Policing Western Australia’s outback town of Warakurna is not your average affair. There are only two officers who run and oversee day-to-day operations, and both are Aboriginal.

Reports of racial profiling and more than 432 Indigenous deaths in custody since 1991 have contributed to mistrust in law enforcement among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

But in Warakurna, 1,716kms North-East of Perth, with a population of about 230, there is a harmonious relationship between police and the Yarnangu community as local officers use Aboriginal culture to gain trust and respect from residents.

Senior Sergeant Revis Ryder and Senior Constable Wendy Kelly are Noongar officers from Perth. They have patrolled the town for the past few years and use Yarnangu Lore and Australian law to help maintain a positive relationship. "If there was conflict, we would invite the community to get together with us and try and resolve things so that it didn’t erupt into something else,” Constable Kelly told SBS News.

"If there was conflict, we would invite the community to get together with us and try and resolve things so that it didn’t erupt into something else,” Constable Kelly told SBS News.

Senior Sergeant Revis Ryder, Yarnangu Elder Daisy Ward and Senior Constable Wendy Kelly. Source: Pink Pepper/Persicope Pictures

“With the youth in the community, we would go through Elders in the community and other community members to help resolve those sorts of issues as well.

“If people do something wrong, obviously if we needed to, we would investigate incidents and possibly charge someone, so there is that too.”

Aboriginal lore has been passed down from generation to generation through dance, stories and song. Elders are the keepers of the lore and their opinion around the lore can carry great weight within their respective communities.

The lore governs each community, with some parts remaining private and only able to be discussed by certain people within that community, such as men's business and women's business.

When someone breaks the lore or law, it is dealt with by the Elders in a meeting, and punishments can vary depending on age, sex, status, previous offences and the offence breached.

The Warakurna Police Station is the only known Indigenous-run police station in Australia and Constable Kelly believes there should be more like it.

“If we have non-Indigenous people working with us, we can teach them we aren’t trying to take over things, it’s just sometimes there needs to be someone to suggest a different approach,” she said.

“With the knowledge I have now, I feel I need to pass that on to others.”

Connecting through local culture

Learning the most prominent local language of Ngaanyatjarra was an important thing for Sergeant Ryder to do when he first moved to the community three years ago. He said speaking the same language is a key step towards reducing confrontation.

“When I first arrived in Warakurna, I identified the language as a barrier I needed to overcome., I haven’t learned it fully but a lot of the words I do understand and that has gone a long way with the community and surrounding communities,” he said.

Sergeant Ryder said community engagement and outreach is crucial in maintaining a level of trust between officers and residents.

Through also coaching the local football team, he said it “helps to break down that barrier and build a rapport with the community”. Crime in Warakurna is minimal and Sergeant Ryder said youth crime had fallen since he and Constable Kelly started patrolling the area.

Crime in Warakurna is minimal and Sergeant Ryder said youth crime had fallen since he and Constable Kelly started patrolling the area.

