9 min read

This article is more than 2 years old

Interactive

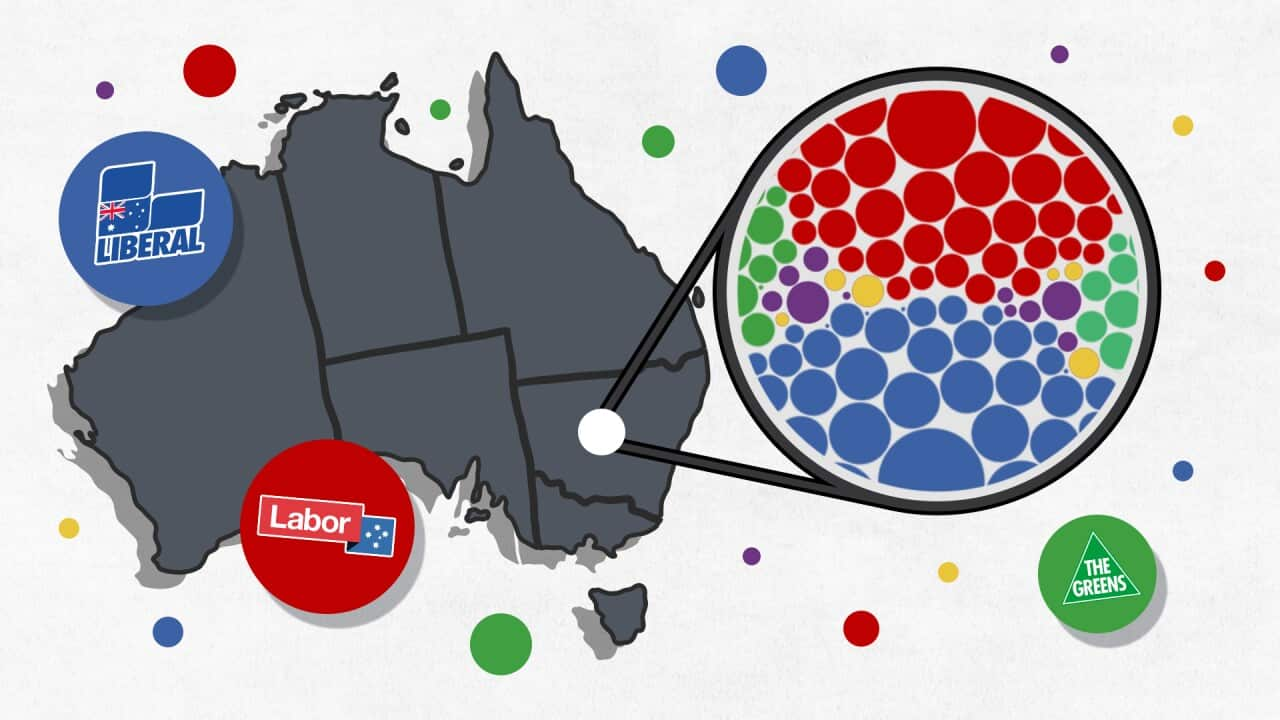

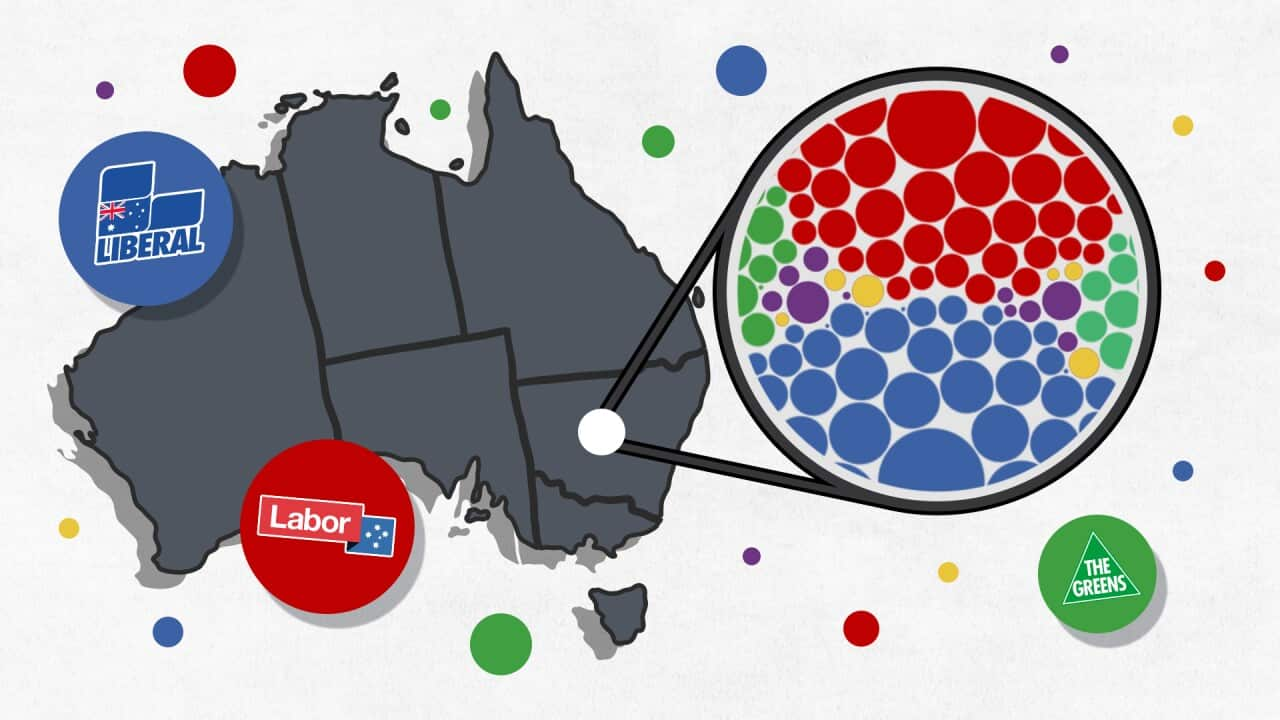

How politically diverse is your community?

You might know which party won in your electorate at the last federal election, but here's who else people around you vote for and why it matters.

Published

Updated

Source: SBS News

Do you live in a political bubble? With the 2022 federal election taking place on 21 May, eligible Australians are gearing up to pick their preferred candidates - but they won't all be the same.

While you might be sure of your own political leanings, what do you really know about those of the people living around you?

Using data from the Australian Electoral Commission on first preference votes from the last federal election in 2019, SBS News has created an interactive map showing the votes cast at polling locations within a two-kilometre radius of a chosen address.

You can search for where you live to reveal a breakdown of all the first preference votes by candidate, including independents, and overall results by party.

The interactive includes the ‘informal’ votes, or ballot papers that were incorrectly filled out, that were not counted towards the election result.

If your address brings up no polling stations, search for the nearest town.

Dr Jill Sheppard from ANU’s School of Politics and International Relations says exploring data at a neighbourhood level helps to dispel “unhelpful myths” about how Australians vote from one place to the next.

“There are grey areas between electorates that we don't know much about at all,” she says.

