KEY POINTS

- Amal Osman, her husband, and their baby daughter have been stuck in Port Sudan for the past week.

- Ms Osman says Australian officials told her she could not return home unless their child has a passport.

- They were due to board a ferry on Wednesday, but by midnight, she was told their names were not on a list of evacuees.

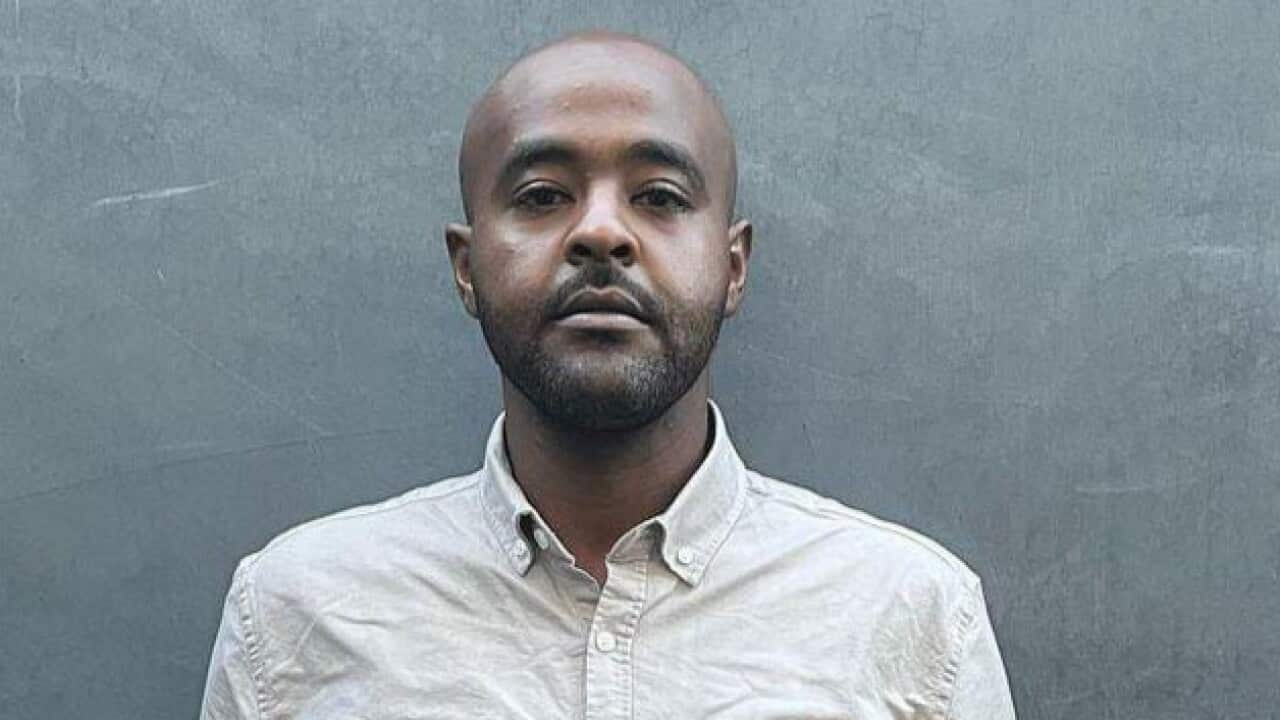

Clutching her eight-month old baby, mobile phone and passports, Australian woman Amal Osman is desperate to make it out of Sudan as an uneasy truce unravels.

More than 200 since , killing at least 500 people and wounding thousands more.

Ms Osman has been stuck in Port Sudan for the past week after escaping the country's capital city Khartoum.

The 28-year-old said she was told by Australian consular staff she could not return home unless paperwork for her daughter's passport was completed before boarding a ferry bound for Saudi Arabia.

"How are we supposed to fill out all this paperwork and access our accounts when there's no cash in the country?" she told the AAP news agency.

Australia does not have an embassy in Khartoum, with the closest in Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

"How can we pull out money (foreign currency) out of thin air?" Ms Osman said.

"I was telling them (consular staff) we are in a crisis. We have left our homes, where do you expect us to get money and stable internet to fill out forms?"

At midday on Wednesday, she was due to board a ferry with her husband and baby Elan, based on advice from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

But by midnight, she was told their names were not on a list of evacuees.

Ms Osman was frustrated at the clarity of information coming from the department.

"When were dropped off to Port Sudan in a bus, we were just left by the kerbside not told where to go or who to contact," she said.

"Hotels were fully booked out and people sleeping everywhere in the lobby."

At the Coral Hotel, which has turned into a makeshift logistical evacuation hub for embassies trying to get citizens out of Sudan, Ms Osman was told to register with United Kingdom and United States authorities.

"They (DFAT) would email different things every day," she said

"One day they're like 'you guys can go to UK' and they say 'you can go to the US'. Everyday it's a different thing but in the end there was never a clear answer."

An armed conflict between the Sudan's military and paramilitary forces broke out in mid-April. Source: AAP, AP / Marwan Ali

Ms Osman criticised the department for not providing humanitarian visas, which were offered when war broke out in Ukraine.

The department has sent a crisis response team and consular staff to Cyprus to help evacuate citizens, with support from Australian Border Force officers.

"This is a similar approach to that taken in response to the Ukraine crisis," a DFAT spokesperson said.

"The Australian government understands the pain and distress the conflict in Sudan is causing to those in Sudan and their families in Australia."

A Sudanese evacuee waits at Port Sudan before boarding a Saudi military ship to Jeddah port on Wednesday. Source: AAP, AP / Amr Nabil

Mona Mohamed was reunited with her husband and children in Cairns a few days ago after a week of travel from Sudan.

She said escaping the war zone without any logistical assistance from the Australian government was a humiliating experience.

"I got three emails, one email telling me the Australian government's ability to assist citizens is severely limited on 21 April, another one asking me about my concerns on 23 April and a third email about how to remain safe," the 50-year-old general practitioner said.

Dr Mohamed tried to contact the Australian embassy in Cairo from Sudan, but it was closed for public holidays and her call went through to voicemail.

It was the same when she made an international call to the DFAT hotline.

"There were no one interacting with us as if we're in a real crisis. They acted as if the war would be stopped and would be something transient," Dr Mohamed said.

After a week in the conflict zone, the Australian permanent resident took matters into her own hands.

She embarked on a treacherous 15-hour bus trip from Khartoum and crossed the border into Egypt, where thousands of refugees have been camped out for weeks.

"It was terrifying, it was a devastating condition to be in suddenly. I kept on making dua' (Islamic prayers) the whole way. We were very scared," Dr Mohamed said.

The uncertainty fuelled her hasty exit from Khartoum.

"If the Australian government had made it clear they were going to help I would have waited," she said.

Dr Mohamed made her way to the Egyptian city of Aswan followed by Cairo and Dubai, before flying to Melbourne and finally to Cairns.

After returning home, she contacted the department to make her feelings known.

"I told them communicating with people via email during a war is nonsense," she said.

"Just call me and tell me how you're going to help. I didn't receive emails because electricity was down."

Dr Mohamed eventually received a reply, but it was more than a week after the conflict erupted, leaving her with questions about Australia's response.

"Why are other countries able to evacuate their residents and their citizens and you cannot?"