In a rare televised address, Putin suggested raising the state pension age by five years to 60 years for women, instead of the earlier proposed eight years to 63, among other measures.

However, he stuck to the overall government plan, warning of the collapse of the financial system and hyperinflation if the pension system was not reformed and evoking the country's enormous losses during World War II.

Putin, who is 65, proposed a number of concessions, suggesting early retirement for mothers with large families.

He also said companies that fire or refuse to hire employees because they are nearing pension age should face administrative or criminal liability.

The retirement age for men would still rise by five years to 65, as originally planned.

He insisted tough measures are needed, citing "serious demographic problems" stemming from the country's losses during World War II and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

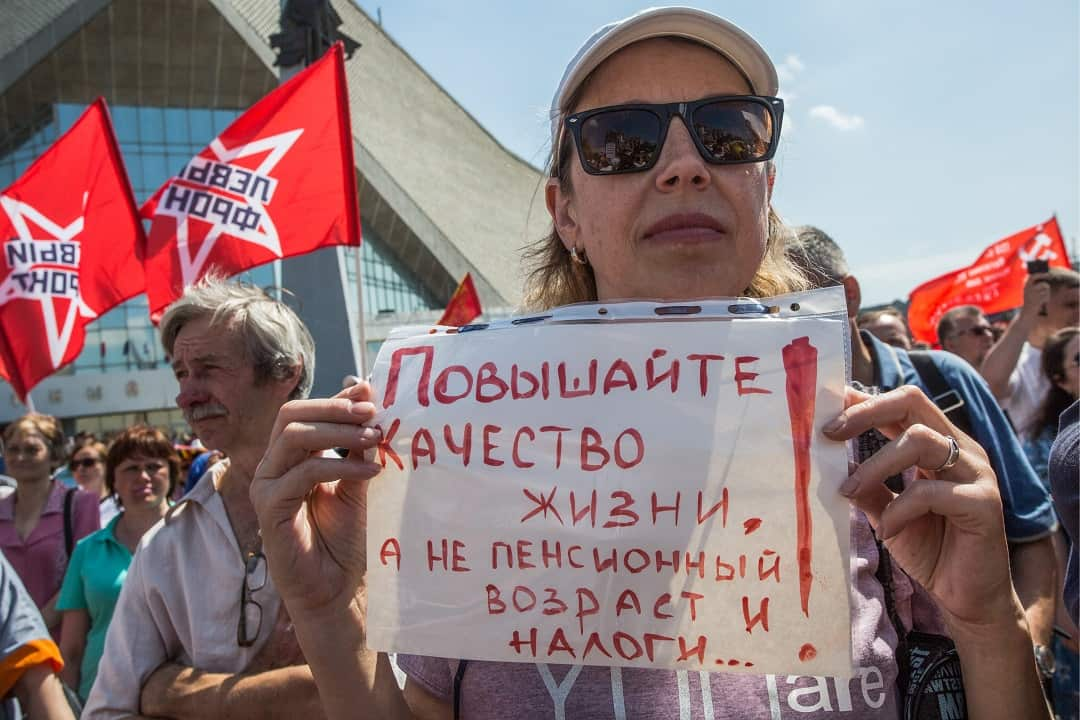

Russian pensioners protested in July against plans to raise the pension age. Source: TASS

"We will have to make a hard, difficult but necessary decision," Putin said.

"I ask you to treat this with understanding."

'Sweetening the pill'

The proposed reform - already approved by parliament's lower house in a first reading last month - has sparked a rare outburst of public anger, with tens of thousands rallying across Russia in recent weeks.

Putin had sought to distance himself from the unpopular measures and had been widely expected to soften the proposals to buttress his falling approval ratings.

He said that before announcing the amendments he had studied all "constructive proposals", including those put forward by the opposition.

But a Moscow court jailed his top critic, Alexei Navalny, for 30 days on Monday, just a couple weeks before he planned to stage a rally against the reform.

"Putin is panicking and is trying to sweeten the pill," Navalny wrote, calling on everyone to protest on September 9 despite his arrest.

The Communist Party said it would not back the reform despite the changes, adding it still wanted to conduct a referendum on the subject.

Most Russians have been against the hike in the retirement age and critics said the reform would essentially rob ordinary people of their earnings.

The proposal to raise the pension age prompted protests across Russia. Source: TASS

Navalny estimated that Russian women would lose around one million rubles ($14,700) if they retire at 60.

Unlike in some Western countries, pensions in Russia are meagre and many have to work past their state pension age to survive, while others rely on financial help from their children.

'Huge injustice'

Irina Petrova, a 44-year-old Saint Petersburger, said the reform was a "huge injustice", even despite the proposed changes.

"I am very much disappointed in the authorities in principle," she told AFP.

The pension age in Russia is among the lowest in the world and the proposed reform will be the first increase in nearly 90 years.

But given the low life expectancy of Russian men -- 65 years -- many would not live long enough under the reform to receive a state pension. The situation is different for women, who live on average to 76.

However, the government says the burden is simply too great for its stretched finances as the economy struggles under Western sanctions.

An elderly man holds a sign with a message reading "Gentemen in Power, Look at the Mess You Have Made" during protests against Putin's pension proposal. Source: TASS

Putin said that unlike a decade ago, the country's economy was ready for such reforms, pointing to the lowest unemployment rate since 1991 and increasing life expectancy.

Putin said the reform would allow authorities to better adjust pensions for inflation, raising them from some 14,000 rubles ($200 dollars, 175 euros) now to around 20,000 rubles ($353) a month in 2024.

He also said various categories of employees, such as miners, would get to keep their benefits and proposed doubling the size of unemployment allowances for people close to pension age.

Putin, who had previously vowed not to raise the pension age, has seen public trust in his presidency fall to 64 percent last month from 80 percent in May, according to VTsIOM state pollster.

The last time his approval ratings were this low was in January 2014, just months before his popularity skyrocketed following the annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

Political analyst Konstantin Kalachev said Putin essentially assumed full responsibility for the reform.

"His approval ratings will no longer keep going up," he said.