“Thinking about voters as members of a community or of a geographic region rather than an electorate is really helpful to understanding sometimes why campaigning is so hard, and sometimes why seats seem to go in a direction on election night that we might not expect.”

Dr Peter Chen, a senior lecturer in politics at the University of Sydney, agrees we “often don’t have a sense of the diversity in our local area”.

He says the rise of social media and the ways in which people are receiving information have prompted concerns about being insulated from a diversity of opinions and views.

“I think it is connected to the kind of slight moral panic about political correctness that we saw at the end of the 20th century, and then the new form of that around ‘cancel culture’ and ‘wokeness'.”

On the whole, most communities in Australia wouldn't be classed as being "political bubbles" with many different parties and candidates receiving nominations.

As well as exploring your own community on the interactive map, Dr Sheppard also points people to consider some other interesting areas.

The inner-west Sydney suburb of Newtown, for example, is mostly part of the Sydney electorate, held by Labor’s Tanya Plibersek since 1998.

The interactive shows there were 36,040 votes cast at 24 separate polling locations in a two-kilometre radius from central Newtown in 2019. Votes were cast for six parties and no independents, with Labor candidates receiving the most first preference votes at 51.76 per cent, followed by Greens candidates who received 25.84 per cent and Liberal candidates at 14.21 per cent.

