Exclusive: Proposed new legislation will today be unveiled to ban dolphin captivity in New South Wales, following the death of a baby dolphin at a marine park in 2015. The move is part of a wider push to end the practice across Australia.

By Robert Burton-Bradley and Sylvia Varnham O’Regan

5 May, 2016

It was May 2015 when staff at Dolphin Marine Magic, a theme park on the New South Wales coast, noticed something was wrong with their youngest dolphin, a baby known as “Ji”.

The inside of the animal’s mouth was pale and a blood test revealed he was suffering from anaemia. After some treatment, Ji seemed to return to full health. But in August that year, he fell ill again after swallowing leaves, sticks and a small piece of metal, causing an ulcer to form in his belly. Surgery wasn’t an option – dolphin skin has poor elasticity and is difficult to sew shut – so a vet decided the only option was to manually extract the leaves. On the day of the procedure, Ji and his mother “Calamity” were taken to a small medical pool, aside from the two main pools at the park’s centre. Ji was still a dependant calf, and staff knew that separating him from his mother during the procedure would cause them both distress.

Staff at the park say Ji was a happy and inquisitive animal.

A table with a foam mattress was set up at the pool and Ji was given a small dose of Valium and placed on top. Because of the sloppy nature of the leaves mixed with blood in his stomach – described as “black and tarry” – it was decided that the only way to remove them was to reach a hand into the baby animal’s stomach and pull them out. A staff member who was familiar with the process was tasked with the job, but something went wrong during the procedure and Ji suffered a heart attack and died. Attempts to put him back in the water to revive him were unsuccessful.

When news of the death broke, the park went into information lockdown, refusing to say what had happened. This fuelled angry speculation about how a dolphin so young could abruptly die. SBS is revealing this information publicly for the first time.

The park’s manager, Paige Sinclair, still refuses to publicly release the autopsy report into Ji’s death and accuses animal rights groups and media organisations of spreading misinformation about her business. Moreover she says a campaign to close the park, spearheaded by advocacy group “Australia for Dolphins”, has led to safety threats against her staff. But the group – which SBS can exclusively reveal will today announce new legislation to ban dolphin captivity in New South Wales, presented by NSW Labor and co-sponsored by the NSW Greens and the Animal Justice Party – is undeterred by the increasingly personal nature of the debate. Spokeswoman Jordan Sosnowski says Dolphin Marine Magic is just the first battle in a wider war to ban the keeping of dolphins in captivity, Australia-wide.

“There is a global trend all around the world of people turning against marine parks because they are starting to realise that animals performing tricks for entertainment isn't good for them,” she says.

“People no longer want to see dolphins in captivity.”

Jordan Sosnowski says Australia for Dolphins has the support of many other animal welfare and animal rescue groups.

Unlike the sleek, corporate feel of Australia’s only other remaining dolphinarium – Sea World on the Gold Coast – Dolphin Marine Magic in Coffs Harbour recalls a different age of keeping and training captive animals. The park is home to five dolphins, which guests can touch and even get “kisses” from, as well as a small number of seals and penguins. Outside the front entrance, Australian flags wave in the breeze near a large sign displaying the company’s phone number, 1300-KISSES.

But the park’s sunny exterior belies a bitter stand-off brewing behind the scenes. Australia for Dolphins wants the dolphins moved out of the park and into a “sea-pen” enclosure, where they can live out the remainder of their lives. The group has spread its message on billboards, buses and through social media, arguing the park is keeping Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in enclosures that allow them to swim less than 1 per cent of their usual range in the wild. Ms Sosnowski says there is a wealth of scientific evidence that proves the physical and psychological problems dolphins face in captivity and that any claim from the park to the contrary should be regarded with cynicism.

Signs around Dolphin Marine Magic offer dolphin kisses to guests.

“I think the main evidence for that is the fact the baby dolphin died last year at Dolphin Marine Magic,” she says. “This dolphin had swallowed so much leaf litter, which you can imagine that would have been a very slow and excruciating death.”

Beyond questions over Ji’s death, Australia for Dolphins has accused the park of breaking NSW captive animal standards by keeping too many animals in pools that are too small, and by allowing people to ride dolphins and kiss dolphins and seals. The park says kisses with animals are not in breach of any regulation. It insists there are no rides, just “swims” with the animals, and that its pools are all compliant. The park charges $420 for one of these swims or $1460 for a family of up to four people.

