After China banned imports of most plastic waste in 2018, developing countries, particularly in South East Asia, have received a huge influx of contaminated and mixed plastic waste that are proving difficult or even impossible to recycle.

In Indonesia, the port city of Surabaya in East Java and Batam in the Riau Islands are two destinations for waste shipments. Australia is one of the exporting countries, but the waste arriving is poorly controlled and potentially dangerous for those processing it.

"Scrap paper imported from Australia was contaminated with garbage including plastic bottles, used lubricants and scrap electronics," , head of the customs department at the Tanjung Perak port in Surabaya.

Meanwhile that as many as 49 containers containing waste and plastic waste were found in Batu Ampar port in Batam and would be exported back to their home countries, such as Australia, France, Germany, Hong Kong and the United States. Thirty eight of the 49 containers contained hazardous and toxic materials, usually referred to as 'B3', based on customs inspection laboratory results. The that Australian company Visy Recycling was behind the export of a container of plastic waste regarded as toxic found in Batam. It is reported a document stated the container was sent by one of the world's biggest recycling companies and marked as "non-B3", containing mixed non-toxic plastic scrap, but the container stank and leaked black sludge with visible maggots.

The that Australian company Visy Recycling was behind the export of a container of plastic waste regarded as toxic found in Batam. It is reported a document stated the container was sent by one of the world's biggest recycling companies and marked as "non-B3", containing mixed non-toxic plastic scrap, but the container stank and leaked black sludge with visible maggots.

Indonesian officials check one of the 49 containers loaded with a combination of garbage, plastic waste and hazardous materials in the city of Batam. Source: ANDARU/AFP/Getty Images

Why import waste?

Amid the debate on the issue of contaminated waste, a fundamental question arises as to why developing countries, including Indonesia, still want to receive waste from developed ones.

Riko Kurniawan, Director of the Forum for the Environment in Riau, Riau Islands asks just that question.

"Why is there still a policy of accepting imported waste while our regions have not yet had the capability or technology to manage or recycle this waste?," he tells SBS Indonesian.

Riko says that while imported waste is reputedly used for production materials, this is not always true in reality.

"Many are dumped in garbage dumps that are not managed properly," he says. "If we import 100 per cent of the waste, what they manage is 20 to 30 per cent [of the waste recycled] at most. The rest becomes a regional burden."

Riko says that in Indonesia the waste business is of great value, not just because of the value of the waste itself, but because of payments received from the exporters simply to receive it. He argues that this is why waste imports continue, even though domestic waste management has not yet reached a high standard.

"So from the calculation of the business, they [the importer] get money to manage waste," he says. "Coupled with the results from the processing of the imported waste, they receive two profits."

Imported waste is welcomed by developing countries because it talks money, says the Director of Forum for Environment in Riau Islands. Source: ANDARU/AFP/Getty Images

What is Australia's role in Indonesia's waste business?

