“Free consultation on studying in Australia for all sisters from today, based on my personal experience, hope I can provide some useful information, even a little is good. Something is rotten.”

The was a post by Jiaqi Ren written on Red, a Chinese Instagram-like social media platform, on June 11, just a day after a video of women being brutally attacked in Tangshan, a city in Northern China, went viral and stirred up fury across the country. The video showed three women being attacked because one of them rejected a man’s sexual advances at a barbeque restaurant. In the footage shared online, one of the women was repeatedly smashed by beer bottles leaving her with bloodstained clothing.

The video showed three women being attacked because one of them rejected a man’s sexual advances at a barbeque restaurant. In the footage shared online, one of the women was repeatedly smashed by beer bottles leaving her with bloodstained clothing.

CCTV recorded a group of men attacking three women in a restaurant. Source: Reuters

Too scared to stay

Ms Ren told SBS Chinese bluntly that this attack event was the “last straw” in her decision to leave or “run away” from China.

Ms Ren is a Monash University student who has completed her course online for nearly two years because of Australia’s COVID-19 border restrictions. She has booked a flight in August to Melbourne for her last semester.

And she wanted to assist more Chinese girls and women to “run away” by providing a free consultation which used to charge 30 RMB (about AUD$6.3) per hour.

“We cannot see any hope at all,” she said. “We (women) cannot get any support from either legislation or media.” She refers to brief news published by the Chinese news account Beijing Headlines on Weibo - a Twitter-like Chinese social media platform. The post used “conversation” to describe sexual harassment. And it used “confrontation” to describe the male group’s unilateral aggressive assault on the women.

She refers to brief news published by the Chinese news account Beijing Headlines on Weibo - a Twitter-like Chinese social media platform. The post used “conversation” to describe sexual harassment. And it used “confrontation” to describe the male group’s unilateral aggressive assault on the women.

Jiaqi Ren said she felt lucky because she had the choice to come to Australia. Source: Jiaqi Ren

The official statement released no information about the female victim in the hospital except to say “the injured woman being in a stable condition.”

Ms Ren added a Chinese character 润 as a tag to the post. Its literal meaning is “to moisten” but spells as “run” in the Chinese phonetic alphabet. The character became the symbol for the act of running away by migrating overseas. She said while living or working overseas was popular before the assault, it had become more intense due to her and her friends’ experiences of sexual harassment and violence.

She said while living or working overseas was popular before the assault, it had become more intense due to her and her friends’ experiences of sexual harassment and violence.

Jiaqi Ren posted her free consultation ad on Red. Source: Jiaqi Ren

“People started to do real things for it, language tests, [applying for] visas, etc.,” she said.

Shanghai lockdown provoked online searching for “run”

“Run” or “run philosophy” emerged as a new trend on Chinese social media.

In addition to the mounting concerns for female safety, the rigorous “zero-COVID” policy was another reason for the boom in the “run philosophy”, especially during the harsh Shanghai lockdown from April to June this year, when “run” related keyword search rate skyrocketed.

The overall search index for immigration rose a staggering 440 per cent on April 3, according to WeChat‘s WeChat Index following an announcement by China’s officials that they would “…strictly adhere to the zero-COVID policy through the whole society without wavering.” The soar in search hits directly led Baidu -- the biggest search engine in China to hide the searching data related to key words “Yimin”(migration) or “Chuguo Yimin”(immigration) in the Baidu index in April.

The soar in search hits directly led Baidu -- the biggest search engine in China to hide the searching data related to key words “Yimin”(migration) or “Chuguo Yimin”(immigration) in the Baidu index in April.

WeChat Index showed a rapid increase in searching migration. Source: SBS

“I didn’t see any hope in the three years of the pandemic,” April Bai* said.

During the Shanghai lockdown, the megacity's 15 million-strong population was not allowed to leave their apartments and faced severe food shortages, a scarcity of medical resources, and other complications including a lethal mental health crisis, a more challenging environment for vulnerable people, and abuse of power. Although the two-month lockdown was eventually lifted, for Ms Bai, the fear and anxiety of reverting back were compounded by the fact that the partial lockdown remained in place.

Although the two-month lockdown was eventually lifted, for Ms Bai, the fear and anxiety of reverting back were compounded by the fact that the partial lockdown remained in place.

