For Axel’s 18th birthday, all he wanted was a ticket out of Venezuela.

It took months to convince his parents but eventually, they bought him a one-way flight from the capital, Caracas, to Miami, where the 20-year-old is now building a life for himself.

“Pretty much none of my friends are in Venezuela anymore, they’re scattered in cities all around the world,” he tells SBS News.

'A new world'

When Axel arrived in the United States he spoke patchy English and only had a few hundred dollars to his name. Now he has a smooth American accent and picks up casual bar and restaurant work to pay the bills.

“It’s like a new world here, and there’s a lot more opportunities, which is amazing,” he says. Axel lives among tens of thousands of Venezuelans who have made the same trip to Miami.

Axel lives among tens of thousands of Venezuelans who have made the same trip to Miami.

Axel at a New York subway station in 2017. Source: Supplied

The Floridian city, a three-and-a-half hour flight from Caracas, is known for its palm trees and waterfront high-rises. For Venezuelans fleeing crime, oppression, and financial stagnation, it is often their first impression of the US, just as it was for hundreds of thousands of Cubans 50 years earlier, in the midst of Fidel Castro’s Cuban revolution.

Back then, a suburb to the west of Downtown Miami was renamed Little Havana, and today, the suburb of Doral, less than two kilometres from the airport, has become known at Little Venezuela.

Source: SBS News

Dividing the nation

In the real Venezuela, the situation is dire. The country has been suffering through an ever-deepening political and economic crisis for five years. Crime has skyrocketed, with the homicide rate in Caracas now estimated to be one of the highest in the world.

Venezuela is divided between the Chavistas – those in favour of the socialist policies of former President Hugo Chavez, now continued by President Nicolas Maduro’s United Socialist Party (PSUV) – and those who want to see an end to socialist rule.

In the past 12 months, human rights groups say the government, which has dodged fresh elections, has become increasingly violent and totalitarian.

More than 100 people – mostly young, male anti-government protesters – were killed during four months of civil unrest earlier this year, according to a tally kept by the Associated Press.

Patricia Andrade, whose organisation Venezuelan Roots collects and delivers donated supplies for new arrivals in Miami, says some parents in Venezuela are sending their children overseas to keep them from the protests.

“The parents say that they needed to come because their sons wanted to stay on the streets protesting and the National Guard almost killed them, or killed one of their friends,” she tells SBS News.

Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, is almost worthless. Food, medical supplies, and other basic necessities are in short supply. The annual inflation rate is expected to rise to more than 2,300 per cent in 2018.

Edixon, a 26-year-old bank-teller working in Caracas, says he thinks about leaving Venezuela every day. Many of his friends have already left and with the chronic inflation, his salary barely covers expenses.

"With the money you earn you buy what you can of food - but nothing else. It’s not enough to buy clothes or medicine or rent," he tells SBS News.

Edixon had to drop out of an accountancy course after the fees became unaffordable. The main reason he hasn’t left Venezuela yet is that he simply doesn’t have the money, he says, but he also doesn’t want to split up his family.

Migration generation

There are no official figures available on Venezuela's migration levels, but Tomás Páez, a Venezuelan sociologist based in Madrid who is running a study into the country’s diaspora, estimates that 2.2 million Venezuelans now live overseas, amounting to at least seven per cent of the population.

“It’s unprecedented in our history, Venezuela has become an emigration country,” Dr Páez tells SBS News.

It wasn't always this way. Venezuela used to be one of Latin America’s richest countries. As Europe suffered through war and turmoil in the early half of the 20th century, the country became a major oil exporter and drew migrants from around the world.

“We received people from Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Colombia, Argentina, Ecuador, Peru, Chile,” Dr Páez says.

