Is enough being done to provide culturally appropriate

services to male perpetrators?

Research has revealed that mainstream family violence services are falling short in dealing with male perpetrators from non-English speaking backgrounds, especially refugees.

The gaps in the services are leaving families in the lurch.

Marty Smiley takes a look at behaviour change programs geared towards men from culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia for The Feed.

“When I started this work. There was a sentiment in the family violence sector that we shouldn’t work with perpetrators,” Hala Abdelnour says.

"But working with men ultimately protects women and children.”

Hala Abdelnour knows what perpetrators of violence are like, she regularly sits in a room with them. It’s her job to listen to them, to challenge them on their behaviour.

Since 2016, she’s worked with over 500 men in male behaviour change programs, the main form of intervention available to men who use violence against women.

The men that undergo these programs have often financially, emotionally and or physically abused their partners. Men often labelled as ‘cowards’ and ‘monsters’ are the centre of Hala’s work.

“Working with men in men's behaviour change programs is more challenging than working in a maximum-security male prison because the conversation is specifically about gender with men who use violence against women,” Hala says.

“And I’m the only woman in the room.”

It’s a daunting role. A role many tell her they’re glad they don’t do.

“People have yelled at me, made rude comments and even attacked me for my choices. I cop a lot of judgment.”

“As a society, we’re quick to wipe our hands of people who seem too hard to deal with”

This reluctance for doing the work is something Hala has often witnessed in the family violence sector. In particular, a fear of working with men from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD).

Late last year, a report commissioned by the Victorian Multicultural Commission, and written by Hala, was released. The report showed non-English speaking men - particularly refugees - are being left behind by family violence services that aren’t catering programs to their experiences.

It’s something Hala says ultimately harms victim-survivors and families.

As part of the report, Hala conducted 83 consultations across 52 organisations in the family violence sector.

Most of the participants in the study stated they had ‘never accessed or been offered training on applying family violence to culturally diverse communities or working within a trauma-informed capacity.’

“The reason for this is that mainstream organisations don’t represent the populations they wish to serve,” Hala says.

“The settlement services need more family training and family violence services. They need a total reform to be more inclusive of people from diverse backgrounds”

One case study included in the VMC report highlighted the issues CALD families face when engaging with services.

Mariam* arrived with her husband George* and two children in Australia on humanitarian grounds, as refugees, in early 2020.

Not too long after they arrived, living in a regional part of Australia, Mariam confided in her settlement worker that George had been physically violent towards her. He’d assaulted her in front of their children, and she was injured as a result.

Mariam’s settlement worker informed the police - although Mariam didn't know or understand the process that would follow.

George was excluded from the family home by police and ordered to appear in court.

Not long after, Mariam and George attended court where child protection representatives were present.

The local family violence project officer didn’t speak her language. Google Translate was used to try to explain Mariam’s rights and the processes she’d need to follow in court.

A Family Violence Intervention Order was issued and George was required to do counselling and complete a male behaviour change program. He would not be able to return to the home until the judge was satisfied that he’d engaged with the appropriate perpetrator services.

The VMC report indicated it was unclear whether George understood the conditions of his Order.

He was given six weeks to begin the Order, despite the wait time on male behaviour change programs being eight weeks.

When he returned to court, it became apparent George hadn’t completed the conditions of the Order. No one had contacted him to connect him with a behaviour change program or a counsellor.

It also became apparent that he was homeless.

The matter was deferred for another six weeks. This time, George was provided with an interpreter and a local male behaviour change program provider agreed to work with him individually via the interpreter.

He was taken to a caravan park to stay but upon arrival, he became fearful of the stray dogs nearby. Torture by dogs had formed part of his experience before he sought refuge in Australia.

Although George’s trauma had resurfaced, no other accommodation options could be found for him, so he remained there.

After six weeks, George was able to return to the home while still being required to continue the counselling component of the Family Violence Order.

Michal Morris, the CEO of InTouch, a Multicultural Centre against Family Violence, says these cases are common and often require cross-organisational collaboration.

“When there’s potential for risk, the perpetrator does need to be told ‘you can’t do this to your family'," Michal Morris says.

Although the case created acute stress and pain for the family, it’s a situation Michal believes wouldn’t have happened if the perpetrator made the choice not to use violence.

“The system did what it needed to do because it protected [Mariam*] and the children from harm. But the issue is that the system didn’t assist Mariam or George to understand what was happening and why it was happening. They weren’t taken on the journey and as result, it caused additional anxiety, trauma and harm.”

For many newly arrived migrants, a bad first experience with Australian services can be detrimental to their future and can influence their decision to access them ever again. This poses a risk to victim-survivors who may not trust the services they need to protect themselves and their family if violence reoccurs.

“If they don’t understand the options, they won’t make a choice and they may stay in an unsafe situation,” Michal says.

Highlighting the lack of quality services for CALD men who use violence should not take away from the primary focus of the family violence sector: the protection of women and children.

As previously reported by The Feed, CALD women also face similar barriers in accessing support from family violence services.

Although there is a lack of comprehensive, population-wide data on violence against women from migrant and refugee backgrounds, specific studies suggest high prevalence rates. There are also specific issues of complexity, such as partners using a woman’s temporary migrant status as a means of violence.

InTouch specialises in cases of violence within CALD families.