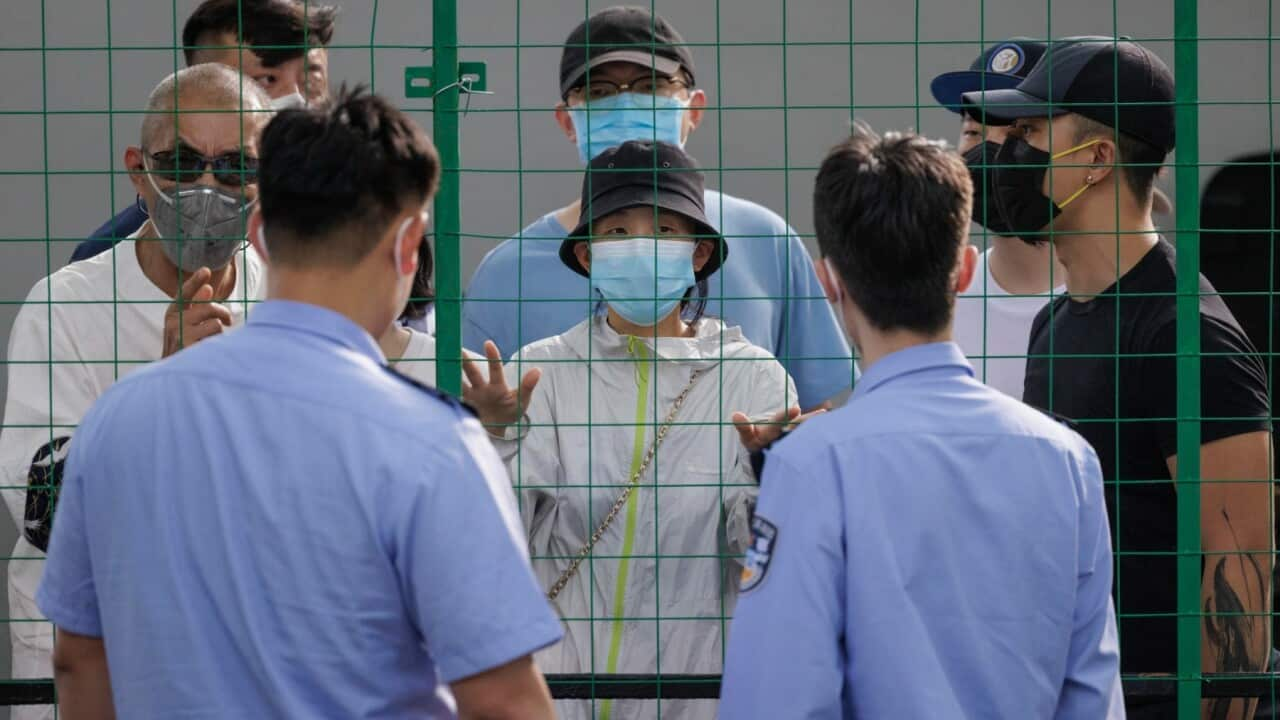

People argue with police behind quarantine fence during the protest, amid new round of COVID-19 lockdowns, in Shanghai, China, 06 June 2022 Source: AAP Image/EPA/ALEX PLAVEVSKI

Ms Bai owns an Internet business in China.

She told SBS Mandarin that she had been ready to pay or do whatever it took to “run” to Australia after she witnessed the extreme lockdown in Shanghai.

Simon Chen, a migration consultant from NewStars Education and Migration who focused on Australia, said he had seen a significant increase in consultations from Chinese people wishing to leave the country.

Furthermore, “…people from Shanghai accounted for almost a half,” he said. Mr Chen explained that potential migrants from Shanghai tended to be an elite group with a strong economic capacity, which meant they could migrate to Australia through investment immigration.

Mr Chen explained that potential migrants from Shanghai tended to be an elite group with a strong economic capacity, which meant they could migrate to Australia through investment immigration.

A health worker walks past quarantined houses in Shanghai, China on 19 March 2022. Source: Credit: AAP

In order to “run” successfully, Ms Bai said she had drawn up multiple plans, including skilled immigration as well as investigation immigration.

She said she wouldn't give up on her plans even if none of them worked.

“I don’t rule out the possibility of [running away] by student visa,” she said.

The overwhelming stress from all aspects

Ms Bai said she wasn’t completely wedded to the idea of “running away” because China was “her home,” but that lately, the urge had become more pressing.

She said she believed that the tough zero-COVID policy harmed China’s economic development, and the impact had already extended to individuals.

“I can’t just be a well-fed person. I need everything on a higher, spiritual, political level to pursue,” Ms Bai said.

For her and many others, she said Shanghai is only a trigger for leaving, and the high pressure of Chinese society placed a total siege on personal lives.

“It’s impossible to receive a work message from your Australia boss at 2 am,” Wenmiao Xin, a Chinese fashion photographer based in Melbourne, said. She said she was looking for a path to become a permanent resident in Australia. She expressed her rejection of the 996 working hour system, which stands for requiring employees to work from 9 am to 9 pm, six days per week, which was the unwritten rule applied in many technology companies in China.

She expressed her rejection of the 996 working hour system, which stands for requiring employees to work from 9 am to 9 pm, six days per week, which was the unwritten rule applied in many technology companies in China.

Wenmiao Xin's fashion photography expressed the suppressed environment Chinese women were facing by writing two Chinese characters on models' faces. Source: Wenmiao Xin

“Involution” was the word mentioned by all the ready-to-run interviewees spoken to by SBS Mandarin.

This was a sociology concept where intense internal competition did not result in productivity or improved innovation. And the opinion of China was troubled with involutional spread on social media, where people discussed faced excessive working hours, unusually high housing prices, workplace sexism, and age discrimination.

Lexi Jia successfully broke through the barriers to leaving Shanghai and arrived in Sydney in April this year. She said she wished to bring her little sister, a year seven girl, to Australia.

“She cannot finish her homework until 11 pm every night and no rest on weekends,” said Ms Jia, a high school teacher in NSW. “I want her to live the way she wants and enjoy her life. I don’t want her to experience the fiercer competition.”

The biggest worry for Ms Bai was uncertainty about China’s entry and exit policy, as well as the migration policy. “Whether it is foreign trade or normal immigration, [the policies] are increasingly strict,” she said.

People who decide to move under the “run” wave will still face difficulties, although Australia’s 2022-23 budget has forecast 30,000 places above 2021-22 planning levels.

Ms Ren said she wasn’t sure how to access permanent residency in Australia after she graduated but that she believed leaving China was the first and the correct move.

*Name changed to protect the person’s identity.