“I’m a great animal lover and it’s important that in my duty of care, my custodianship, that I make sure these animals are as happy and healthy as they can be.”

When SBS sits down with the park’s manager, Paige Sinclair, to discuss the accusations against her business and the death of baby Ji, it’s clear the backlash against has taken its toll. But the 62-year-old Canadian, who has lived in Coffs Harbour for 25 years, is defiant.

“I’m a great animal lover and it’s important that in my duty of care, my custodianship, that I make sure these animals are as happy and healthy as they can be,” she says. “These animals have been here, some of them, for many, many years and cannot be released. And unfortunately the idea of sea pens in my opinion is not a good outcome for them.”

“We can’t control the water quality [in a sea pen], we can’t control the weather, we can’t control who’s going to feed them [or] who’s going to look after them.”

Paige Sinclair says the park is a vital tourist attraction in Coffs Harbour.

The campaign against Ms Sinclair’s business dates back to 2014, when Australia for Dolphins complained to the Department of Primary Industries that the park was in breach of the NSW standards for exhibiting dolphins. The group claimed two pools at the park were too small for the number of dolphins being kept in them. The Minister for Primary Industries, Katrina Hodgkinson, inspected the park and the department investigated but concluded that the main pool was the correct size and gave the second pool an exemption. Furthermore it said the rides and kisses were not in breach of the standards.

However SBS can reveal that while the department sent one of its staff members to inspect the park, it did not seek any independent veterinary advice about the condition of the animals or the environment, and relied on evidence from Dolphin Marine Magic’s own vet. It also relied on a survey of the pool sizes conducted by the park and did not obtain its own assessment.

Australia for Dolphins has refused to accept the findings of the investigation and referred the matter to the NSW corruption watchdog ICAC after it was revealed the minister’s children swam for free with the dolphins during their visit. The minister denied any wrongdoing. ICAC chose not to investigate.

It’s not only Australia for Dolphins the park has been dealing with. Earlier this year, a woman chained herself to the park’s show pool to protest the keeping of dolphins in captivity. When staff intervened to try and remove her, she allegedly bit a staff member. Last week, a man allegedly rang the park a number of times and verbally abused the staff members who took the calls. The incident was reported to police.

Aside from Ms Sinclair and two senior staff, none of the employees at Dolphin Marine Magic would speak on the record to SBS for fear of being targeted by people against the park. But off the record, staff recounted stories of workers being harassed and threatened around town and at social events – including teenagers who work at the park as casuals. They claim there is a small but vocal minority in the community who are determined to shut the park down.

The fight to end marine mammal captivity extends far beyond Australia’s shores. A number of countries have either banned or are in the process of banning the keeping of dolphins and whales in captivity, including Switzerland, Hungary, Chile, India and the United Kingdom. Finland recently announced its last dolphinarium will close.

