When it comes to assessing the severity of the Delta variant of COVID-19 in children and deciding whether and when to vaccinate them, Australia is several months behind many other countries.

But this can be helpful, experts say. It gives us the opportunity to monitor vaccinate rollouts elsewhere and their effects on young people.

Millions across the northern hemisphere are preparing for the new school year in the coming weeks, with some children vaccinated and some not. And as Delta outbreaks continue to spread across Australia and homeschooling drags on, this mass migration back to classrooms is being seen as a global experiment.

It will not only give us more information on vaccine efficacy but will also help us to answer: can our unvaccinated children return to school safely? If adults around them are vaccinated, does this offer them enough protection? And if not, when will Australia look to further ramp up its vaccination program for children?

What is Australia’s current advice on vaccinating children?

On Friday, Australia announced .

The federal government approved the expansion on the recommendation of the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) to broaden the rollout to the cohort following a review on the safety and effectiveness of vaccines overseas, as well as modelling on the benefits of vaccinating this age group. The ATAGI the government offer it to those aged between 12 and 15 with specified medical conditions that increase their risk of severe COVID-19, as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and those living in remote communities.

The ATAGI the government offer it to those aged between 12 and 15 with specified medical conditions that increase their risk of severe COVID-19, as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and those living in remote communities.

A boy receives his first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine in Oeiras, Portugal. Source: Xinhua News Agency

Which vaccines are approved for children?

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved the Pfizer vaccine as safe and effective for those aged 12 to 15 in Australia on 23 July.

from 30 August, and for those aged between 12 and 15 from 13 September.

The Moderna vaccine is expected to arrive in Australia from October, but at this stage, it has also only been approved for those aged over 18. Like Pfizer though, Moderna is expected to be approved for those aged 12 and over in due course.

AstraZeneca is only available for those aged 18 and over.

When it comes to vaccinating children under 12, there is at present no recommendation in Australia. Health Minister Greg Hunt says decisions will hinge around the results of clinical trials of Pfizer and Moderna on children currently underway overseas, principally in the US, with data expected towards the end of the year.

What does the modelling say about vaccinating children?

The , released in August to advise Australia's national COVID-19 response, refers to everyone over the age of 16 as eligible for vaccination, with targets set at achieving 70 per cent to bring about reduced restrictions and at 80 per cent for the significant easing of them and the likely end to lockdowns.

The government didn’t ask the Doherty Institute to factor in those under 16, so the model treats this age group as unvaccinated. It concludes that expanding the vaccine program to 12 to 15-year-olds “has minimal impact on transmission and clinical outcomes for any achieved level of vaccine uptake”.

Instead, it works on the basis that vaccinating adults protects children by reducing the number of COVID-19 cases in the community and therefore transmission. Professor Jodie McVernon is the director of epidemiology at the Doherty Institute. She says while it's concerning when children become infectious, it's really because they come into contact with the most people.

Professor Jodie McVernon is the director of epidemiology at the Doherty Institute. She says while it's concerning when children become infectious, it's really because they come into contact with the most people.

Melbourne students returning to school in July. Source: AAP

She says part of the reason children appear to be making up a larger percentage of positive cases in some parts of the world is due to successful adult vaccination programs.

"Clearly in countries where there have been high levels of immunisation uptake, and where schools have been one of the more free social venues, we have seen many reports of increasing representation of children in the disease cases, and we would expect that within that context,” she said.

The protection offered to children through high levels of adult inoculation has been proven in parts of the US. Areas with high vaccination levels have seen lower levels of community transmission, including the lowest rates of paediatric infection.

But some health experts believe leaving children unvaccinated may encourage COVID-19 to spread among this cohort and potentially mutate into new variants.

Epidemiologist and public health medicine specialist Professor Tony Blakely from the University of Melbourne is one of them. He believes that omitting children means the Doherty Institute modelling is flawed.

“If we open up the borders at 80 per cent vaccination coverage of only adults, our modelling suggests you’d still be in lockdown 30 per cent of the time, which is not good. But if you included children aged five to 16 in the 80 per cent as well, that would halve the amount of time in lockdown,” he told ABC Radio.

“That makes sense because they hang out together in schools, and if you have that reservoir unvaccinated, you’re never going to get on top of it.”

released on 24 August backs up his claims. It suggests the government’s current national plan puts too many lives at risk and children will directly benefit from vaccination.

