Key Points

- Two incidents involving elderly women in aged care homes have raised questions about the use of force.

- Both women have dementia, and one is now receiving end-of-life care after being tasered.

- Are there rules or restrictions for police and staff in care homes for these situations?

Two separate incidents involving elderly women with dementia have raised questions about the actions of police and the use of force.

Both incidents took place in aged care homes and resulted in frail women being hospitalised, with one now receiving end-of-life care.

So why is force being used against patients in aged care facilities, are there rules around it, and is it ever warranted?

What happened at the aged care facilites?

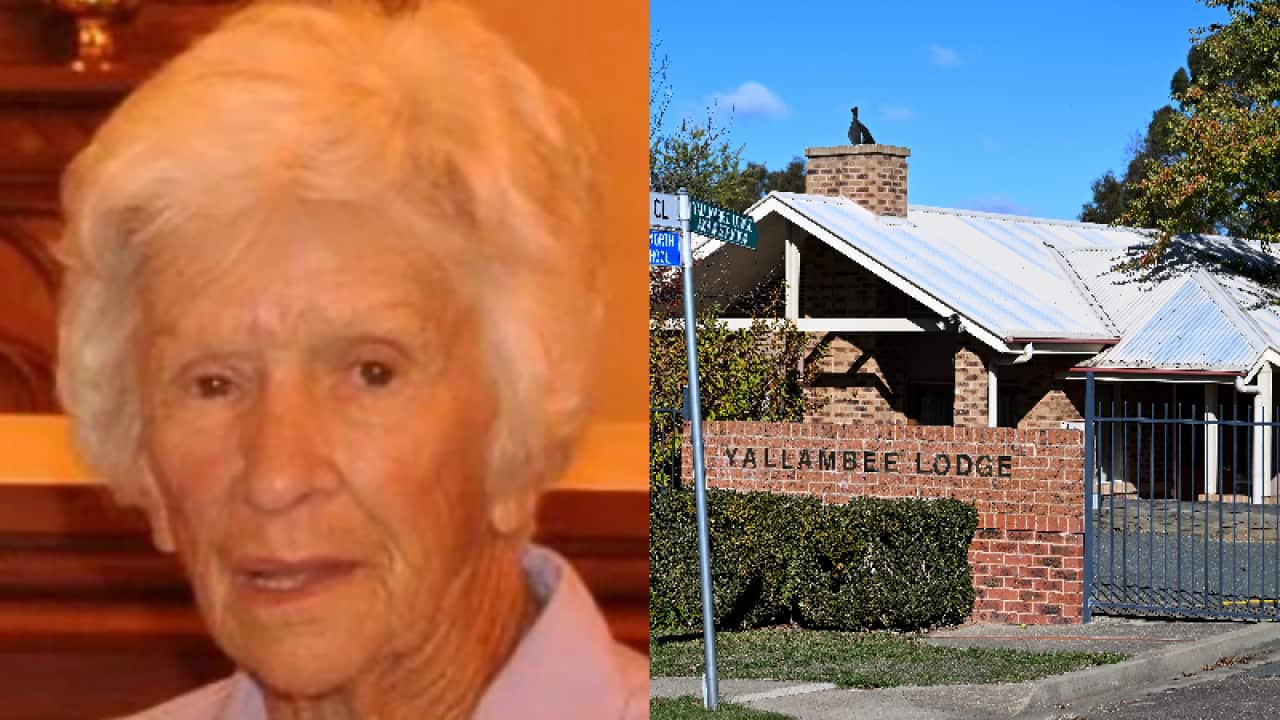

Last week, Clare Nowland - a 95-year-old grandmother who uses a walking frame - was tasered by police.

Staff at the Yallambee Lodge aged care facility in Cooma, NSW, called paramedics and police when she was found holding a steak knife.

During negotiations, Ms Nowland moved at a slow pace towards the doorway where the officers were standing and was hit once with a taser, falling to the floor and hitting her head.

She is now receiving end-of-life care, surrounded by her distraught family.

The case is being investigated by the homicide squad and the Professional Standards Committee of NSW Police and overseen by the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission.

In 2020, Rachel Grahame was forcibly handcuffed by police after taking a lanyard and electronic device from a desk in St Basil's aged care home in Sydney.

In footage, she can be heard crying for help and questioning officers during the incident.

Her family sued NSW police in the state's district court, accusing them of assault, battery and false imprisonment, and received compensation.

Ms Grahame's daughter Emma told The Guardian she does not believe police should have been called.

“The point is really, that they shouldn’t be there in the first place,” she said.

A NSW Police Force spokesperson told SBS News it would be inappropriate to provide comment as the issue was a civil matter that had been settled.

A 95-year-old woman is receiving end-of-life care after being tasered by police at Yallambee Lodge. Source: AAP / Lukas Coch

What are the guidelines for using force?

The NSW Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 says a police officer "may use such force as is reasonably necessary" to make an arrest or prevent an escape.

According to NSW Police guidelines, an officer can use a stun gun when violent resistance is occurring or is imminent or when an officer is in danger of being overpowered.

Both of these incidents happened in aged care homes, involving elderly women with dementia.

Ms Nowland is 95 and weighs 43 kilograms, while Ms Grahame was 81 and weighed 45 kilograms when she was handcuffed.

NSW police commissioner Karen Webb said police understood the gravity of the situation. Source: AAP / Dan Himbrechts

Facilities are required to respond effectively to incidents of abuse, to report any relevant incidents, and to raise awareness in the organisation to lower the risk of elder abuse.

The government's Serious Incident Response Scheme (SIRS) is designed to be used after incidents and near misses (situations that did not result in harm, but could have) and aims to support those affected and reduce the risk of recurrence.

According to SIRS, unreasonable use of force is physical contact that ranges from the use of unwarranted physical force to a deliberate and violent physical attack.

It includes behaviour such as shoving, pushing, hitting, punching, kicking or rough handling.

The government also funds Dementia Training Australia to deliver the Dementia Training Program, and the revised Certificate III in Individual Support (Ageing) will include mandatory components on supporting people with dementia.

The Older Persons Advocacy Network (OPAN) has said the incident at Yallambee Lodge highlighted "huge skills gaps" in aged care staff training to support people with dementia.

"We know that people with dementia require a certain level of care to ensure they are looked after safely and compassionately," OPAN CEO Craig Gear said.

“Unfortunately, we also know there is a huge skills gap across the country between aged care workers who are trained to care for dementia patients, and those who are not.”

SBS News has contacted the United Workers Union and the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation for comment.