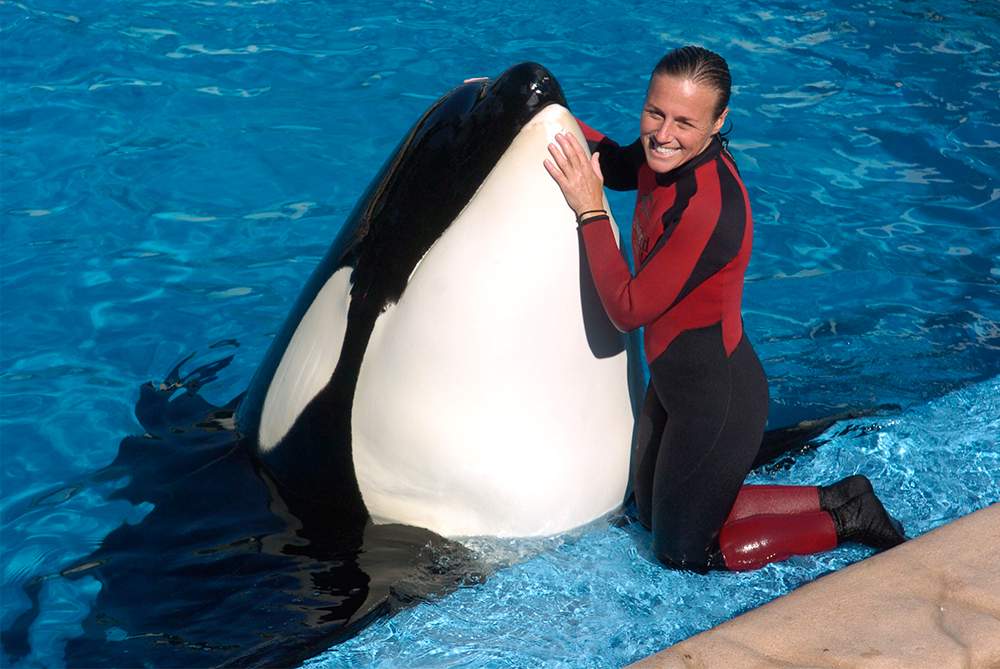

In the United States, the multi-billion dollar SeaWorld franchise became the target of public anger and scrutiny after a 2013 documentary Blackfish exposed conditions inside the park leading up to the death of trainer Dawn Brancheau during a live performance with a killer whale in 2010. The film revealed how Ms Brancheau, a 15-year veteran with the park, was the third person killed by a male killer whale named “Tilikum”, who was captured from the wild in 1983 and kept in cramped conditions in a Canadian park before being transferred to SeaWorld Orlando in 1992.

Dawn Brancheau was one of the most senior trainers at SeaWorld in Orlando.

Video shot by guests at one of the park’s Dine with Shamu shows – where people watch a performance while eating dinner at an open-air restaurant – showed Ms Brancheau playfully throwing fish into Tilikum’s mouth before lying on a platform in the water next to the whale, who was meant to mimic her action by rolling over. Instead, Tilikum unexpectedly pulled Ms Brancheau underwater and held her there, thrashing her about with violent force. An autopsy report revealed that Ms Brancheau's scalp had been torn from her head, she had a spinal injury and her left arm was bitten off below the shoulder. Her cause of death was listed as “drowning and blunt force trauma”. SeaWorld later put it down to “trainer error”, blaming Ms Brancheau for wearing a ponytail.

Sea World Australia, on Queensland’s Gold Coast, was affected by negative publicity generated by the film, but was quick to note the two parks have nothing to do with each other – Sea World Australia is spelt as two words and SeaWorld in the US as one – and are not tied financially. However, the two are involved in plans for a joint move to open multiple ocean parks in Asia together.

Sea World in Australia is owned by Village Roadshow Theme Parks, which also owns Movie World, Wet’n’Wild, Australian Outback Spectacular and Paradise Country. When SBS contacted the company asking for records of visitor numbers to Sea World before and after the release of Blackfish, a spokesman sent back combined visitor numbers to all of the company’s theme parks. Village Roadshow’s 2015 annual report revealed that visitor numbers to all the parks were down, but did not specify figures for Sea World, despite having done so in the past. When SBS asked for a record of Sea World’s visitor numbers alone, the spokesman repeatedly refused, stating: “The attendance figures are reported as a theme park group and not by individual park.”

Following the release of Blackfish, US SeaWorld went into damage control, launching a $15 million campaign to counter the claims presented in the film. The campaign included a website called “SeaWorld Cares” and a video series called “The Truth is in Our Parks and People,” in which it defended animal captivity and promoted its rescue and research work.

The extent of the damage to US SeaWorld is still being revealed, but if a 2015 financial report is anything to go by, public appetite for its brand of animal theatrics is shrinking fast. The net income in the second quarter dropped from $37.4 million in 2014 to $5.8 million in 2015. The report cited “continued brand challenges” as one of the reasons for the decline. Visitor numbers also took a hit.

In March 2016, CEO Joel Manby announced the company would stop breeding killer whales and focus on animal conservation. Following the announcement, the company’s stock rose more than 20 per cent. SeaWorld declined to comment when contacted by SBS.

The walls of Stanley “Hec” Goodall’s Coffs Harbour home are lined with paintings of dolphins and rows of books about the ocean. As the 88-year-old makes his way slowly from his front door to his lounge, there is only a narrow walkway for him to move between stacks of mementos from a life spent with marine mammals. Even his toilet is painted with images of dolphins.