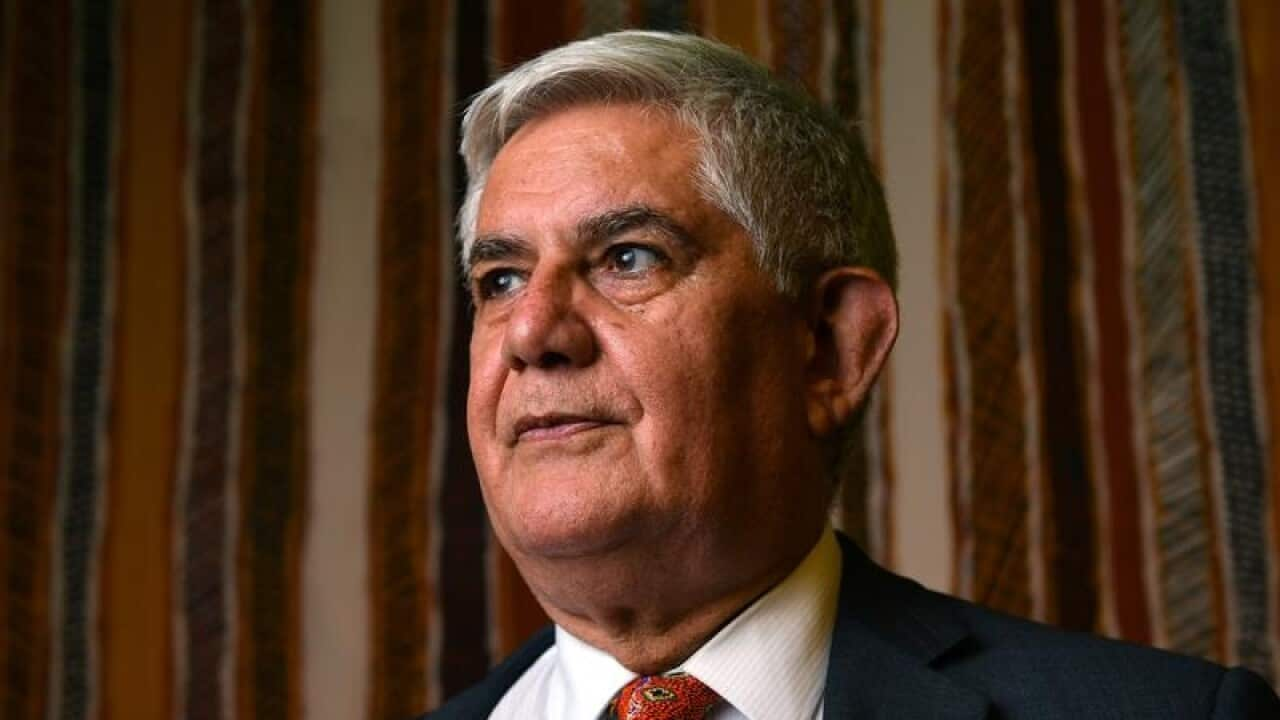

Senior Sergeant Revis Ryder believes community engagement and outreach is crucial in maintaining a level of trust between officers and residents. Source: Pink Pepper/Persicope Pictures

“We don’t really have a high crime rate so a lot of the stuff we deal with is to do with domestic violence ... the growling and the arguing between families and partners,” he said. “But even that is not a major problem.”

Such incarceration rates are not replicated across the country.

Last week the prison statistics for the March quarter were released, showing the average daily number of . Almost three-quarters of that increase was in .

The highest imprisonment rate was in Western Australia with 4,118 Indigenous people per 100,000 being taken into custody.

Indigenous adults now make more than , while only making up 3.3 per cent of Australia’s population.

When asked about racism in the police force in the wake of recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Australia, Sergeant Ryder said “racism comes in all forms”, but didn’t disclose exactly where it was present.

“In my time I have witnessed it, but I’ve dealt with it quickly at the time,” he said. “I deal with it and move on."

Constable Kelly echoed his sentiments and said the issue belongs more with non-Indigenous officers and them “not having an understanding of the way that communities interact”.

“It’s just an opportunity for officers to do more cultural awareness training and do some research before they go out to communities,” she said.

“From the non-Indigenous side, there needs to be an understanding of what they should be doing when they go to communities, like who do you speak to, find that out because it will help.”

Protests shine light on custody rates

Last weekend, in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States and with Australia’s First Nations people, calling out police brutality.

Sergeant Ryder said he hopes the movements will bring about change.

“We can’t keep going the way we are,” he said. More than 432 First Nations people have died in custody since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1991. The report found that although each death differed, there was abuse, neglect or racism at the heart of them all.

More than 432 First Nations people have died in custody since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1991. The report found that although each death differed, there was abuse, neglect or racism at the heart of them all.

Black Lives Matters demonstrators gather in Sydney in June. Source: AAP

In order to help prevent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody, 339 recommendations came from the royal commission, but 19 years on First Nations people continue to die in custody.

One of the main recommendations was that prison be the last resort, and Constable Kelly said utilising lore could be a step in the right direction.

“The people have got used to the style of policing that we have ... we were out and about all the time doing things with the community, doing things for the community, so it does work,” she said.

The unique policing in Warakurna is now the subject of short-form documentary Our Law, written and directed by Cornel Ozies and produced by Taryne Laffar and Sam Bodhi Field.

“Senior Sergeant Revis Ryder and Senior Constable Wendy Kelly are revealing a new way of working and we’re hoping it will really influence the rest of the country,” Bardi and Jabbir Jabbir woman Ms Laffar said.

“The need is really to address the issues between police and Indigenous Australians.”

Our Law is screening online as part of the Sydney Film Festival until 21 June and will be shown on on Monday 22 June at 8.30pm.