The researchers - Professor Quentin Grafton from The Australian National University, Dr Zoe Hyde from the University of Western Australia and Professor Tom Kompas from the University of Melbourne - say at least 90 per cent of all Australians, including children, should be vaccinated against COVID-19 before the country can open up safely.

Are children more at risk of Delta?

The current wave of Delta spreading in some Australian communities is seeing more children infected, with them accounting for significant proportions of infections in NSW and Victoria, while schools have been a principal cause of clusters in Queensland and the ACT.

It’s a trend that’s replicated around the world. The US has seen sharp increases in children hospitalised during July and August. But case numbers among children there are rising only slightly higher than among the general population, which could be because they form an increasing share of the unvaccinated.

But children won’t necessarily be the ones who get severe infections, with older age groups still more likely to be hospitalised or die,.

Australian paediatric health experts agree Delta in unvaccinated children and adolescents is no major cause for alarm.

“There’s a small proportion of children who become unwell and require hospitalisation but that number remains very low,” paediatric infectious diseases expert Professor Andrew Steer at the University of Melbourne said.

Higher levels of hospitalisation in children with COVID-19 have been linked to conditions including cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, obesity and diabetes.

Professor Robert Booy, an infectious diseases paediatrician at the University of Sydney, says parents should be reassured that the outbreaks occurring in healthy preschool, primary school and secondary school students are resulting “mostly in children having a cold”.

And while children and adolescents seem less susceptible to long COVID, more research is needed.

Nevertheless, Australia’s unvaccinated children will remain vulnerable as restrictions ease.

Professor Booy says the next two months will be about gathering evidence on vaccine safety and efficacy from northern hemisphere nations as children and adolescents return to school.

“The trials and real-world experience of millions of children will inform us about what we do,” he said.

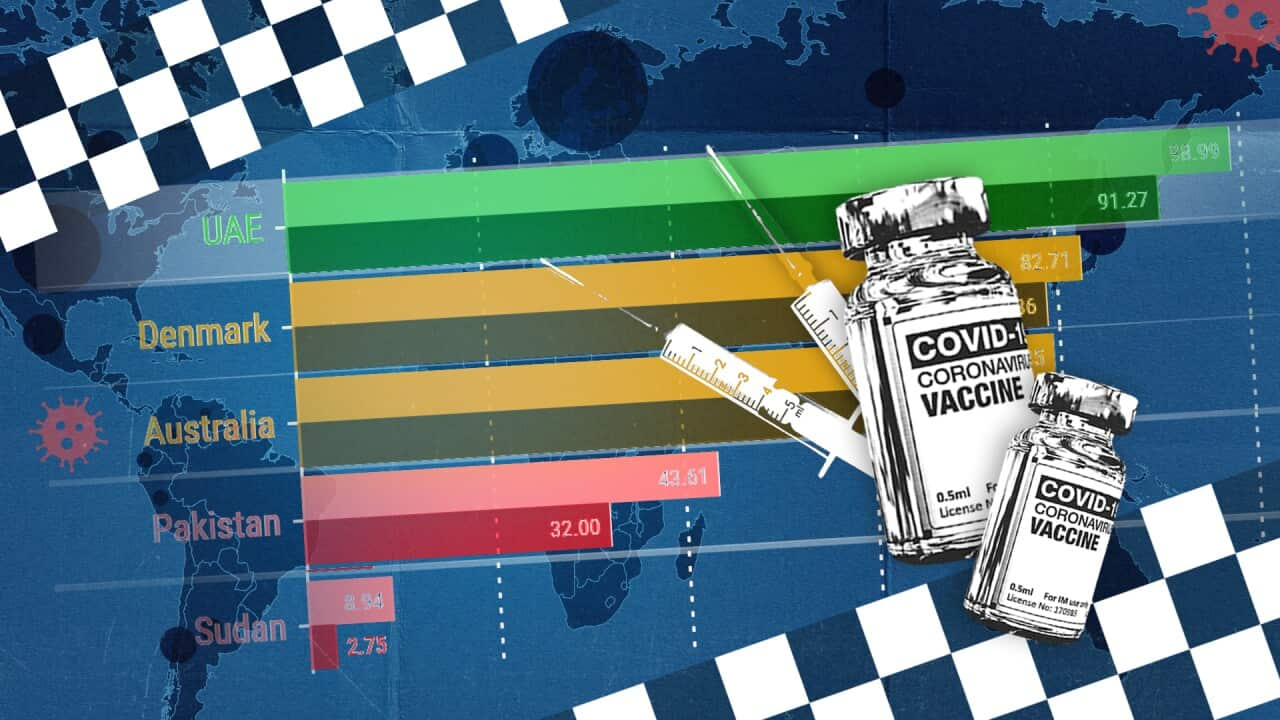

Which countries are vaccinating children?