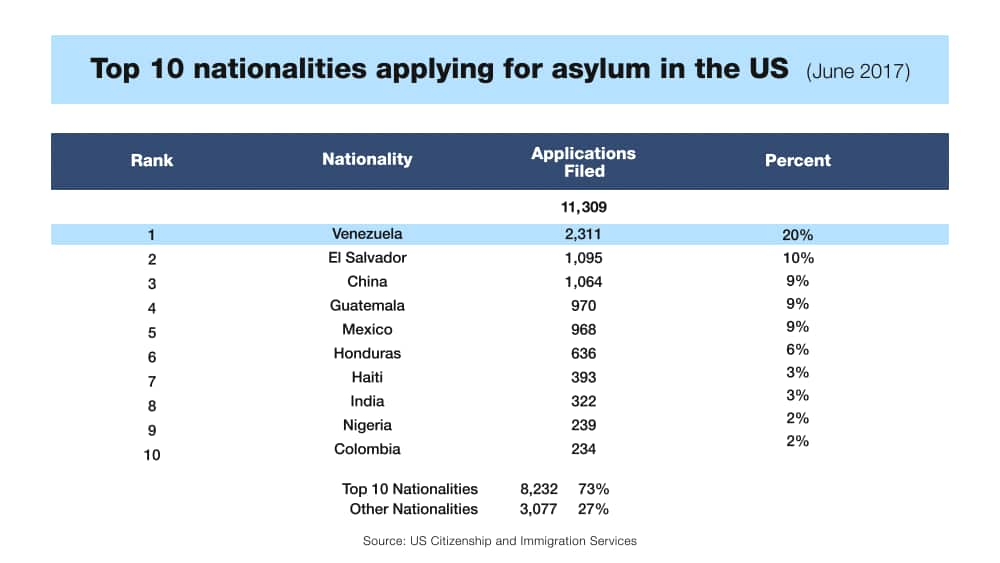

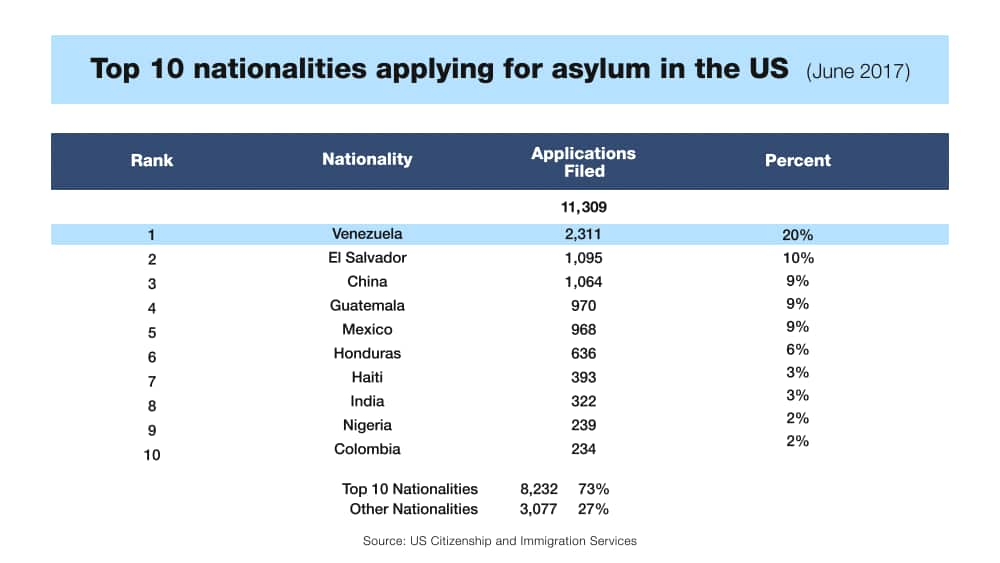

Many of those first and second-generation migrants are among those now leaving. Venezuelans currently outnumber every other nationality in US asylum applications, with up to 3,000 made each month. The Miami office of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service has become the busiest in the country, currently facing a backlog of over 50,000 cases. The UNHCR estimates that 300,000 Venezuelans have also travelled across the border to Colombia, which boasts a comparatively thriving economy.

The Miami office of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service has become the busiest in the country, currently facing a backlog of over 50,000 cases. The UNHCR estimates that 300,000 Venezuelans have also travelled across the border to Colombia, which boasts a comparatively thriving economy.

Source: SBS News

Over 50,000 Venezuelans have also filled out refugee requests around the world this year.

Lack of prospects and hope

The exodus is particularly acute amongst the country's youth, the majority of whom want to leave.

A poll conducted earlier this year by the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas, showed 53 per cent of 18 to 29-year-olds are considering leaving the country – compared with 35 per cent of the general population. In 2014, only 12 per cent of people wanted to go.

