51-year-old Kyoko Kawasaki is a Japanese lecturer at the University of Western Australia.

She has been running a storytelling group for children of Japanese background in her spare time for the past 12 years.

“We read books in Japanese and speak in Japanese and children play in Japanese. I receive a lot of things from children. They give me joy. When I read books, it’s not just for the children, I also read the books, I receive joy from children’s books.”

There are over 300 community languages spoken in Australian households. Yet, the number of people who spoke only English at home has risen by more than 500,000 since 2011.

Japanese is the most popular language commonly taught in Australian schools, followed by Italian, Indonesian, French, German and Mandarin.

From her experience of running the Japanese storytelling group, Kawasaki notices that once bilingual children start school, their interest in speaking in their native tongue tends to drop.

“And it also depends on the interest of children if they are really interested in some sports, they lose time to mix with Japanese friends, they lose time to use Japanese and their interest shifts from Japanese stories and friends and families to other things - especially for a family with family member who doesn't speak Japanese it is a big challenge to keep the children’s language at home.”

72-year-old Wen Jie Zhou moved to Melbourne ten years ago after retiring as a school principal in China.

“My husband is a doctor. He goes to work every day. I had nothing to do at home and felt very bored.”

Back then, as a newly arrived retiree in Melbourne, Zhou felt like a fish out of water with a lifelong of professional experience as an educator but no student to put her skills to use.

“We’ve always been educators, always been teaching. When I suddenly found myself without students, I felt a bit lost - especially coming to a foreign land. Yes, we could eat and drink and enjoy pleasant sceneries, it was quite nice, but I feel o this was wasting life. First of all, I pondered how we could find our joy in the old age of our lives? I needed to find other opportunities.”

An opportunity came up in 2010 when Zhou, along with other older speakers of Mandarin, Spanish and German were invited to participate in a Monash University research project, which connected older migrants with senior high school students learning a second language.

Dr Hui Huang was the chief coordinator of the Chinese component of the program.

“Many people speak a language other than English at home. However, on the other hand, we got kind of second language learning report that, in fact, there is a kind of the language crisis in schools so the ideas then jump up, say, why we don't combine community resources to complement language curriculum?”

This initiative was particularly useful for students who didn’t have the cultural background to practice the language they were learning at home.

“Because the initial idea of this project was to facilitate the language practice in a kind of authentic way which in fact was evidenced in our project. We found that students improved very significantly in their confidence in the daily conversation with the native speakers of the language they learnt.”

Mandarin is the second most spoken language at Australian homes after English. It is also one of the most commonly spoken languages in the world followed by Spanish and Arabic.

However, research shows that only five per cent of secondary students who study the language last right through to year 12.

Zhou recalls her initial attempt of conversing with a student in Mandarin when neither of them could hardly speak each other’s language.

“So, I asked her what kind of outdoor activities do you like? She didn't know how to answer my question so she gestured the cycling movement. I understood what she meant. So, I drew a picture of a bike. She said ‘yes!’ and gave me a hug. It was quite interesting.”

The research outcomes were compiled into a book co-edited by Dr Huang titled “Rethinking second language learning: using intergenerational community resources”.

She says the project found mutual benefits for both the older and younger participants beyond language education. “We also noticed that older immigrants got a lot of benefits from program. For example they feel they become younger and fresh.”

This was especially true for the Chinese seniors involved in the project. Dr Huang says many felt isolated and disengaged from the community.

By sharing their language skills with the students, they were able to find meaning and a sense of belonging to Australia.

Zhou was involved throughout the three-year project tutoring several students.

“Suddenly I felt my life is enriched. It’s no longer just about eating, drinking and hanging out. I realised that I can still fully utilise my professional skills in some way. I found that my life has become a lot more relaxing and joyful. I’ve also found more confidence in settling in a foreign country.”

Do you think the Punjabi community of Australia should also adopt this model? Tell us what you think by emailing us on [email protected]

SBS is celebrating a love of learning languages in Australia in our SBS National Languages Competition from 15 October to 18 November. For the first time, this year’s competition is open to Australians of all ages who are learning a language, including those learning English. To find out more, visit sbs.com.au/nlc18 .

More from SBS Punjabi

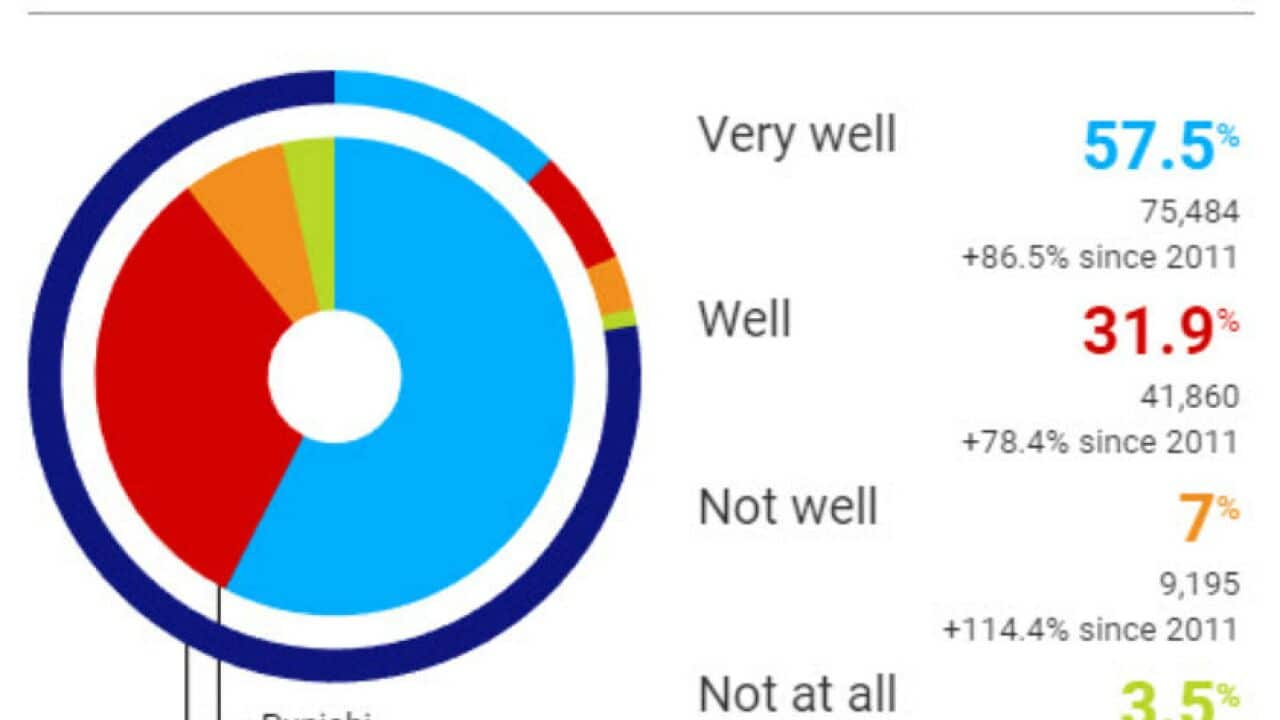

Census 2016: Presenting a profile of the Punjabi community in Australia