The Great Barrier Reef is suffering "mass bleaching" as corals lose their colour under the stress of warmer seas, authorities have confirmed.

The world's largest coral reef system, stretching for more than 2,300 kilometres along the northeast coast of Australia, is showing the harmful effects of the heat, said the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Aerial surveys detected coral bleaching at multiple reefs across a large area of the system, "confirming a mass bleaching event, the fourth since 2016," it said in a statement on Friday.

Flights over the World Heritage-listed site have confirmed there is bleaching in all parts of the marine park. Some of it is severe and coral mortality is evident from the air.

The Great Barrier Reef, home to some 1,500 species of fish and 4,000 types of mollusc, is suffering despite the cooling effect of the La Niña weather phenomenon, which is currently influencing Australia's climate.

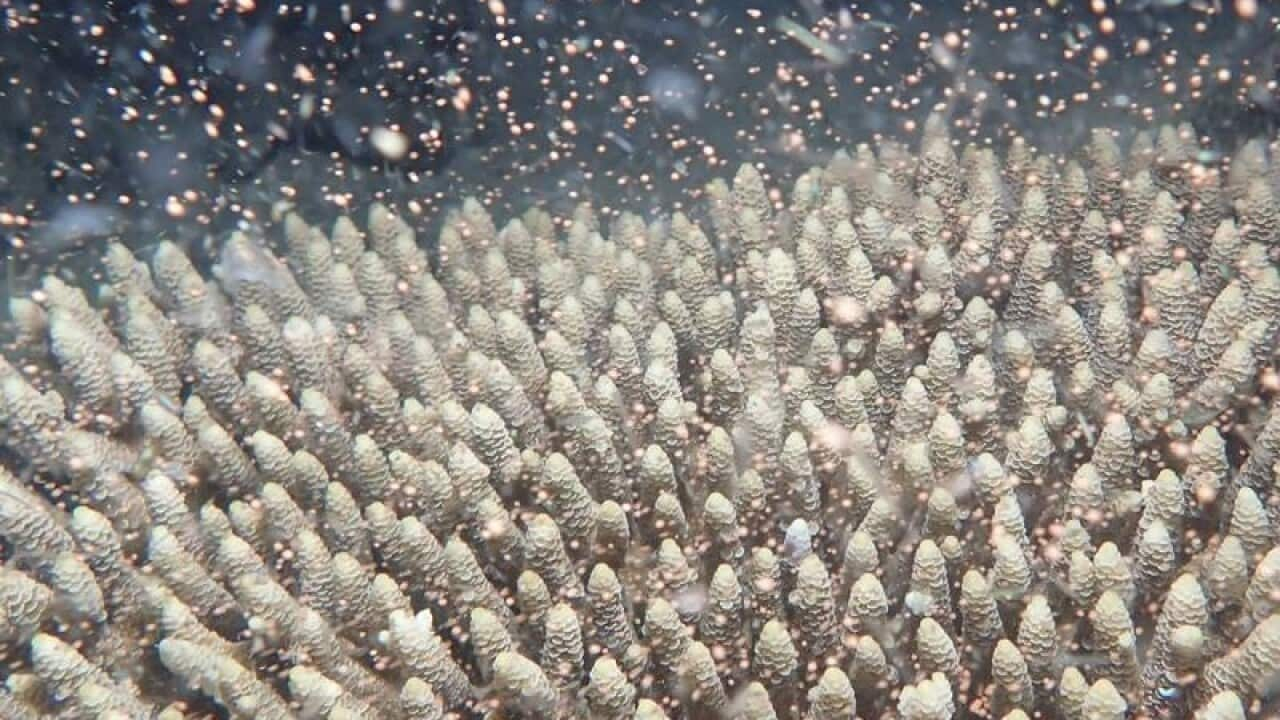

The area, which comprises about 2,500 individual reefs and more than 900 islands, suffers from bleaching when corals expel algae living in their tissues, draining them of their vibrant colours.

Though bleached corals are under stress, they can still recover if conditions become more moderate, the Reef Authority said.

"Weather patterns over the next couple of weeks continue to remain critical in determining the overall extent and severity of coral bleaching across the Marine Park," the Reef Authority said.

The mass bleaching update emerged four days after the United Nations began a monitoring mission to assess whether the World Heritage site is being protected from climate change.

Neal Cantin from the Australian Institute of Marine Science led the aerial surveillance work, in conjunction with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

"There are clear signs of bleaching through all four regions of the marine park and this is the fourth mass bleaching event to occur in the last seven summers. And it's the sixth to hit the Great Barrier Reef since 1998," he told AAP.

"The fact it's impacting such a large area of the marine park, during a La Niña year, is a clear sign of climate change-driven ocean warming. We expect these trends to continue and only accelerate in the future."

It's reasonable to expect that in the seven summers ahead, the reef could see another four bleaching events, Dr Cantin said.

Given it takes about 10 years for decent recovery of fast-growing corals, and longer for slow-growing species, the reef will not have enough time to recover between hits.

The UN mission is in Australia to speak with scientists, conservation groups, and government authorities. It will then report back to the World Heritage Committee, which may decide to list the reef as in danger.

'Ghostly white coral'

UNESCO's mission is to assess whether the Australian government is doing enough to address threats to the Great Barrier Reef - including climate change - before the World Heritage Committee considers listing it as "in danger" in June.

"The beloved, vibrant colours of the Great Barrier Reef are being replaced by ghostly white coral," said Greenpeace Australia climate impact activist Martin Zavan.

He pressed the government to show the damaged areas to the UN mission now inspecting the reef rather than the picturesque areas that have been untouched.

"If the government is genuine about letting the UN mission form a comprehensive picture of the state of the Reef, then it must take the mission to the northern and central Reef," Mr Zavan said.

"Here, corals are being cooked by temperatures up to four degrees above average, which is particularly alarming during a La Niña year when ocean temperatures are cooler."

The World Heritage Committee's decision to not list the Great Barrier Reef as being in danger last July surprised many, given UNESCO had recommended the listing weeks earlier.

When the UN previously threatened to downgrade the reef's World Heritage listing in 2015, Australia created a "Reef 2050" plan and poured billions of dollars into protection.

In their most recent splash to aid the reef, the government announced a further $1 billion in January to improve water quality, reef management and conservation, and research.

Amanda McKenzie, CEO of Climate Council Australia, said the world's oceans reached record high temperatures last year.

"Unfortunately, as more severe bleaching is reported across our beloved Great Barrier Reef, we can see these devastating events are becoming more common under the continuing high rate of greenhouse gas emissions," she said.

"To give our Reef a fighting chance, we must deal with the number one problem: climate change.

"No amount of funding will stop these bleaching events unless we drive down our emissions this decade."