Highlights

- ‘Red Closet: The hidden history of gay oppression in the USSR’ will hit Australian bookstores in May.

- Former Russian president Boris Yeltsin decriminalised homosexuality in 1993 to become accepted by the West, but homophobia continues in Russia.

- Up to 1000 gay men were jailed every year in the former USSR under the law banning homosexuality.

In 1993, a group of activists arrived at a penal colony on the outskirts of St Petersburg.

Their goal was to demand the release of several gay men, who had been imprisoned there under the Soviet regime’s so-called “sodomy” law.

Several months earlier, the then-Russian president Boris Yeltsin had changed the law by decriminalising homosexuality and repealing the already existing sentences.

“I don’t care about any law changes. They were behind bars, and they are all staying behind bars,” yelled the director of the colony at the activists.

Article 121.1 of the Soviet Penal Code was introduced by the former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. It punished homosexual relationships between men with up to five years in prison.

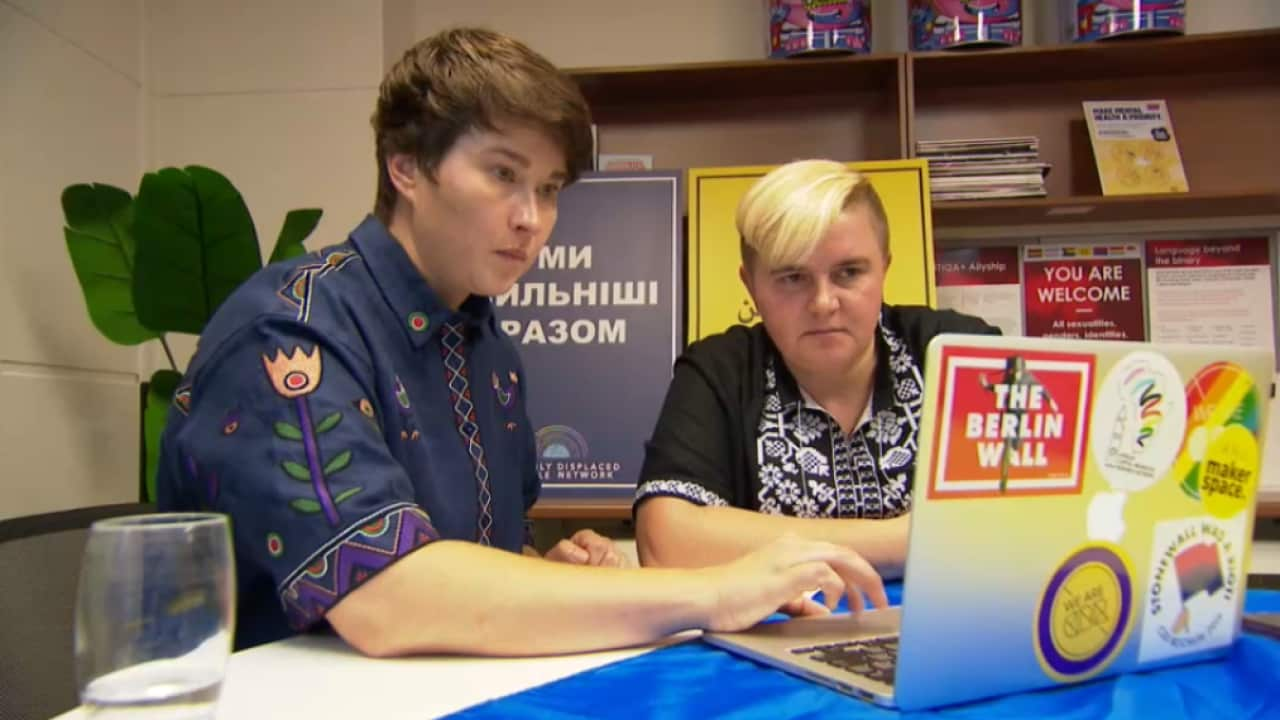

Sydney-based writer and researcher Rustam Alexander has published a telling account of the excesses faced by homosexual men in the erstwhile USSR.

Life far from gay for homosexuals in the USSR

In conversation with SBS Russian, Mr Alexander unveils the striking events in the lives of the USSR’s incarcerated gay men.

His upcoming book titled Red Closet: The hidden history of gay oppression in the USSR will hit Australia’s bookstores in May.

The Russian way of dealing with gay rights is brutal and horrible.

"It’s important to see how it unfolded in the Soviet Union,” he says.

