Highlights

- John Corea, who arrived in Australia by ship in 1876, was 'probably' the first Korean in Australia, according to Associate Professor Jay Song

- New research at the University of Melbourne sheds light on early Korean immigration to Australia in the 19th century

- John died in 1924, aged 65

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of SBS Korean.

In the process of our latest research on Korean migration to Australia, funded by the Australian Research Council, our team at the University of Melbourne discovered John Corea, a man who landed in South Australia on a ship called the Lochiel in 1876.

While we don’t have the passenger list for the Lochiel, we do know that it was a tea trading ship that operated between Shanghai, China and Australia.

We also don’t know John’s original Korean name but in his naturalisation record from 1894 (see below), John was noted as a “native of Corea” aged 35 years, working as a shearer and living in Gol Gol, a tiny town in far-west New South Wales.

The country name “Corea” became “Korea” during Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), the rumour being so that Japan would come before Korea alphabetically. For anyone who has conducted research on the global history of Korean migration and diasporas, this was a ground-breaking historical finding.

For anyone who has conducted research on the global history of Korean migration and diasporas, this was a ground-breaking historical finding.

John Corea's certificate of naturalisation. Source: Supplied/Jay Song

At the same time, I had to make sure that John Corea was from Korea, and not from Corea, Italy.

To better understand John's journey, I had to piece together what was known about other early Asian migrant labourers. This took me on a three-week academic road trip of 4,000 km through the Australian outback.

I drove from Melbourne to Sydney, from Sydney to Gol Gol in NSW and Mildura in Victoria across the Murray River, from Wentworth to Broken Hill, and back to Melbourne via Bendigo.

During my road trip, I interviewed two dozen small business owners, migrant workers, historians specialised in early Chinese and Japanese migrants, archivists and members of local historical societies. Trying to retrace John’s steps, I learned so much about pre-federation Australia, the outback, the lives of early Asian migrants in the 19th century and their close engagement with local economies in shearing, mining, pearl diving and paddle boats up and down the Murray River.

Trying to retrace John’s steps, I learned so much about pre-federation Australia, the outback, the lives of early Asian migrants in the 19th century and their close engagement with local economies in shearing, mining, pearl diving and paddle boats up and down the Murray River.

Jay Song (right) with the Wentworth Historical Society Source: Supplied

Some were highly successful in integrating to Australian society by marrying European women. Others, like John Corea, struggled to survive when the White Australia policy kicked in.

John became naturalised in 1894. Before that, he’d already tried a Mineral Release in Silverton near Broken Hill in 1879 and was awaiting it to be executed until 1889.

One year after his naturalisation in 1895, he applied for a mining licence in Coolgardie in West Australia. When the warden, Percy Fielding, inquired about John’s application, the then Undersecretary Miners replied 'no' on the basis that his “naturalisation in N. S. Wales [does] not apply here” in WA - an instance of parochialism instead of racism. John didn’t give up. He went to White Cliffs in outback NSW to try his luck and finally had his mining licence in 1903.

John didn’t give up. He went to White Cliffs in outback NSW to try his luck and finally had his mining licence in 1903.

Source: Supplied/Jay Song

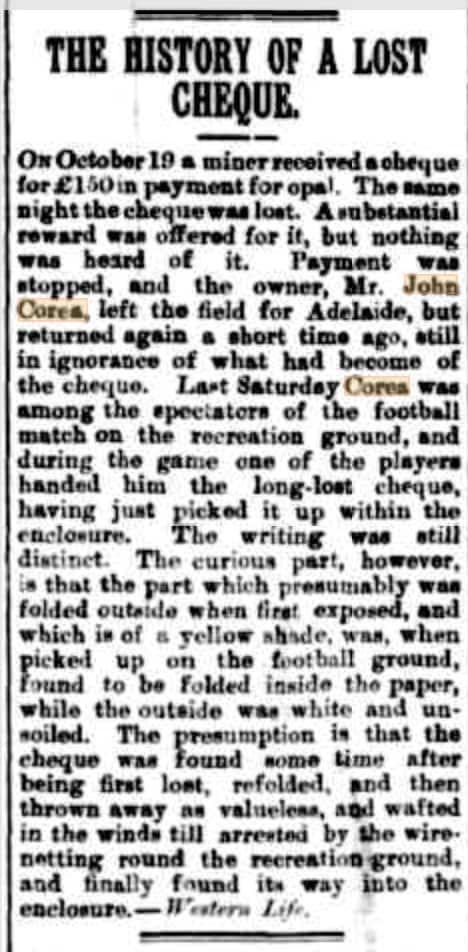

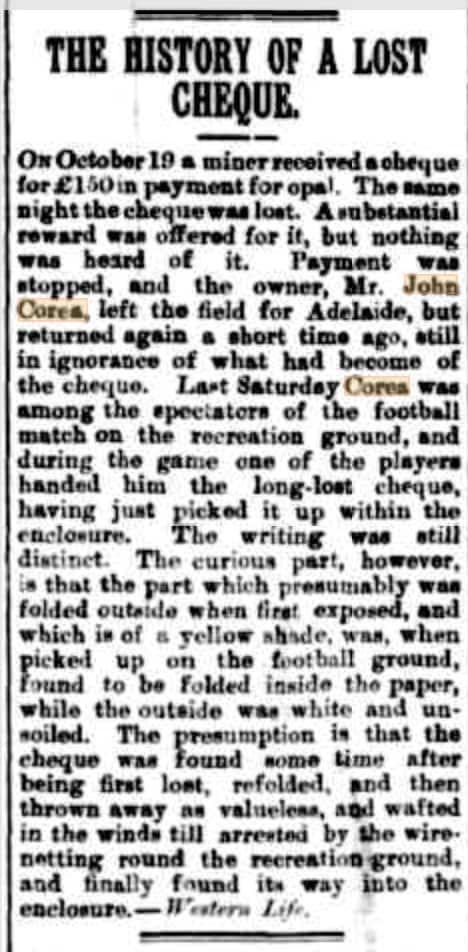

John must have earned quite a bit from mining. In 1902, his name appeared in a local newspaper, Barrier Miners, titled “The History of a Lost Cheque”. Apparently, John lost the cheque, worth 150 pounds, while watching a football match with his mates. He later found it lying on the ground. John later contracted tuberculosis, probably from poor working conditions in mines, and was hospitalised in Adelaide.