As the Australian equivalent of famed dolphin trainer Ric O’Barry – who pioneered the industry in the United States and trained dolphins for the “Flipper” TV series – Mr Goodall started Dolphin Marine Magic, then called Pet Porpoise Pool, in 1970. Mr Goodall says he got his first taste for training dolphins after a chance encounter in the 1960s at a Tweed Heads dolphinarium, where he had been hired to paint some murals.

“In my spare time I started playing around with the dolphins after hours,” he says. “I found they were pretty clever and you could train them. I got a ball and I started playing around with them and we trained the dolphins to play basketball.”

When the park closed in the late 1960s, Mr Goodall opened his own operation, now known as Dolphin Marine Magic. “[It was] pretty primitive I suppose you'd say,” he says of the early days. “We were limited for funds.”

“The place has just turned into a greed-driven damned enterprise now. And all the charity work we used to do, or most of the charity work, has gone out the window.”

In the decades following, the park became a popular tourist attraction in the area, but Mr Goodall claims he was “pushed out” of the business in 2004 when the board decided he needed to be removed to make way for a new management. Mr Goodall is still the major shareholder in the company, but doesn’t have the numbers to take control back.

“I’m very disappointed with [the park]... it’s changed,” he says. “The place has just turned into a greed-driven damned enterprise now. And all the charity work we used to do, or most of the charity work, has gone out the window.”

He says his main issue is that the park “overworks” the dolphins and causes them stress. “They do two shows a day, three times in holiday periods, and they've always got people in the pool swimming with them,” he says.

But Ms Sinclair rejects that accusation. She says the dolphins perform on a rotating roster with regular days off, and most importantly, they enjoy it. “Our animals need enrichment and they just can’t be not doing anything,” she says. “It’s like putting a Kelpie in a backyard.

“The work that they do is what gives our guests the greatest pleasure; the ability to inspect, connect and touch and then possibly change their behaviour at their homes when they go home.”

Ms Sinclair says the park’s financial situation has also been misrepresented. “The park is a commercial enterprise and in order to for us to look after these animals we have to make money. [But] we don’t make a lot of money. There are people out there who think we make squillions of dollars. We don’t – we barely break even.”

And she is at pains to highlight the park’s rescue and rehabilitation work.

“The research work that we do is very important. A lot of it is to help the animals in the wild to start with. It’s not about just doing research for no good reason, it’s about why whales strand and why dolphins do this and how baby dolphins learn to vocalise, etcetera.”

“Dolphins are not endangered. There is only one reason to deliberately breed wild animals and that’s to make money.”

For decades, scientists and marine biologists have been warning that captivity can have adverse health effects on dolphins and will never match their natural environment.

Professor of the Cetacean Research Unit at Murdoch University in Perth, Lars Bejder, says dolphins, particularly the Indo-Pacific bottlenose that are kept at parks like Dolphin Marine Magic, have very complex social and family dynamics that can’t be easily replicated.

“They are one of the ones we know most about, that species,” he says on the phone from Perth.

“They live in what is a really highly complex social system. In the wild they grow to about 50, 60 years of age and throughout their lives they change in their social dynamics through to the different age categories. And that’s one thing that really needs to be considered when you have these animals in captivity.

“Those social dynamics are so ingrained, meaning that if you put animals in captivity with a very odd composition, that can cause a lot of stress for the animals and can cause a lot of problems.”

In the 1980s, the Australian federal government convened a Senate inquiry into dolphins in captivity following pressure from environmental groups and animal welfare organisations. Its report, published in 1985, gave a damning account of the captive industry.

“Cetacea in captivity have suffered stress, behavioural abnormalities, high mortalities, decreased longevity and breeding problems,” the report stated.

It went on to state that while the Australian industry was not as bad as overseas dolphinariums, “the committee is nevertheless of the opinion that cetacea generally have paid a high price for the dubious advantages of captivity.”

“The committee concludes that the benefits of oceanaria in Australia for humans and cetacea are no longer sufficient to justify the adverse effects of capture for captivity.”

In NSW, the then-Labor government moved quickly to shut down the oldest and most outdated parks, with the expectation that the remaining park at Coffs Harbour would eventually be phased out as the dolphins died of old age. However, a loophole that allowed parks to keep animals born in captivity meant the park could breed existing animals to replenish the population, with fresh breeding stock brought in from rescued animals to keep the gene pool strong.

