Valentina Caputo has been helping to look after the children of frontline healthcare workers since the start of the pandemic while they fight COVID-19.

“We look after the children of people who work in hospitals, and we also look after the children of researchers who are currently working on a vaccine for COVID-19.”

"My colleagues and I have been very proud to be able to make a small contribution in our own way,” says Ms Caputo, who works at a childcare centre close to the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Highlights

- Ms Caputo has been living in Australia for eight years and has spent $60,000 for a Bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood Teaching

- She is not eligible for Jobkeeper or any other financial assistance from the government because of her visa status

- She was partially stood down as childcare attendance dropped during Melbourne’s Stage 4 lockdown restrictions

However, since the start of Melbourne’s Stage 4 lockdown restrictions, her work arrangement has drastically changed because of attendance at the centre dropping significantly and she now works only two days a week instead of three.

"Our centre has between 80 and 85 children normally, but [a day after Stage 4 restrictions] there were only ten children attending because many parents did not qualify as permitted workers,” explains Ms Caputo.

From 6 August, only children of “permitted workers” are allowed to attend childcare. During the first coronavirus lockdown April this year, the federal government announced a childcare relief package, which included financial support for early childhood centres and their employees through Jobkeeper wage subsidy when the childcare service was made free for families.

During the first coronavirus lockdown April this year, the federal government announced a childcare relief package, which included financial support for early childhood centres and their employees through Jobkeeper wage subsidy when the childcare service was made free for families.

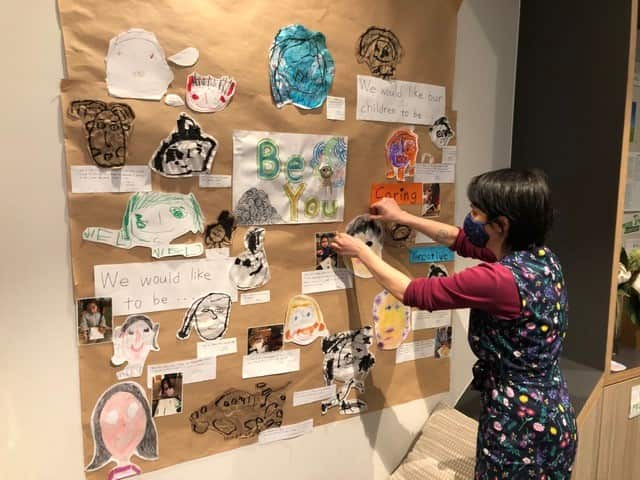

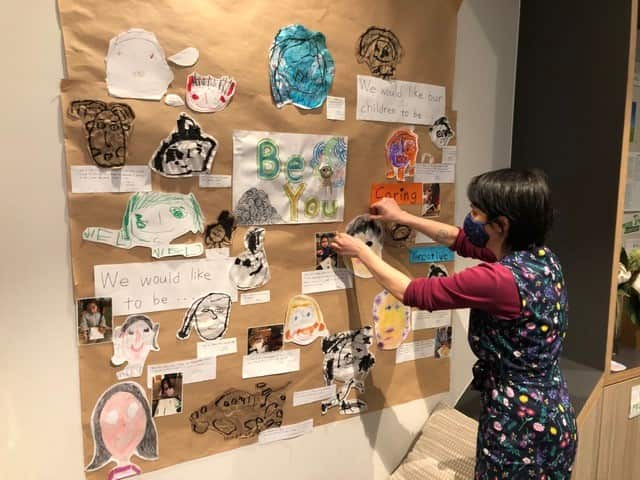

Valentina Caputo in classe Source: Courtesy of Valentina Caputo

But in July, the measures were reversed and Jobkeeper was no longer available for the childcare sector.

According to Kate Noble, an Education Policy Fellow at Victoria University’s Mitchell Institute, Ms Caputo's situation is representative of the issues the childcare sector is facing during the pandemic.

“There is a really high level of casual workers in the sector, and anyone who had been employed for less than 12 months was not eligible for Jobkeeper so that was one of the explanations that were used to withdraw Jobkeeper and replace it with a transition payment and what the government is calling an 'employment guarantee'."

She says the new arrangement doesn’t offer a strong level of protection to casual childcare workers.

"[The employment guarantee] requires workers and kindergartens to maintain the position but there is no guarantee that for example hours won’t be cut significantly. So, you could have a casual worker whose job is guaranteed if their employer is accessing government subsidies but their hours could be cut and that obviously has a significant impact on child educators' livelihoods,” says Ms Noble.

Being a temporary resident, Ms Caputo has no access to any government subsidy.

"I have been angry for a long time, especially with the government, because I have never felt I was enough [here]; I have studied, I have always been contributing to society and I am in a job that is apparently considered essential but I never feel regarded as part of this society."

‘Invisible to society’

For the first four months of the pandemic, Ms Caputo and her husband were able to draw money from their superannuation, but with the second lockdown in Melbourne, the situation for her has become untenable.

So, after eight years in Australia, she has decided to move back to Italy with her husband and their nine-year-old and five-month-old daughters.

"We asked ourselves a thousand questions... if this was the society we wanted to be part of after all the sacrifices we've made. We pay taxes like citizens or permanent residents but we have nothing in return, neither Medicare nor Childcare Benefit.”

According to Siobhán Hannan, a veteran of the early childhood education industry of over 20 years, the problem is structural and endemic to the sector.

"Jobkeeper, even when it was granted to workers, was not enough because many of the people working in the sector are not permanent residents in Australia or do not have stable jobs, but at least it guaranteed a basic income.

“Now that the funds are given to the childcare centres, the operators are not forced to give money to workers or to guarantee hours of work. So, if there are no children, the workers are sent home. These workers are invisible to society.”

Mitchell Institute’s Kate Noble says the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the precariousness and low wages in the sector to the surface.

“COVID-19 has really exposed a whole lot of very serious problems with the way our sector operates: early childhood educators are not well paid, there are high levels of casual employees in the sector and low levels of job security.”

"For childhood educators, the uncertainty of working conditions has also been added to the fear for their own health, given the impossibility of maintaining coronavirus protection measures at work," she says.

A spokesperson for the Federal Department of Education said the government will pay approximately $2 billion in childcare subsidy this quarter to eligible families.

"In addition to the CCS, the Government will pay child care services a Transition Payment of 25 per cent of their fee revenue during the relief package reference period (17 February to 1 March) from 13 July until 27 September, rising to 30 per cent for services in Melbourne because of the Victorian lockdown.

The spokesperson said the Transition Payment is paid instead of JobKeeper to support early childhood educators and employers.

"In accepting Transition Payments, providers must offer an Employment Guarantee by continuing to employ those employees who were working or being paid JobKeeper Payment at the end of the Relief Package.

"Standing down permanent staff without pay is inconsistent with the Employment Guarantee," he said.

Metropolitan Melbourne residents are subject to Stage 4 restrictions and must comply with a curfew between the hours of 8pm and 5am. During the curfew, people in Melbourne can only leave their house for work, and essential health, care or safety reasons.

Between 5am and 8pm, people in Melbourne can leave the home for exercise, to shop for necessary goods and services, for work, for health care, or to care for a sick or elderly relative. The full list of restrictions can be found here. All Victorians must wear a face covering when they leave home, no matter where they live.

People in Australia must stay at least 1.5 metres away from others. Check your state’s restrictions on gathering limits.

If you are experiencing cold or flu symptoms, stay home and arrange a test by calling your doctor or contact the Coronavirus Health Information Hotline on 1800 020 080. News and information is available in 63 languages at