Nearly half the world’s languages will have disappeared by the end of this century, says a UNESCO report. The organisation has designated 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Language -to raise awareness of that fact.

But, another crucial component of language and how we record information may also be at global risk: alphabets.

The alphabets, scripts and writing systems we use to encode and record language gather less attention than the spoken languages themselves, but researcher Timothy Brookes says their disappearance would be a tragedy for human civilization.

As president of Endangered Alphabets, which catalogues the world’s endangered scripts in an online atlas, Brookes became interested in the world’s languages when he began carving them into wood.

“It actually began ten years ago when I started carving words in wood, and I started carving wood into signs for people to hang up, a member of my family to hang up outside their businesses or whatever.”

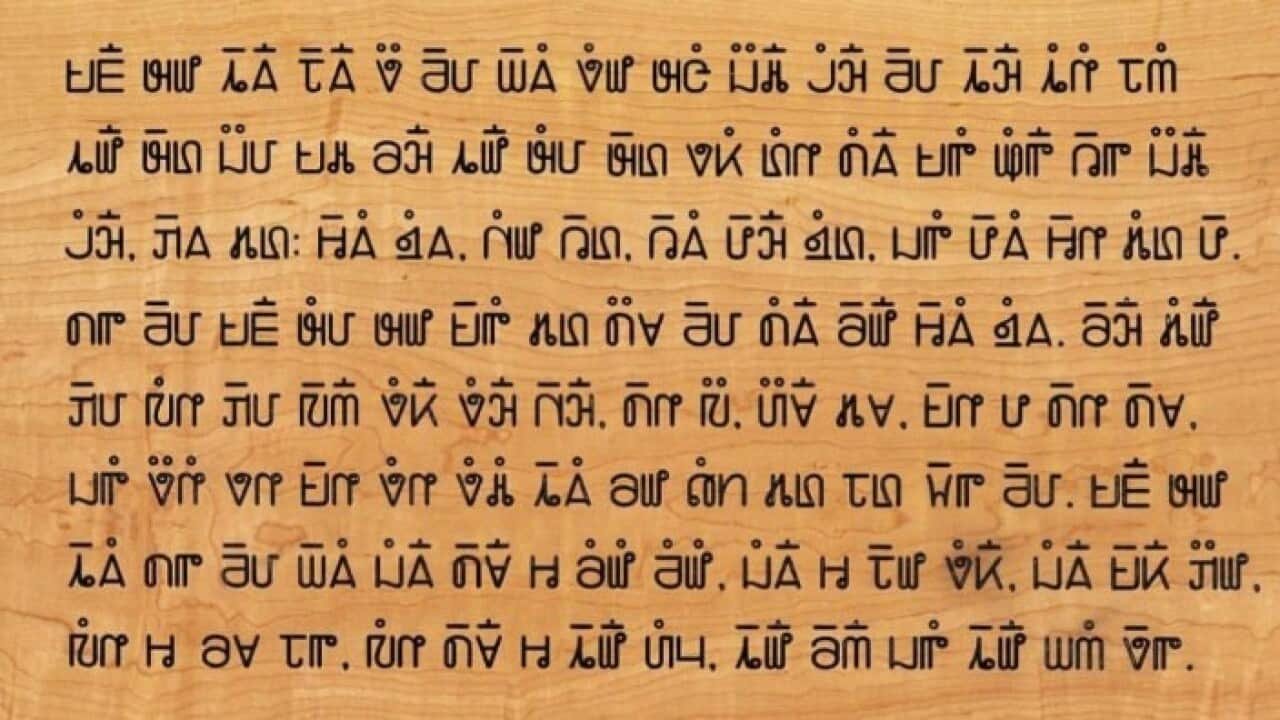

Some of the scripts and alphabets of the world that are at risk of disappearing, says Timothy Brookes, Endangered Alphabets Source: Endangered Alphabets

While UNESCO has done intensive research into the loss of indigenous languages, little information was gathered about endangered alphabets, so Brookes created the Endangered Alphabets initiative. Listing more than 100 alphabets deemed likely to be endangered, his tells a brief story about each language and where it is in the world.

According to Brookes’ research, there are around 170 alphabets in the world and nearly 80 percent of them are endangered. He says that most native languages in countries such as the US and Australia, where English is the language of the dominant culture, are extinct, and other dominant cultures risk the extinction of other languages and alphabets unless proper care is taken.

Online atlas of endangered alphabets that world's minorities and indigenous people are trying to preserve and revive their languages and scripts, Timothy Brookes, Endangered Alphabets Source: Endangered Alphabets

“If a country has a dominant culture and that country has its minorities and Indigenous communities who also have their languages and cultures, then either their cultures or languages will be endangered,” says Brookes.In some instances, particulary in the case of the Hmong language and alphabet, says Brookes, people have been targeted and killed for seeking to preserve or improve their communities' language or writing system.''

“He created a writing system that his people adopted, taught and used as a piece of cultural dignity and self-respect that was immediately seen as a threat to the dominant and colonial culture,” says Brookes of Shong’s achievement and death.

"Phahauh Hmong, the writing system he created has also been banned in some of the Southeast Asia countries like Laos and Vietnam," says, Timothy Brookes, founder of the Endangered Alphabets.

Shong Lue Yang was a spiritual leader of the Hmong people in the twentieth century who helped to develop and record an alphabet — the Phahauh script — for their language that was previously only spoken. Known as the for his work, he was assassinated in 1971 in Laos shortly after he published the alphabet.

Brookes says rather than being a peripheral issue, such losses of language and cultural identity around the world contribute to major public health crisis and must be taken more seriously by governments.

“When a minority or indigenous culture loses it sense of identity and purpose, then suicide rates go up, alcoholism and drug uses goes up, child mortality goes up, education rate goes down, birth rate goes down,” says Brookes. “It’s not only a collective and personal loss, it is also a public health crisis and you see this crisis in Canada, it happened in the United states I believe it happened in Australia.”

Learn more about why Phahauh Hmong was imprinted into a stone plate with other languages in Australia in Hmong here:

A spirit of inclusion and appreciation on the importance of those languages on the part of the dominant will also affect whether alphabets survive, Brookes says.

“If you openly celebrate and embrace diversity, then you are likely to promote those individual cultures, their musics — all those aspects,” says Brookes. “It really comes down to the dominant culture’s attitude toward minority cultures.”

The tide is turning around the world, though, says Brookes, who cites government initiatives as having an effect on the preservation of indigenous languages and alphabets.

Awareness and appreciation of Indigenous language is growing in Australia, while New Zealand even broadcasts some major programs in Maori.

The Filipino government has also recently “introduced a bill to identify native languages, writing systems and set policies to protect, preserve, promote them and use whatever means to disseminate and to teach these languages in the education system,” says Brookes.

Meanwhile the Japanese government also recently recognized its Ainu Indigenous culture by introducing new laws to protect and preserve its native heritage.

Another example he cites is of Canadian road signs “that are also written in both English and in Inuktitut, the Canadian Innu’s script.”

“So all these incidents are a pretty encouraging sign,” says Brookes.