By 2010, Dolphin Marine Magic was contemplating expansion with plans to buy adjacent land and build bigger pools to house its dolphins.

“From very humble beginnings with less than five staff and 7,691 guests per annum, to over 50 staff, greeting now more than 90,000 guests, we have come a long way,” Ms Sinclair said in a 2010 interview with local news website Coffs Coast Focus.

“With the increased numbers of guests and the animals now nearing capacity, we will need to expand and grow even bigger and better in the near future.”

Australia for Dolphins CEO Sarah Lucas says the Senate report had no impact.

“More than 30 years later, Dolphin Marine Magic is still breeding these highly intelligent animals in chlorinated tanks, and is not making any efforts to phase out dolphin captivity,” she says.

“Dolphins are not endangered. There is only one reason to deliberately breed wild animals that swim hundreds of kilometres a day in the wild into tiny, chlorinated tanks – and that’s to make money.”

But Ms Sinclair says that position is based on an ideological quest to remove all animals in captivity and ignores key facts.

“My team are feeling very vulnerable to bullying and harassment from people who do not understand what we really do,” she says.

When asked if she believed the campaign will continue, she lets out an exasperated sigh.

“Absolutely! Do you think they are going to stop?”

Coffs Harbour locals seem largely unmoved by the campaign to shut the park.

In late 2015, a plan to place advertisements against dolphin captivity on two billboards came undone after the billboard owners were tipped off about the campaign’s message and refused to take part. And when Australia for Dolphins placed anti-captivity ads on the sides of two buses in early 2016, there was a strong reaction from the local Chamber of Commerce and other supporters of Dolphin Marine Magic. SBS understands the bus company refused to renew the ads for a second time as requested by the group.

Local MP Andrew Fraser says the park is an invaluable part of the local economy and its closure would be a huge blow to business.

“The economic benefit to Coffs Harbour is something in the vicinity of $20 million per annum, and they are figures done by Southern Cross University,” he says.

Ms Sinclair admits the park will lose money next year because of a slump in visitor numbers but blames the Global Financial Crisis, not the campaign against the park.

“It’s not only a great tourist attraction that employs local people, but it educates locals and overseas people in marine mammals. So to shut it down, to me, is just nothing but a group of people who don’t live in Coffs Harbour.”

But visitor numbers and the park’s annual reports, which show a steady decline in profits from around $370,000 in 2008 to just $30,000 by 2014, hint at a different story.

Ms Sinclair admits the park will lose money next year because of a slump in visitor numbers but blames the Global Financial Crisis, not the campaign against the park.

“Since the GFC, our numbers have gone down, but that’s a trend that’s happening in our area at this particular point in time, even with the visitation to hotels and motels,” she says.

“The other thing is, for the first time in Australian history since the GFC, people are not spending the money that they used to and they’re not going out to spend money that they don’t have to.”

At odds with these claims, official visitor numbers for the NSW north coast region show an increase in the past two years, with overnight visitors rising 2.4 per cent in 2015 and 6 per cent in 2014 on previous years.

The park in Coffs Harbour has been open for 46 years.

Australia for Dolphins says the legislation seeking to ban dolphin captivity in NSW is a stepping stone to shutting down Sea World in Queensland and abolishing the practice across the country.

Adding weight to the group’s cause, in April 2016 the RSPCA released a definitive statement outlining its position on the issue.

“The needs of cetaceans held in captivity cannot be met,” the statement said. “Dolphins, for example, are highly intelligent animals with complex social families, as well as specialised attributes. Their natural life is to roam the oceans, so restricting them to pools or tanks severely inhibits their normal behaviour as well as their ability to swim naturally.”

The RSPCA cited studies showing dolphins in captivity “may suffer stress resulting in appetite loss, ulcers, and increased susceptibility to disease due to changes in their social grouping, competition over resources and unstable social structures.”

Jordan Sosnowski believes Australians hold a similar view.

“It’s clear the public are starting to turn away from marine parks so regardless of whether you're for or against dolphin captivity the park is eventually going to close,” she says.

But Paige Sinclair says marine parks will stay relevant as long as they continue to bring joy to families, despite flagging numbers at her own operation.

In correspondence with SBS following our interview, she sends through a log of visitor comments, recorded by people leaving the park, as proof.

“When I am having a bad day or need something to brighten up my day, I read what the people who love us have to say,” she says.