Alejandro Velasco, an associate professor at New York University and expert in Latin American politics and culture, says educated young people account for a large proportion of those leaving.

“One of the major reasons is the lack of prospects and the lack of jobs and the lack of confidence that things are going to change; a lack of hope about the future domestically,” Professor Velasco tells SBS News.

“But the other factor is that this latest round of protests and unrest has left a lot of youth dead, or in prison.”

A protester hides behind a wall during protests in Caracas, Venezuela in June 2017. Source: EFE / EPA / MIGUEL GUTIERREZ

'My country is so messed up'

Juan, a 28-year-old from Caracas, now lives in Madrid. He is waiting for the Spanish government to process his refugee application.

“The main reason I left Venezuela is the impossibility of having a normal life. You are always fighting different battles,” he tells SBS News.

Juan says he was robbed three times in his home country – each time at gunpoint.

Like millions of young Venezuelans, Juan came of age in the middle of a revolutionary socialist experiment - led by Chavez and built on the back of massive oil revenues.

Price controls and major social welfare spending brought millions out of poverty and gave them access to healthcare and education, but such policies obscured and exacerbated serious problems within the country’s finances. When oil prices collapsed in late 2014, so did the socialist economy.

The impact has been devastating.

Juan's father, who was diagnosed with prostate cancer, was forced to travel to Europe for treatment – he was lucky he could afford it.

In Venezuela, hospitals ask patients to bring their own medical supplies - from chemotherapy drugs to surgical equipment - and desperate parents often use crowdfunding websites to get lifesaving medicine for their sick children. Juan’s parents remain at home but he and his siblings are opting for a more stable future. He watched his brother move to France and his sister move to Australia before he himself moved to Madrid.

Juan’s parents remain at home but he and his siblings are opting for a more stable future. He watched his brother move to France and his sister move to Australia before he himself moved to Madrid.

Three-year-old Ashley and her mother Oriana at a Caracas hospital in 2016. Ashley’s parents were eating just one meal a day to afford scarce antibiotics. Source: AP

Before that, he spent eight months working and studying English at Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia.

“The problems in Adelaide are so simple; like a kangaroo got loose,” Juan jokes.

“Meanwhile in Venezuela, the struggle is freaking unreal. I cannot understand how my country is so messed up.”

There were 5,460 Venezuelans listed as living in Australia in the 2016 census, up from 1,539 in 2006.

Desperate measures

Professor Velasco says he has been struck by the desperation among the latest wave of migrants, which he saw for himself when he visited the Colombian border earlier this year.

“What you’re seeing now is a much more cross-class emigration wave than you’ve seen before, which suggests something really powerful about the depth and the extent of the crisis,” he says.

“It’s not just wealthy or educated people thinking about longer-term opportunities, it’s also people whose more immediate needs aren't being met.”

With many young people leaving, particularly those who have attended Venezuela’s universities, there is a fear that the country could lose a generation of talent and leadership.

“I don’t think it’s yet a situation of a ‘lost generation’ per se, I think there’s still a sense that a lot of people who left recently would want to return if things turn around,” Professor Velasco says.

“But that hope is fading over time.” Dr Páez says that as the crisis drags on, and expats lay down roots and have families, they become less likely to return home – although he believes the concept of a ‘brain drain’ is outdated.

Dr Páez says that as the crisis drags on, and expats lay down roots and have families, they become less likely to return home – although he believes the concept of a ‘brain drain’ is outdated.

Axel during a trip to Chicago. Source: Supplied

“When they go to the United States or Spain or Italy or Australia, they not only go to give, they receive. They are learning skills and having opportunities and making connections that they wouldn’t otherwise have,” he says.

“We now have 2.2 million Venezuelan ambassadors.”

Juan, who clearly picked up the lingo during his time in Australia, longs to return home.

“Go back? Mate, I can only hope,” he says. “I wish to go back and have my life there, of course I want that.”

Axel in Miami is more ambivalent.

“I’m going to go to college and try to make my life here,” he says. He plans to study in the US and wants to work as a journalist.

“But I’m also open to the idea of one day coming back to help rebuild my country with all that I hope to learn in the United States in the years ahead,” he says.

“No one knows what will happen in the future.”

- Juan, Axel and Edixon did not wish to provide their last names.