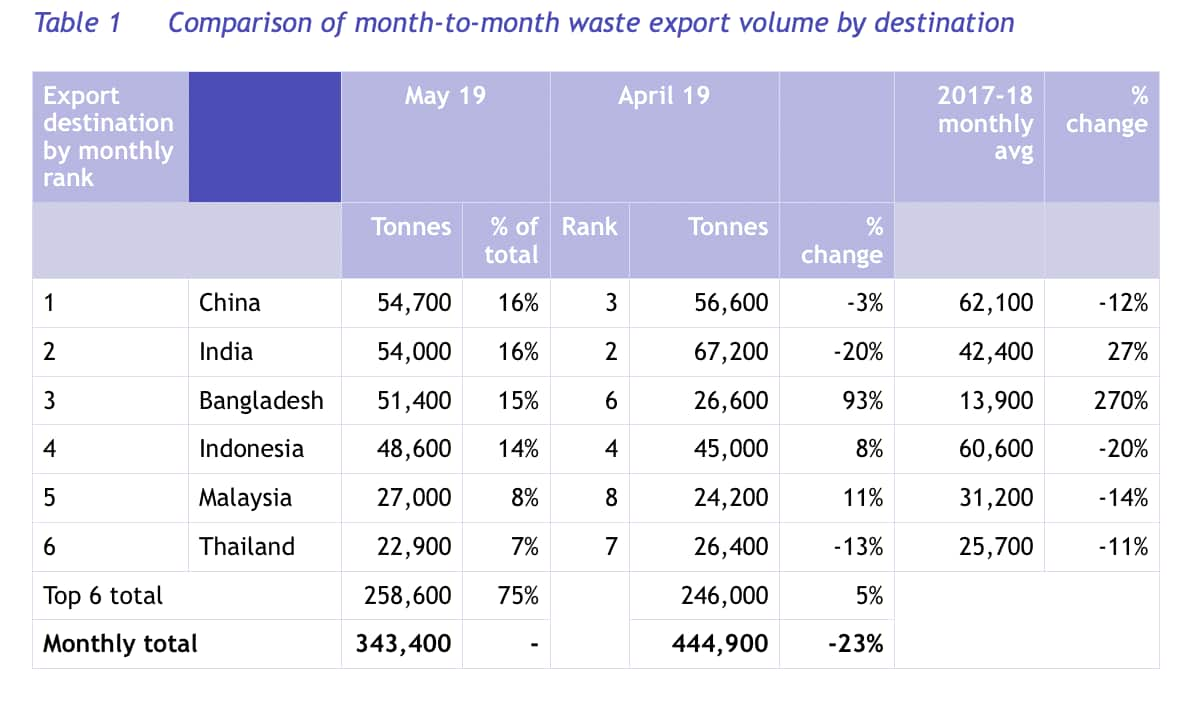

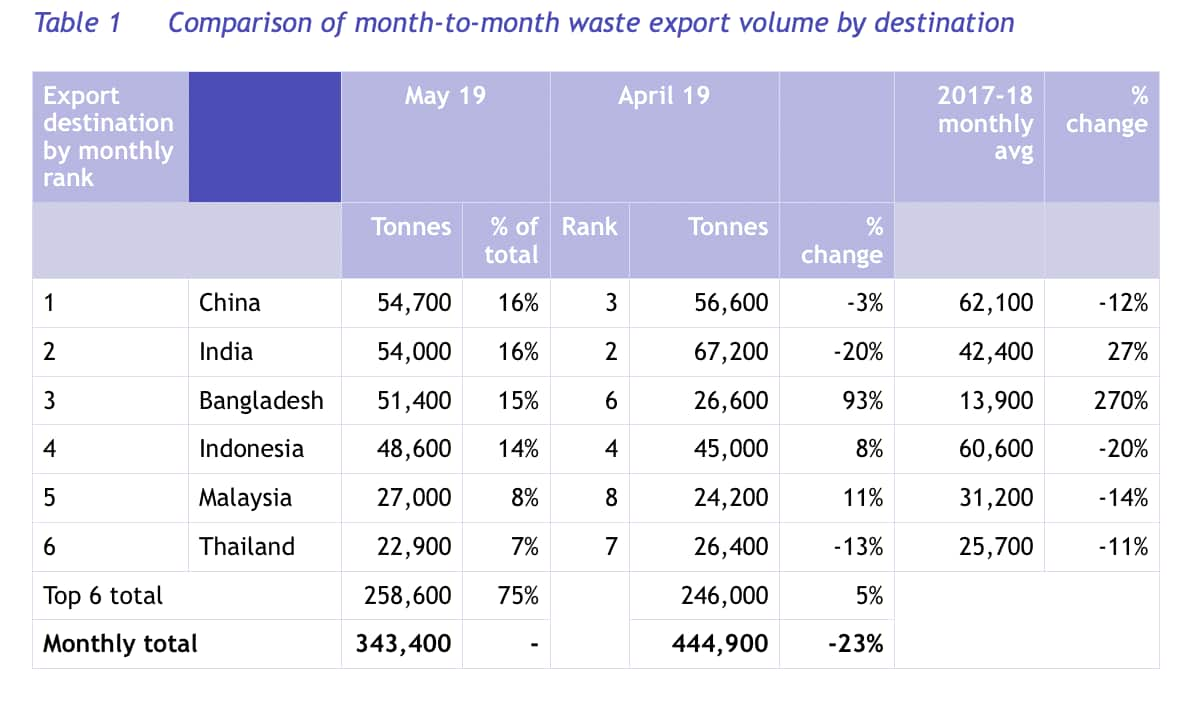

Based on data reported by Blue Environment, an organisation commissioned by Indonesia's Department of the Environment and Energy to analyse and report on Australian waste exports, there are six countries receiving 75 per cent of Australia’s waste exports as of May 2019. They are China (including Hong Kong and Macau), India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The waste exports to Indonesia were dominated by scrap metals. The data also says that Australian exports of hazardous waste decreased by three per cent in May, with the largest fraction being old tyres, followed by lead waste and scrap. But compared to monthly average for 2017-18, exports of scrap plastics and hazardous wastes in May 2019 were considerably higher.

The data also says that Australian exports of hazardous waste decreased by three per cent in May, with the largest fraction being old tyres, followed by lead waste and scrap. But compared to monthly average for 2017-18, exports of scrap plastics and hazardous wastes in May 2019 were considerably higher.

Blue Environment assessment of waste exports from Australia in May 2019 (Blue Environment) Source: Blue Environment

While a new policy of waste import restriction has been implemented in Indonesia, the data shows that it has not yet impacted the Australian waste export business.

Assessment of waste exports from Australia in May 2019 (Blue Environment) Source: Blue Environment

Return to sender?

Responding to the issue of imported contaminated garbage, the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) together with related parties says it will send the waste back to the countries of origin.

The Port of Tanjung Perak customs in Surabaya eight containers containing 282 garbage bundles weighing 210 tonnes to Australia, which are considered contaminated to the B3 standard. This garbage arrived at Tanjung Perak on 12 June, and was sent by the company PT MDI through Shipper Oceanic Multitrading from the Port of Brisbane, Australia.

Basuki Suryanto, head of the customs department at the Tanjung Perak port, says that the department will ask importer company to re-export or send the waste back to Australia, no later than 90 days from entering Indonesia.

But Riko Kurniawan, Director of the Forum for the Environment in Riau says that even though the government orders this return, there will be obstacles in its implementation.

"The policy is good, but it will take more cost to return them," he says. "And there will be another obstacle if the country of origin refuses to accept it."

How to stop the import of illegal trash?

In order to prevent illegal shipments of garbage from occurring and entering the country, Riko says that the Indonesian government must change its policy.

"The government must revoke policies on waste, including the licensing, so the policies of Indonesia and the regions are to no longer accept imported waste," he says. "Our country is also a waste producer anyway."

Riko adds that even though it is agreed globally that B3 waste must be processed in the country of origin and not be disposed of in other countries, the implementation is not easy.

"Who can supervise it [the entry of B3] if the import policy is still there?," he asks. "The policy must be revoked first and revised again. The permits of waste importation must be regulated again and no more foreign waste.

"The main problem is that the countries producing excessive waste shift the burden of its management to developing countries. Unfortunately, this is welcomed by developing countries because money talks."