Countries around the world have been vaccinating those aged 12 to 15 for some time, with many in the northern hemisphere ramping up the rollout in recent weeks ahead of the beginning of the school year.

In May, Canada became the first country to authorise COVID-19 vaccines for children aged 12 to 15. As of 7 August, nearly 75 per cent of the country’s 12 to 17-year-olds had received at least one dose of vaccine, with more than 50 per cent fully vaccinated.

In the US, everyone aged 12 and over is eligible for vaccination, while clinical trials are underway for children as young as six months old. Heralded as a leader in vaccine rollouts, Israel started vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds from early June. From late July, its government announced it would also approve vaccines to those aged five to 11 with underlying medical conditions.

Heralded as a leader in vaccine rollouts, Israel started vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds from early June. From late July, its government announced it would also approve vaccines to those aged five to 11 with underlying medical conditions.

A teenager is vaccinated in Pamplona, Spain. Source: Europa Press

For children aged three to 12 who remain ineligible for vaccination at present, . Those found to have antibody protection against COVID-19 after having an unrecorded or latent case will not be forced to quarantine when exposed to a coronavirus patient, a move aimed at limiting schoolyear disruptions.

On 21 August, India , which is the first approved for children older than 12 in the country.

In Europe, France boasts one of the most impressive rollouts among 12 to 17-year-olds. They have been receiving vaccinations since mid-June. Recent data shows more than half of its five million 12 to 17-year-olds have had at least one dose, with more than 25 per cent now fully vaccinated.

From the end of September, those over 12 in France will need to show their health passport to enter venues including cafés and cinemas. They won’t need it to access school but - as an apparent incentive for parents - only unvaccinated children will be sent home if a classmate tests positive to COVID-19.

The UK has adopted a more cautious approach, deciding only to vaccinate 12 to 15-year-olds considered vulnerable at this stage, with plans to also vaccinate those living with at-risk family members.

How can we protect children while they are unvaccinated?

Mr Morrison has said, for now, the best way for parents to protect their children from COVID-19 is to get vaccinated themselves.

But vaccinating teachers, many agree, is a priority, though at present it’s not compulsory.

Professor Booy believes it should be mandatory for teachers and carers who work with children with health conditions or disabilities to be vaccinated, and it should be highly recommended for others.

“A teacher in his or her 30s is four times more likely to die of COVID than a teenager. A teacher in their 50s is 40 times more likely to die of COVID than a teenager. So let’s get teachers vaccinated; that’s a priority,” he said.

But it’s not just about teachers. Professor Steer says vaccination levels must be high across the entire school community to keep children and adolescents safe.

“Vaccinating those who are eligible around children is a really important way of protecting them. This means teachers, childcare workers, school staff, household contacts and family members who are eligible.”

Ventilation is also key. The provision of clean air through air purifiers and filtration systems not only protects against COVID-19 but also other airborne pathogens and has been the focus of governments in some Asian and European countries since the start of the pandemic.

A found decent ventilation was more effective in reducing COVID-19 in schools than mask-wearing.

Other measures include masks, hand hygiene, staggered break times and rotating school days to ensure distancing, organising kids into bubbles, moving teachers between classrooms rather than children, minimising adults on school grounds, and testing children and staff regularly.

The case for returning to school

Transmission risks also need to be balanced against children’s overall wellbeing, health experts say.

Dr Asha Bowen is head of the Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases at Perth Children's Hospital and head of vaccines and infectious Diseases at the Telethon Kids Institute. She says every day at school matters, and closing them is a risk on its own.

"We know that online learning is nowhere near as efficient for the youngest children, and for those children who are living in situations of disadvantage, school is a safety measure as well,” she said.

“It's trying to balance that sort of need for face-to-face learning and the need for schools to be open with the attempts to control the transmission of the virus, and to minimise population movements."

Professor Steer, who worked on new paper - which describes keeping schools open as a “national COVID-19 policy priority” - says recurrent lockdowns and school closures have huge effects on the health and educational outcomes for children, which have the potential to be more damaging than actually contracting COVID-19.

“Allowing children to return to school, to enjoy play and sport, spend time with their friends and family, is obviously really important for their social development, mental health and wellbeing,” he says.

“These indirect effects of the pandemic should also be considered in vaccination policy.”