Children with this little-known autistic neurotype are often labelled as badly behaved, and their parents' approach to raising them is often questioned.

That's why the recognition of Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) in the Australian government's first as a profile of autism earlier this year has been welcomed by many parents and advocates for families of 'PDAers', as many refer to them.

Christina Keeble is both of those.

Dysregulation

Keeble worked as a teacher in specialist education settings for years before having her own children.

Despite her training and experience in supporting neurodivergent children, none of the conventional strategies seemed to work with hers; Keeble said they actually increased their dysregulation.

Both are autistic and have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

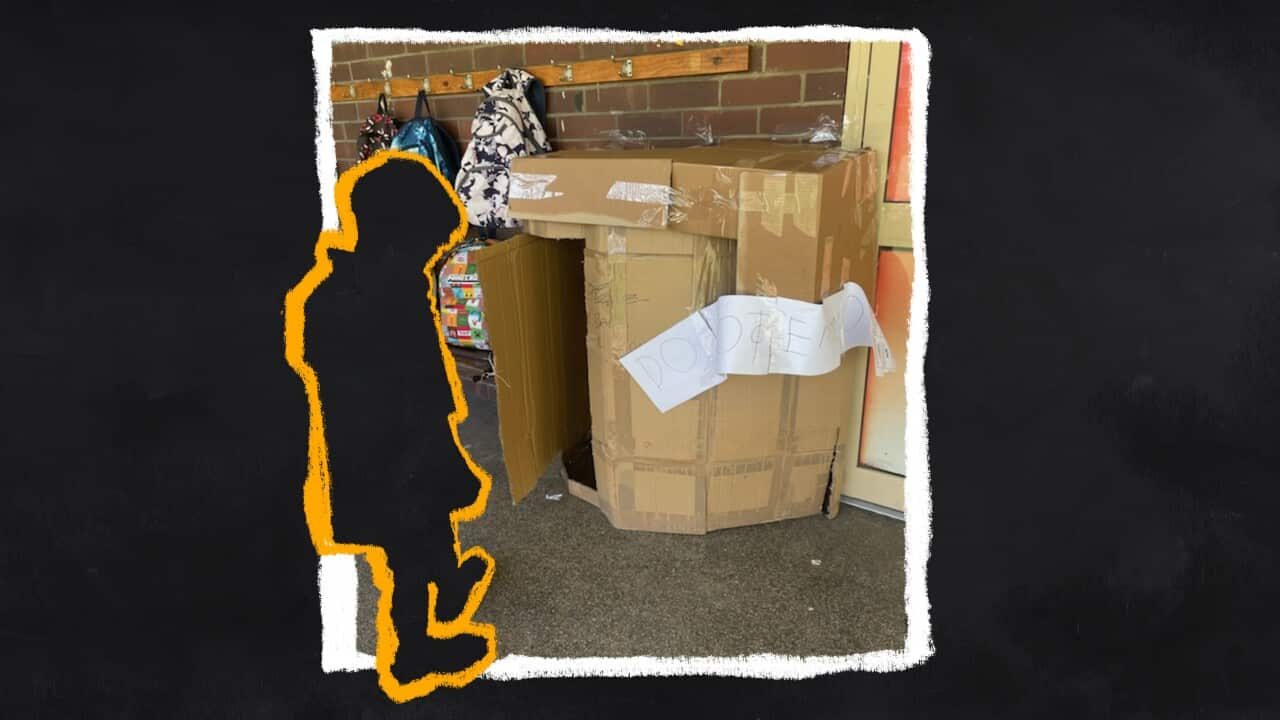

Christina Keeble had worked in specialist education settings for years, but the techniques she had been using to support neurodivergent children did not seem to work for her own kids. Source: Supplied / Jessica Roberts

"It could last for hours with anything we tried to alleviate their pain or distress not working."

She describes her children as neurodivergent PDAers.

Extreme demand avoidance

Children who fit the PDA profile may show what are often described as "challenging behaviours".

The term PDA was coined by British clinical psychologist Elizabeth Newson in the 1980s, and the PDA Society UK was established in 1997.

The society's website describes PDAers as people who share autistic characteristics but also have a need for control, "which is often anxiety related", and states for those with the PDA neurotype, "demand avoidance is a question of can't not won't".

Australia's national autism strategy recognises PDA as "a profile or subtype of autism".

The national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism in Australia, which was updated in 2023, described PDA as a set of characteristics that can co-occur with autism and is recognised as a behavioural profile within autism.

Recognition of PDA

PDA is not considered a standalone diagnosis like autism or , but it sits under autism as a certain presentation shown by some people on the spectrum.

