Beijing has come under international criticism over its policies in the northwest region of Xinjiang, where as many as one million Uighurs and other mostly Muslim minorities are being held in internment camps, according to a group of experts cited by the UN.

Zohra Imin, a Uighur Muslim based in Sydney, has not spoken to her siblings in two years – and the separation is taking its toll.

“My brothers and sisters – where are they now? Are they inside a camp, prison, dead or alive? I don’t have any information,” she told SBS News. Ms Imin is one of the , now asking questions about the wellbeing of relatives who they’ve abruptly lost contact with.

Ms Imin is one of the , now asking questions about the wellbeing of relatives who they’ve abruptly lost contact with.

“My brothers and sisters – where are they now? Are they inside a camp, prison, dead or alive?”: Zohra Imin. Source: SBS News

“We want to know they are safe and alive. Help us please.”

On Thursday, Chinese authorities were accused of and other Muslims in Xinjiang by labelling "completely lawful" behaviour as suspicious. Human Rights Watch has previously reported that Xinjiang authorities use a mass surveillance system called the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP) to gather information from multiple sources, such as facial-recognition cameras, wifi sniffers, police checkpoints, banking records and home visits.

Human Rights Watch has previously reported that Xinjiang authorities use a mass surveillance system called the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP) to gather information from multiple sources, such as facial-recognition cameras, wifi sniffers, police checkpoints, banking records and home visits.

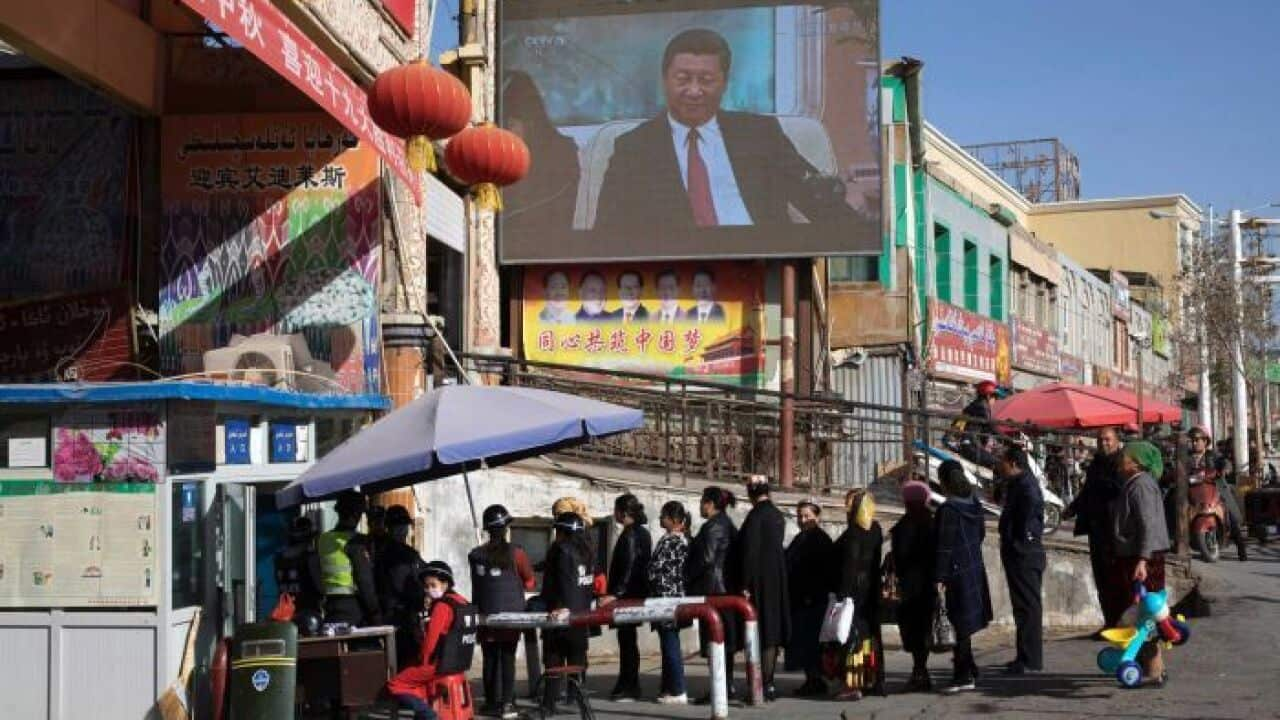

Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar in western China's Xinjiang region. Source: AP

But the new study, entitled "China's Algorithms of Repression", worked with a Berlin-based security company to analyse an app connected to the IJOP, showing specific acts targeted by the system.