Newtown, Sydney: A quarter of votes did not go to Labor or The Greens. Source: SBS News

“If we look at Queensland, specific neighbourhoods, let alone whole regions of Queensland, are full of political diversity. They're full of people who disagree fundamentally on the direction of the country.”

In central Mosman, a suburb in northeastern Sydney which is part of the Warringah electorate, there were 21,284 votes cast in a two-kilometre radius at nine separate polling stations. Votes were cast for nine parties and three independent candidates, with Liberal candidates receiving the most votes at 41.8 per cent, closely followed by independents who received 39.61 per cent.

Mosman, Sydney: Independents received 39 per cent of the votes. Source: SBS News

Bursting the political bubble

Political scientists say the notion of the “bubble” has emerged over the past decade to talk about group interactions and politics.

“This is the idea that we live around people who think and vote like us,” Dr Sheppard says.

She says neighbourhood effects on voting is a well-established idea in the United States, but less so in Australia, and can happen for two reasons: that people seek out a “safety net” of like-minded people in where they choose to live, and that being around people can “change our minds”.

“Social pressures are incredibly important when deciding how to vote - even between election cycles when we’re making up our mind on different single issues such as the same-sex marriage plebiscite ... This is a pretty well-established effect as well.”

Dr Sheppard says different kinds of “bubbles” range from the so-called Canberra bubble to those based on ideological and partisan divides.

“If you live in Canberra, people talk about politics all of the time and there is a real vibrancy around election time. Even though there may be differences between who we’re supporting and who we’re talking about, we do undoubtedly live in a very political bubble.”

Another bubble, she says, is one “where no one really cares about politics but we all vote the same”.

“I think, for better or worse, we need to give some credit to the people who live around us and the people we see day-to-day, and how they shape our political bias.”

Dr Chen says concerns about living in a political bubble should be moderated.

“Just because people might vote in similar patterns to people who are physically around them, doesn't necessarily mean they're unreflective about politics, but that they might, for very practical reasons, have similar concerns about their local infrastructure or the state of their local environment.”

“I think we can also recognise that when we are interacting with friends or family and we're talking about politics, that's not necessarily a problematic thing that we want people to engage in that sort of democratic discourse.”

Australia vs the world

Dr Sheppard says there is growing concern in the US that people are sorting themselves into neighbourhoods based on their political views.

“Now, we don’t have anything like that in Australia,” she says.

“What we do have is a greater number of people who have cast off their lifelong political identity. We have fewer cradle-to-grave Labor or Liberal voters than ever before, and so what we’ll see, just by default, is greater diversity in our neighbourhoods.”

Dr Chen says there are lessons to be learned for countries like Australia.

“That is about recognising political competition is a natural and appropriate sort of thing to occur in society. But it also says that political systems that facilitate a diversity of actors are also important.”

While Australia is widely described as having a 'two-party' political system - in which two major political parties dominate because they receive the majority of votes - Dr Chen says particularly through the Senate it “does enable a greater diversity of parties to be represented”.

He points to New Zealand as an example of a country that has a more expansive electoral system, allowing for a greater diversity of political parties.

Dr Chen says it’s important to point out that the interactive above refers to first preference votes in the House of Representatives, a system largely unique to Australia.

“It does tend to magnify the visibility of the two major party groupings, and that can lead to over-stating of their perceived level of currency with the community,” he says.

“As we have seen, the rise of people voting for minor parties and independents that has been occurring over quite a number of decades now, we have to recognise that Australians are quite interested in an electoral system that might give more voice to a broader range of political parties.”

Dr Chen says local community snapshots may be “extremely variable” across the country, but Dr Sheppard says when it comes to the numbers, marginal and safe seats “aren’t that different”.

“In any marginal seat, although the split of Liberal and Labor voters, or voters for any other major candidate is closer, even in a safe seat, you get about a third of the electorate who does prefer another candidate.”

“The difference between these safe seats is that they do get all the attention, they do get more resources, they do get more love from politicians.

“I think if we ran this kind of analysis over time in Australia, we would find that, if anything, fewer of us live in political bubbles than ever before.”

The Australian federal election will take place on 21 May.

Interactive by Ken Macleod. Graphics by Aaron Hobbs and Jono Delbridge. Words by Emma Brancatisano.