugees as equity groups in education can help universities provide the necessary academic support.

Investing in refugees is investing in Australia.

Peter Shergold and colleagues said, “Investing in refugees is investing in Australia.” Investment in refugee education increases labour market participation and yields significant national economic dividends.

*** Dr Tebeje Molla is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at Deakin University.