"My book is not just some dry progression towards ‘a better future for gays’. These are unique and fascinating stories of people who tried to survive in a place that was oppressing them."

Between 1934 and 1993, tens of thousands of Soviet men were imprisoned for being gay.

However, when the law was changed in 1993, it was up to LGBTIQ+ activists to contact almost 800 prisons across Russia and demand the release of convicted gay men.

The Russian government was never interested in releasing all convicted men.

According to Mr Alexander, President Yeltsin decriminalised homosexuality just to become accepted by the West. But in Russia, homophobia and discrimination remained.

Activists led by now-famous journalist Masha Gessen have documented the names of all gay men considered to be in prison.

As Mx Gessen recalled in an interview with , their main task was to “send telegrams to each facility to find out whether the men were still incarcerated”.

Occasionally, a prison staff member would agree to go through all the personal files looking for a particular name. Sometimes, this would lead to a couple of people being released.

Rustam Alexander explains that with the fall of the USSR, life of queer people in Russia improved, mostly on paper.

In reality, Russia carried its Soviet homophobic legacy into the future.

“Queer people in new Russia were still excluded from decision-making and their fate was still decided by heterosexual politicians, usually homophobes,” he adds.

Working under a pseudonym, Mr Alexander believes that uncovering the history of gay oppression in the USSR is a vital step in fighting for the rights of LGBTIQ+ community in Russia. For this reason, back in 2013 he started his PhD research into the issue while at the University of Melbourne.

He spent months going through online and offline archives in the countries of the post-Soviet region.

Based on the thesis, he later published an academic book .

But he felt it was necessary to bring the discussion beyond academic circles.

I wanted to tell the story of gay oppression in the USSR to a wider audience.

“I wanted to tell these stories to a reader who might not necessarily be interested in gender studies or social concepts, but who simply wants to know what happened. Just like myself 10 years ago,” he tells SBS Russian.

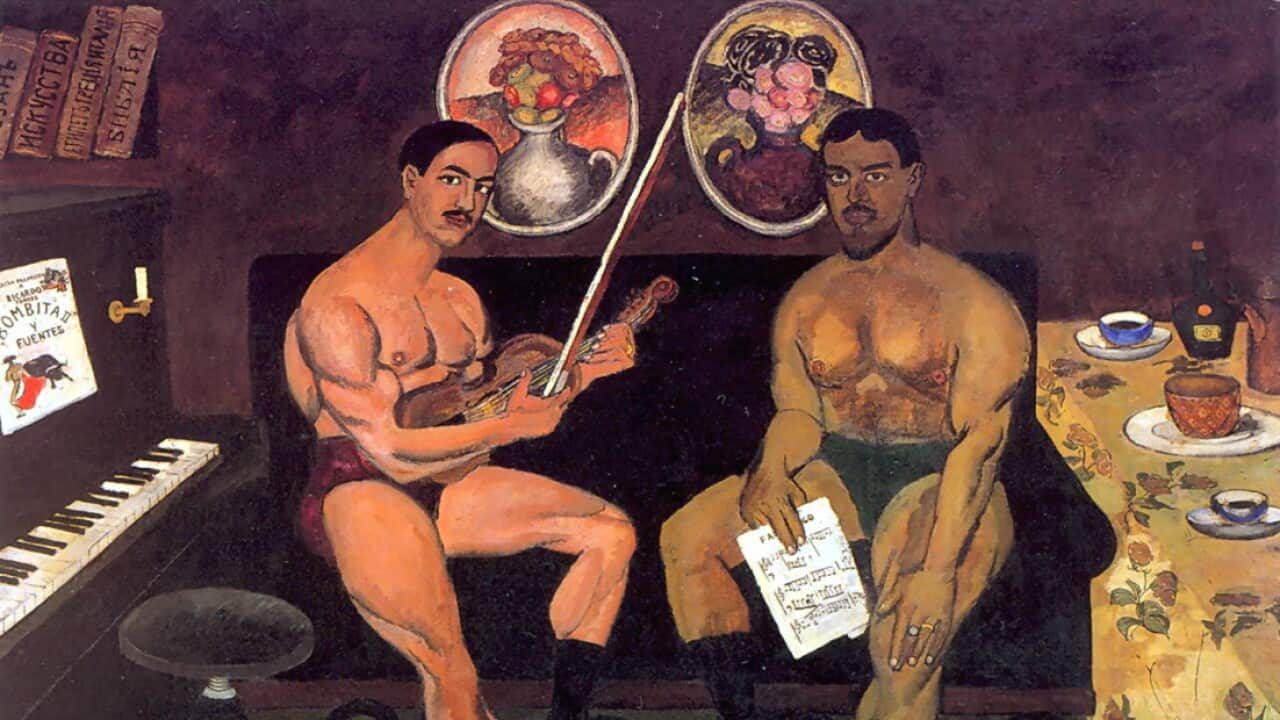

'The Boys start running out from water' aka 'Lunch Break in the Donbass' by Alexander Deineka (1899-1969) circa 1935 displayed at State Latvian Museum, Riga. Credit: Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty

Gay propaganda next door to Kremlin

Rustam Alexander identifies as a gay man.

Having grown up in post-Soviet Russia and with the freedoms that Moscow had to offer in the 1990s and early 2000s, he used to distance himself from the issue of the oppression of Russia’s queer community.

In 2013 at a club in Moscow, an Australian expat asked Mr Alexander why he wouldn’t conduct research into the history of gay oppression in Russia.

At that time, Russian president Vladimir Putin had just signed a homophobic law banning the so-called “gay propaganda” amongst minors.

Mr Alexander was surprised by the suggestion.

“Why would I? Is this even interesting to anyone?” he recalls his initial reaction.

“Just like many other gay men in Moscow and Russia in general, I haven’t always been vocal about LGBTIQ+ rights. It has been a long learning journey, says Mr Alexander.

I used to be one of those people wondering why we even need Pride.

Over the past 10 years, he has come to realise that the issue of gay rights is an issue of human rights.

For that, Mr Alexander thanks Australia.

Living in Australia gave me a fresh perspective on the LGBTIQ+ issues.

“Here in Australia, I liberated my mind and realised that it is a valid subject for scientific research.

“It’s not some ‘scandalous’ subject. It’s an important issue that has a direct bearing on LGBTIQ+ people in Russia today,” he adds.

Ironically, the club where it all started for Mr Alexander in 2013, is called Propaganda.

A cafe by day and club by night, Propaganda is Moscow’s iconic institution with the most popular weekly gay nights.

The location of this club is equally interesting — at walking distance to Kremlin as well as State Duma, the Russian Parliament, and around the corner from FSB (formerly known as KGB) headquarters.

“I have seen a lot of familiar faces from Russian TV screens at Propaganda at those Sunday gay nights,” recalls Mr Alexander.

“There are a lot of queer people in the Russian media and amongst the decision makers. This could be a huge force. But many of them choose to lead a double life instead,” he remarks.

In 2021, Mr Alexander was hopeful that popularising stories of Soviet gay men might help move the discussion about the rights of queer people forward.

For this reason, he accepted an offer from a publishing house to .

It appeared in Russia’s bookstores in November 2022, days before President Putin signed amendments to the 2013 anti-gay law, now effectively banning any mention of LGBTIQ+ anywhere in public.

This made Rustam Alexander’s book illegal.

However, he says, he found support from Russian independent online magazines and podcasts.

“All of the 5000 copies of the Russian version of Red Closet were sold. But the publisher cannot take further risks and print more. It’s just too dangerous,” Mr Alexander explains.

In January, in the wake of a new wave of persecution and the anti-gay law, the publisher, Individuum Books decided to sell one of its branches, Popcorn Books which specialised in young adult fiction.

While the amendments to the “gay propaganda” law were introduced in Russia, word spread on national TV and pro-government Telegram channels about a novel published by Popcorn Books.

The novel about the romance of teenage boys Summer in a Pioneer Tie, was .

Bookstores around Russia started taking the novel off the shelves.

Pro-government activists in Khabarovsk went further and bought all copies of the novel and put them through a paper recycling machine.

, a pro-government activist is seen ripping the book apart and saying, “our country will be cleared of this disgusting propaganda that is aiming to destroy a thousand-year-old Russian civilisation”.

'Hot Blooded' film poster by artist Anatoly Belskiy. Credit: Mosfilm / Kinorium

Hidden in the archives

Queer people were taboo in Soviet society and finding mentions of them required time and persistence.

Based in Melbourne for pursuing his PhD, Mr Alexander spent a lot of time flying back and forth to Europe and studying state archives in Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine and Russia, formerly member states of the USSR.

Scientific research papers, medical reports, minutes of court hearings, educational brochures — Mr Alexander would study all kinds of documents hoping to find clues.

He was also faced with bureaucratic barriers.