Xinjiang authorities closely watch 36 categories of behaviour, including those who do not socialise with neighbours, often avoid using the front door, don't use a smartphone, donate to mosques "enthusiastically", and use an "abnormal" amount of electricity, the group found.

The app also instructs officers to investigate those related to someone who got a new phone number or related to others who left the country and have not returned after 30 days.

"Our research shows, for the first time, that Xinjiang police are using illegally gathered information about people's completely lawful behaviour – and using it against them," said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch.

"The Chinese government is monitoring every aspect of people's lives in Xinjiang, picking out those it mistrusts and subjecting them to extra scrutiny." “China is willing to discuss human rights issues with others, on the basis of equality and mutual respect,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang said on Monday, dismissing claims counter-terrorism measures in Xinjiang went too far.

“China is willing to discuss human rights issues with others, on the basis of equality and mutual respect,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang said on Monday, dismissing claims counter-terrorism measures in Xinjiang went too far.

“We want to know they are safe, and alive. Help us please.” Source: SBS News

“But we strongly oppose others using human rights as an excuse to interfere with China’s internal affairs.” The treatment of Uighurs is an issue the Chinese government would prefer to keep out of the spotlight – long maintaining the camps in Xinjiang are vocational training centres for people to learn Mandarin and other skills, not detention centres.

The treatment of Uighurs is an issue the Chinese government would prefer to keep out of the spotlight – long maintaining the camps in Xinjiang are vocational training centres for people to learn Mandarin and other skills, not detention centres.

A guard tower and barbed wire fences are seen around a facility in the Kunshan Industrial Park in Artux in western China's Xinjiang region. Source: AP

It has also always maintained its conduct in Xinjiang was about protecting human rights.

But at its Belt and Road forum earlier this week – a meeting of international leaders gathering to discuss President Xi Jinping’s signature economy policy - the treatment of Uighurs was one of the concerns raised by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “Human rights must be fully respected in the fight against terrorism and in the prevention of extremism,” a spokesperson for the Secretary-General Stéphane Dujarric said.

“Human rights must be fully respected in the fight against terrorism and in the prevention of extremism,” a spokesperson for the Secretary-General Stéphane Dujarric said.

Up to a million Uighurs are being held in extrajudicial detention in camps in Xinjiang, according to a group of experts cited by the UN. Source: AAP

“Each community must feel that its identity is respected.”

But that’s no consolation for those like 22-year-old Shakila Kutlan, who says she’s frustrated by not having any answers about the wellbeing of her relatives in China.

“I want to know if my grandparents are okay, and I want to know about my relatives,” she said. “There’s no reason for them to be in those camps, and we need to know if they’re alive or not.”

“There’s no reason for them to be in those camps, and we need to know if they’re alive or not.”

Shakila Kutlan says she’s frustrated by not having any answers about the wellbeing of her relatives. Source: SBS News

She said not having any answers had led her mother to fall ill from stress.

The rights group said its findings suggest the IJOP system tracks data of everyone in Xinjiang by monitoring location data from their phones, ID cards and vehicles, plus electricity and gas station usage.

"Psychologically, the more people are sure that their actions are monitored and that they, at anytime, can be judged for moving outside of a safe grey-space, the more likely they are to do everything to avoid coming close to crossing a moving red- line," Samantha Hoffman, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute's International Cyber Policy Centre, told AFP.

"There is no rule of law in China, the Party ultimately decides what is legal and illegal behaviour, and it doesn't have to be written down."

With AFP.