The collapse of global financial services firm Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 triggered the meltdown of the financial markets in the United States, but the contagion soon engulfed Eurozone economies including Greece.

What triggered the collapse?

At the centre of the crisis was skyrocketing levels of debt, facilitated through the banks’ use of financial products such as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) - whose value was based on another security.

Murdoch University politics and international-studies professor Kanishka Jayasuriya remembers the day Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. He said it highlighted the problems associated with a lack of regulation for such financial products. "These packages, full of securitised asset packages, then were sold on to other banks, other financial institutions,” he told SBS News, describing how the instability spread throughout the financial system in the US.

"These packages, full of securitised asset packages, then were sold on to other banks, other financial institutions,” he told SBS News, describing how the instability spread throughout the financial system in the US.

Traders at the New York Mercantile Exchange on September 16, 2008. Source: AAP

“And this is really the surprising and shocking thing about the global financial crisis [GFC], the web of debt that banks themselves were not aware of. And then the market responded by marking down these banks. The whole thing went into catastrophic crisis for the financial sector."

And the damage did not stop there.

Global impact

Greece became the symbol of countries hit far more deeply, where the debt crisis turned into a political and economic crisis.

The country's high debt level, large budget deficit, low competitive power and unstable political structure combined to leave a trail of destruction on society as a whole. Eventually, it became a eurozone crisis, and the repercussions continue to rattle across the continent a decade on.

Associate professor of international business and strategy Hussain Rammal, at the University of Technology Sydney, said the impact on Europe was devastating.

"It started from the US, but then it started exposing issues in Europe, because bad loans were coming to Europe,” he said.

“It started showing poor performance from governments, and we saw the case of the Greek government, which had borrowed a lot, spent a lot, but didn't have enough assets or any sureties to back that up. So it was just a poorly structured system of keeping tabs on things that just got exposed worldwide."

What happened in Australia?

In Australia, the effect was muted but extraordinary measures were enacted, including a $42 billion stimulus package designed to avoid recession and limit job losses. The Labor government, under Kevin Rudd, handed out bonuses will to middle- and low-income workers worth up to $950.

And it worked. While economic growth in Australia slowed significantly, the Reserve Bank of Australia said the country was largely protected from the more serious effects because Australian banks had little exposure to the US market and US banks. Resource exports to China, whose economy recovered quickly from the GFC, also protected Australia.

Resource exports to China, whose economy recovered quickly from the GFC, also protected Australia.

Then-prime minister Kevin Rudd speaking about the government's $42 billion stimulus package in 2009. Source: AAP

But Professor Jayasuriya said, while Australia was not seriously affected at the time, it has been swept up in a changing global economic and political climate that stems partly from the GFC.

"The issues of wage stagnation that we've seen in Europe and North America are problems in Australia as well,” he said.

“These kinds of economic difficulties and hardships are being reflected in Australia as well, albeit at a lower level, in the kind of fragmentation of political parties, in the rise of smaller parties like One Nation and in the rise of ... like in Europe and North America, the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment."

'Move towards nationalism'

Mr Rammal describes the result as a shift away from a global economy to a climate of so-called "economic nationalism" that can be attributed to the GFC.

He says it has resulted in the escalating trade war between the United States and China, for example, or the anger over countries forced to bail out others, as Germany did for Greece. Mr Rammal said the push-back is countries now trying to protect their own economies rather than strengthening the global economy.

Mr Rammal said the push-back is countries now trying to protect their own economies rather than strengthening the global economy.

A file photo of queue tags given to seniors who are lining up to withdraw a per-person maximum of 120 euros for the week in central Athens. Source: AP

“I think the big thing has been that move towards nationalism. So we're seeing more borders being closed, more about 'countries first' before thinking about global trade.

“And I would say part of that is due to the global financial crisis. And we're seeing the effects of that with Brexit, with nationalism in the USA and more and more European countries trying to close their borders for international trade."

Could it happen again?

Following the crisis, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority put stronger banking regulations in place, aimed at protecting Australia's financial sector from global downturns. Despite that, Mr Rammal said, industry analysts are warning the world may be heading for a similar crisis in the future.

Despite that, Mr Rammal said, industry analysts are warning the world may be heading for a similar crisis in the future.

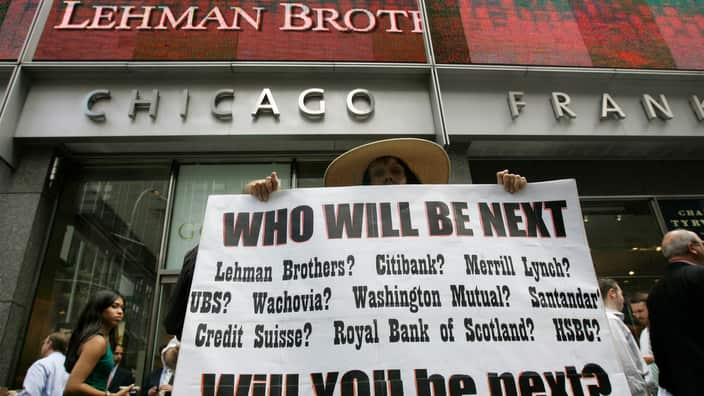

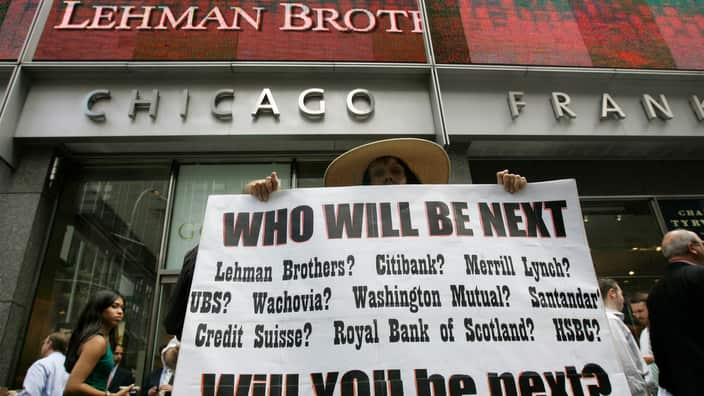

A sign in front of Lehman Brothers in New York on 15 September 2008 Source: AAP

It is not a lack of strict laws to regulate lenders, but more an issue with the implementation of the laws, according to Professor Rammal.

“So, as more and more new economies grow, there will be a risk that people will try and take shortcuts, and we may end up with a similar situation in the future."

READ MORE

Most Australians 'fear second GFC'