“In Russia, you have to wait for 75 years for some documents to be declassified. I will only be able to access some documents from the Brezhnev era around 2030,” he says.

In the former USSR, it was only illegal for two men to have a relationship, there was no law banning lesbian relationships.

However, in the archives, Mr Alexander found numerous examples of researchers or government officials trying to push for a law banning homosexual relationships between women as well.

“The Soviet Union was a lot like today’s Russia,” he weighs in, adding it has "career politicians in a homophobic country advocating for stricter anti-gay laws.”

“In Russia today, these are parliamentarians like Yelena Mizulina or Alexander Khinshtein who continuously abuse the issue just for the sake of their own political gains,” Mr Alexander adds.

In an infamous speech given before a parliamentary committee in October 2022, Mr Khinshtein referred to an episode from the popular cartoon show, Peppa Pig, which featured Penny the Polar Bear with two mothers.

Mr Khinstein described the cartoon show as part of a “hybrid war against Russia,” and called LGBTIQ+ issues a “weapon of the hybrid war”.

“In the Soviet Union decades ago, there were other similar ‘Khinsteins’ advocating against lesbian women, just because they knew that in a homophobic country, it might help them go up the career ladder,” Mr Alexander adds.

Mr Alexander says that while studying the archives and reading notes from court hearings, he could see how citizens were using the anti-gay law to blackmail, threaten and ruin each other’s lives.

He refers to a story of KGB lieutenant Aleksei Petrenko that he found in Ukraine’s state archives.

Mr Alexander tells SBS Russian that Mr Petrenko was living a comfortable life in Kharkiv but was said to be an abuser who beat his wife.

Eventually, he was about to lose his party membership and job. Hoping to fix that, Mr Petrenko decided to stage arrests of his male lovers.

“Mr Petrenko scheduled a date with his lover at their usual cruising spot. At the same time, he bribed some teenager to appear there instead of him,” he narrates.

“He was supposed to show up with the police and arrest the lover for alleged ‘sodomy’,” he adds.

However, the policemen ended up arresting not only the lover, but also Mr Petrenko, who was later tried in court for being homosexual and received a prison sentence.

Mr Alexander believes that uncovering stories like that of Mr Petrenko can help in understanding the scope and intensity with which the former Soviet Union was shaping the countries that were once part of it.

“The Russian and the Soviet experience shaped many other countries, and in particular, homophobia in them.

"It’s important to understand where all this homophobia comes from,” he adds.

Guests at a 1921 wedding organised by Afanasy Shaur, a prominent figure in the St Petersubrg queer community. All male guests are seen wearing drag. Credit: Courtesy of Central State Archive, St Petersburg www.spbarchives.ru/cga

Harry Whyte writes to Stalin

There was a brief moment when gay men could live freely and were not persecuted in the USSR.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, the new Soviet government abrogated the old legal code.

That included decriminalising homosexuality, banned in the Russian Empire.

In the Red Closet, Rustam Alexander tells the story of a gay man Harry Whyte.

Mr Whyte moved to Moscow from Scotland in the early 1930s inspired by socialist ideals, the revolution and the fact that homosexuality was not illegal in the USSR.

In Moscow, he started working as an editor in an English-language newspaper and dating a man, whom Mr Alexander refers to in his book as Ivan.

Mr Whyte was not aware that Stalin was already in discussions with his inner circle about re-criminalising homosexuality.

Stalin was convinced that homosexual relationships between men were “a weapon of the Imperialist West”.

The law banning homosexuality was signed in 1934 and around the same time, Mr Whyte’s boyfriend, Ivan, disappeared.

Ivan’s sister told Mr Whyte while in tears that “you are the problem; he was taken because of people like you”.

Mr Whyte tried talking to his boss and even to the secret police, but his attempts to find any traces of Ivan were unsuccessful.

Eventually, he decided to write to Stalin directly asking him to stop the persecution of homosexual men.

“I love this story because it’s a great example of a clash between two opposing worlds,” remarks Mr Alexander, adding that it was a collision between “the idealism of a Western man and, well, Joseph Stalin”.

Stalin received and read Whyte’s letter.

However, instead of responding to him, he only signed it off to the state archive with a note that stated: “Idiot and a degenerate”.

Soon after that, fearing persecution, Mr Whyte left the Soviet Union and went back home to Scotland.

Rustam Alexander believes that stories like the one about Mr Whyte or Mr Petrenko serve to remind us of Russia’s brutal history going on in parallel with the fight towards better rights for the LGBTIQ+ community in the West.