As Mabo Day is marked around the country on Wednesday, some say progress towards reconciliation between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples has stalled over the past 28 years.

The day commemorates Torres Strait Islander Eddie Koiki Mabo and his role in the High Court decision on 3 June 1992 which overturned the terra nullius declaration - that Australia was once land belonging to no-one. It allowed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have rights to their land.

According to the , there have been 496 native title determinations since.

"Mabo was an incredible landmark decision within Australia," said Jamie Lowe, the CEO of the National Native Title Council.

But Mr Lowe, a Gunditjmara Djabwurrung man, said the native title process is a hard undertaking for Indigenous groups. "You speak to anyone that's been in a native title determination, it's tough for the people. It's traumatic, bringing up a lot of old stuff. Usually, it takes the best part of a decade to go through the courts," he told SBS News.

"You speak to anyone that's been in a native title determination, it's tough for the people. It's traumatic, bringing up a lot of old stuff. Usually, it takes the best part of a decade to go through the courts," he told SBS News.

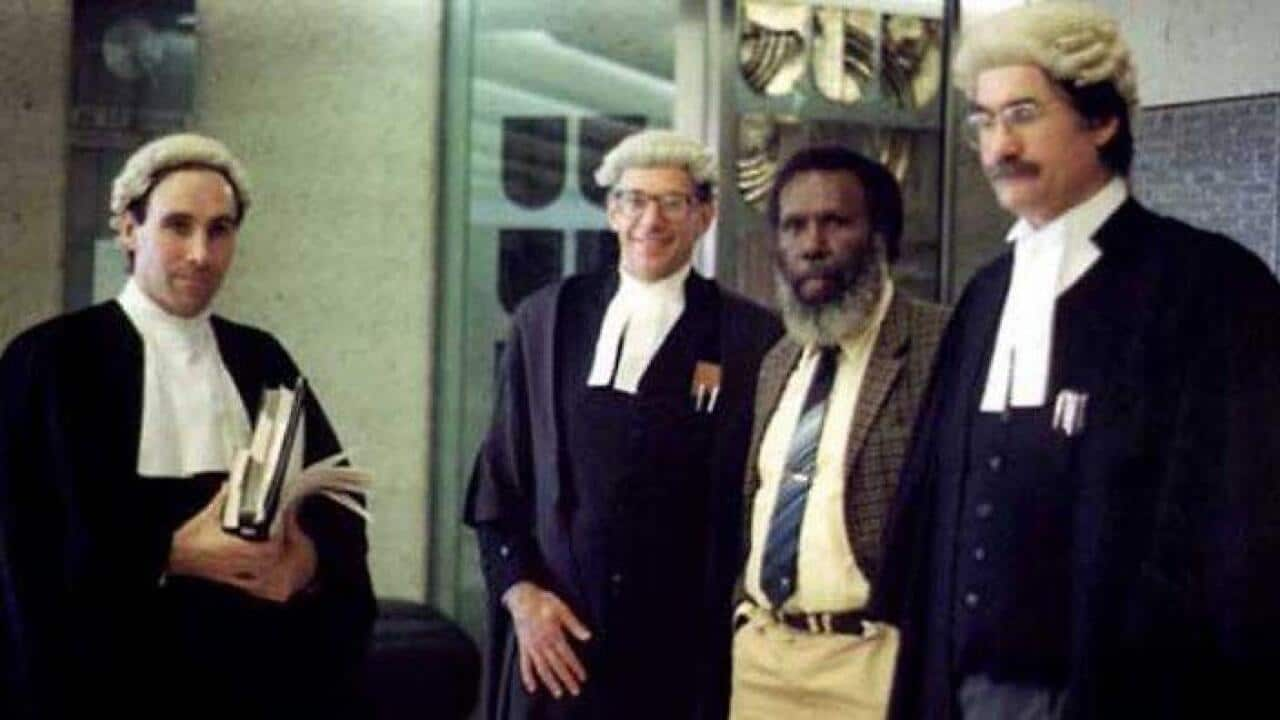

Eddie Mabo. Source: SBS

Only certain types of land can be subject to determinations and people need to prove they have a continuous connection to that area.

Mr Lowe said he will use Mabo Day this year as a chance to reflect on how important was, but how few moments there have been like it since.

"Close to 30 years down the track, the progress has been stagnant ... There is a lot of unfinished business," he said. "We've had small wins here and there, but they are few and far between."

He said the faltering discussion around treaties at a federal level was perhaps the most disappointing. Some states and territories have moved towards treaties, but the federal government remains firmly opposed.

"The situations that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people find themselves in - going to prison, going hungry, overcrowded houses ... To really make progress and make change, we need to reconcile with our Indigenous people though treaty-making."

'Some amazing stories'

Patricia Lane was the first registrar of the National Native Title Tribunal from 1994-1997 and is now a barrister and senior lecturer at the University of Sydney. She said the 28 years since the Mabo decision turned out differently than some expected.

"The industry groups thought that this would be the end of the world as pastoralists and miners would lose the ability to carry on their economic enterprise - that hasn't panned out as they thought," she said.

"Indigenous people thought this may be a new era of recognition of their rights - that also hasn't panned out as they thought. "[But] Indigenous people are getting back, to the extent possible, control over their country and the ability to use the resources of their country.

"[But] Indigenous people are getting back, to the extent possible, control over their country and the ability to use the resources of their country.

Eddie Mabo's grave on Mer Island in the Torres Strait. Source: AAP

"There have been some amazing stories of people being able to get enterprises up and successfully combine economic development with continuing to care for their country and being connected with it."

But Ms Lane said state governments had often been a roadblock in further progress on native title.

"What's probably held things back a bit is state governments haven't really been prepared to negotiate more broadly ... They all put up particular barriers," she said.

"Obviously in resource states like Western Australia there's a big concern around minerals, in other places like Victoria, there are different concerns. States generally have very nervous attitudes to native title because they fear they are going to lose control of their land systems." Michael Mansell, the chairman of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, took aim at his state government in an interview with SBS News.

Michael Mansell, the chairman of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, took aim at his state government in an interview with SBS News.

Eddie Mabo's case saw the High Court overturn the legal doctrine of terra nullius. Source: NITV

"From 1995 to 2005, less than one per cent of the state was returned ownership to Aboriginal people," he said.

"But since 2005, in that last 15 years, no land has been returned to Aboriginal people at all. Successive Liberal and Labor governments have dropped the ball and they've lost momentum on reconciliation that was established in the 1990s.

"Why isn't the government simply legislating to return land to those Aboriginal people that can't prove the difficult test of native title?"

Material from the federal government's National Indigenous Australians Agency says: "the native title system is complex and continues to change and mature over time, especially as more claims are finalised. Each native title group has their own unique challenges and opportunities".

"The National Indigenous Australians Agency plays a critical role in supporting Indigenous service providers and communities to recognise the rights and interests Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have with their land and waters. A key focus for government is to make sure the system is working well."

Information released on Mabo Day last year said: "37 per cent of all land in Australia now has a recognised native title interest in it. This figure will grow to about 60 per cent once all claims are finalised."