While not a diagnostic test, the extreme demand avoidance questionnaire exists to measure behaviours associated with the neurotype.

In recent years, some Australian health professionals, such as paediatricians, psychologists and speech therapists, have started mentioning the profile in reports and diagnosis documentation of those who they consider fit the profile.

However, anecdotes about health professionals and educators telling parents PDA does not exist or is not recognised in Australia have been repeatedly shared in online support groups for those who fit the neurotype and their families.

This is likely why the simple mention of PDA in a blog on the National Disability Insurance Scheme website was shared to the 14,000 followers of the PDA Australia Facebook as "breaking news".

An Edith Cowan University (ECU) research study released this year on the experience of mothers of children with PDA noted: "Parents spoke about their experience of interacting with professionals in education and health-care settings who had limited understanding about PDA, invariably leading to misguided advice, poor support, or harmful practices."

Keeble said while it was "clear from the research that is available that it is currently a profile, not a stand-alone diagnosis, some professionals choose to not acknowledge it because it is not in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) or the ICD (International Classification of Diseases)."

Lowering demands

Those advocating for increased recognition of PDA believe that making a distinction between autism and those with the PDA profile of the condition is important because it requires a specific approach.

The PDA Society UK describes PDAers as "driven to avoid everyday demands and expectations [including things they want to do or enjoy] to an extreme extent".

While demands in the case of PDAers can be direct requests or questions from others, they can come in different forms. They can be things such as eating, sleeping, and showering, but PDA Society UK explains that indirect demands such as praise, expectations, or uncertainty have the potential to cause anxiety.

Keeble said PDA required a different approach to traditional parenting, and not providing PDA informed support could result in harm or trauma being caused to a child.

The PDA Society UK encourages a "proactive and collaborative approach" to parenting to manage anxiety in PDA children, with a focus on "picking their battles".

Its website advises: "In place of firm boundaries and the use of rewards, consequences and praise, an approach based on negotiation, collaboration and flexibility tends to work better in PDA households."

Some health practitioners have started to take an approach to those who fit the profile that reduces demands.

Keeble said once she was able to let go of the notion that things had to be a certain way in her household and with her children, such as everyone must sit at the kitchen table for meals, the stress that had been a constant in her household started to reduce.

"Now, when they have capacity, they naturally participate more with the demands of daily life. For us, it was finding the natural rhythm of our family," she said.

Keeble is now one of Australia's most well-known voices on PDA and works as a neurodiversity educational consultant.

A closer look at the DSM

PDA is not mentioned in the DSM, the reference guide for health professionals diagnosing autism or the International Classification of Diseases.

There have been a number of updated versions of the DSM, which have changed with new research and understanding; for example, homosexuality was listed as a diagnosable condition until 1973.

The current version was published in 2013 and is based on research done between 2000 and 2013.

David Trembath, professor in speech pathology at Griffith University, said he expected a new edition of the DSM would likely be released in the next few years, as they were generally published every 10 to 15 years.

However, he said he doesn't think PDA would be included in an updated version "given the lack of an extensive evidence base to support its existence as a separate and sufficiently distinct condition".

The PDA label

Trembath, who is also the co-chair of the group that developed the second edition of the national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism in Australia, said the guidelines recognise "PDA is a term used by some members of the community to help describe and explain some of the behaviours that are seen in autistic children and adults".

He said practitioners should be considering all available information to develop a holistic understanding of the person.

"It is not so much about whether the term PDA should be used, and instead all about understanding them as an individual," Trembath said.

"The guideline recommends an individualised approach, irrespective of how a person's behaviour is described, so we would say that a 'different approach' is required for each person, irrespective of whether their behaviour is described in terms of PDA or other terms."

The National Autism Strategy, which was launched in Perth in January by Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth, recognises Pathological Demand Avoidance as a profile of autism. Source: AAP / Aaron Bunch

"People who use the term say it helps to understand, talk about, and respond to the needs of the individual. Others will say it adds a layer of complexity, lacks an agreed definition and precision, and may be offensive to some people," he said.

Keeble described Trembath's position as "idealised" and not informed by the lived experience of PDAers and their families.

A push for more recognition

The recent ECU research produced what may be the first published research in Australia, giving insight into the experience of Australian families of autistic children with a PDA profile.

It highlighted the need for greater recognition, understanding and acceptance of the PDA profile and for flexible, informed and appropriate support for PDA children and their families.

Keeble, who is taking part in the Inaugural PDA Conference Australia in Perth later in the year, wants more professionals who work with young children to acknowledge PDA.

"Getting professionals to acknowledge the profile on reports and formal diagnoses letters gives parents the documentation which, they can use to advocate for their children our society requires," she said.