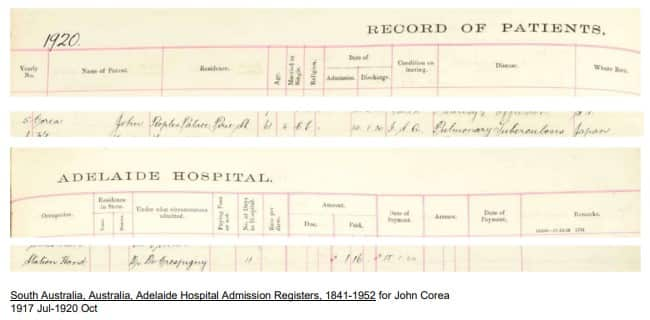

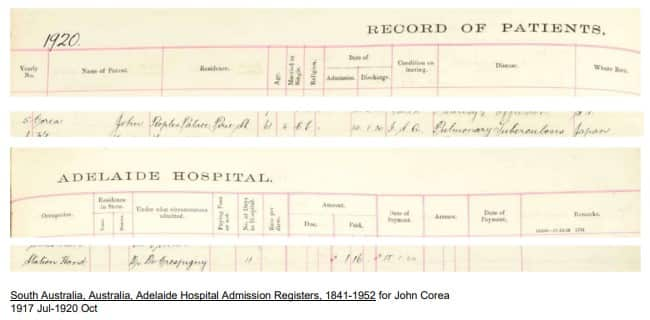

John later contracted tuberculosis, probably from poor working conditions in mines, and was hospitalised in Adelaide.

'The History of a Lost Cheque' (1902, June 12). Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW: 1888-1954), p. 3. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from nla.gov.au/nla.news-art Source: Supplied/Jay Song

He stayed in the People’s Palace which was run by the Salvation Army to provide affordable accommodation for workers. In the hospital records, John’s place of birth was noted as “Japan”.

As Korea lost its sovereignty in 1910 and was under Japanese colonial rule until the end of the Second World War, it’s only natural that John’s birthplace was left as Japan, instead of Korea. This seems to confirm that John Corea was indeed from Korea. John died in 1924, aged 65, having never married and leaving no children. His funeral was executed by Evelyn and Richard Robertson, who placed an advertisement for it in a local newspaper on 6 August 1924.

John died in 1924, aged 65, having never married and leaving no children. His funeral was executed by Evelyn and Richard Robertson, who placed an advertisement for it in a local newspaper on 6 August 1924.

John Corea's Adelaide Hospital admission register. Source: Supplied/Jay Song

He’s buried in Nicole’s Point Cemetery in Mildura, lot number F40. I went to his grave. There's nothing there. No headstone. Probably no visitors in the last hundred years. I offered him a bowl of rice, kimchi and seaweed. I couldn’t find soju, a Korean liquor, so instead poured a bottle of Coopers instead. I hope he didn’t mind. John led me to a better understanding of early Asian migrant labourers in the Australian outback, not only the better-known Chinese miners in Victoria and NSW or Japanese pearl divers in Queensland and WA, but also the numerous unrecorded and forgotten young men.

John led me to a better understanding of early Asian migrant labourers in the Australian outback, not only the better-known Chinese miners in Victoria and NSW or Japanese pearl divers in Queensland and WA, but also the numerous unrecorded and forgotten young men.

John Corea’s gravesite at Nichols Point Cemetery, Mildura. Source: Supplied

We don’t know how John came to Australia, via which routes from Korea. He was only 17 years old when he landed here in 1876.

His deceased assets included a nickel watch and savings of 425 pounds, including the war bond. Unfortunately, I haven’t found any photo of John but I can only imagine what he would have looked like from his fellow Asian Australians in the late 19th century.

Unfortunately, I haven’t found any photo of John but I can only imagine what he would have looked like from his fellow Asian Australians in the late 19th century.

John Corea’s last will: New South Wales State Archives.Deceased Estates Index 1880-1956 (Pre A 010007 [20/1008]) Index number 15 Source: Supplied/Jay Song

Below is a photo of John Egge, who came from Shanghai, married an English woman, had 10 children (seven survived), and became a highly successful paddle boat captain in Wentworth, NSW. If John had had surviving children, we would have many Coreas in Australia today. His body is gone but his spirit of dreaming, challenging and local friendship survives.

If John had had surviving children, we would have many Coreas in Australia today. His body is gone but his spirit of dreaming, challenging and local friendship survives.

John Egge (1830-1901) in Wentworth, New South Wales. Source: Supplied by Jay Song (Wentworth Historical Society)

Remembering John Corea, probably the first Korean in Australia. Rest in peace, John.

Jay Song is an associate professor of Korean studies at the University of Melbourne, where she is the director of the Korean Studies Research Hub. Her research into Korean migration to Australia is funded by the Australian Research Council. She gives special thanks to thank Rosemary Bruce-Mullins and Louise Spencer for their research assistance.