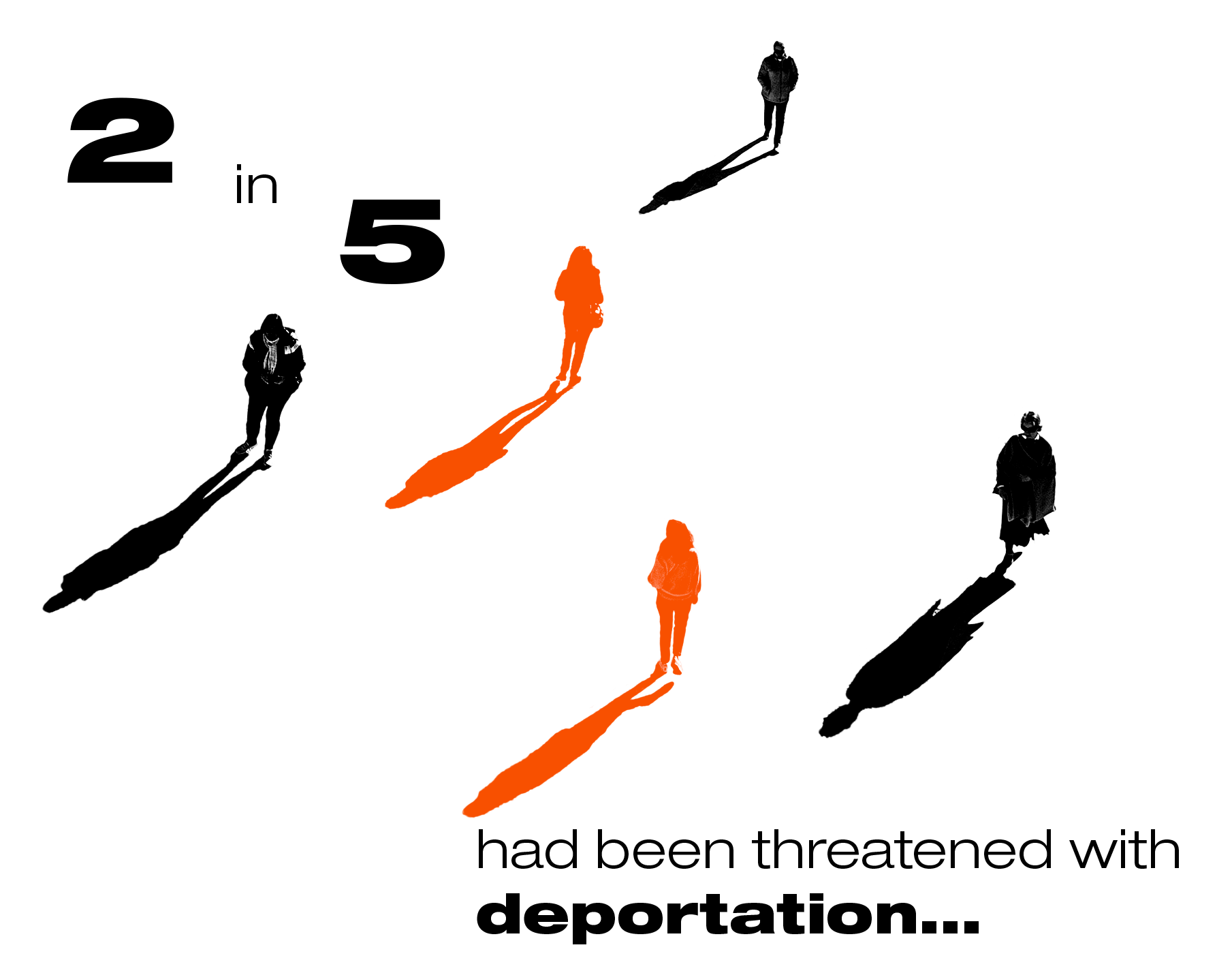

In 2017, researchers studied 300 of InTouch’s case files from women who sought support in 2015–16.

Of these women,

... 4 in 10 were threatened that sponsorship for their visa application would be withdrawn.

These factors could contribute to why CALD women are less likely to report family violence.

When it comes to the general population, according to data taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, between 2016-18;

Almost 10 women a day were hospitalised for assault injuries perpetrated by a spouse or domestic partner.

1 in 3 Australian women (34.2 per cent) experienced physical and/or sexual violence perpetrated by a man since the age of 15.

And 1 in 6 women before the age of 15.

How are family violence perpetrators dealt with in Australia?

In 2015, the Council of Australian Governments created the National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions. The main aim was to put perpetrator accountability at the centre of how agencies and organisations, such as the police, courts and the child protection system, deal with family violence.

Standards two and four of the National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions outline that perpetrator interventions should be designed to effectively respond to perpetrators from diverse cultures and communities.

Despite this, there are very few culturally specific programs for men who use violence in Australia, particularly outside of NSW & VIC.

Victoria has led the way in developing CALD perpetrator specific programs. Kildonan Uniting Care offers a male behaviour change program for South Asian Men (in-English) and an Arabic Speaking Men’s group. Relationships Australia offers a program for Vietnamese men. InTouch offers a pilot program ‘Motivation For Change’ with African, Afghan, and South Asian groups.

In NSW, Relationships Australia is now offering an Arabic Speaking Men’s group and recently started a Tamil Speaking Men’s group.

Where there are no language-specific male behaviour change programs for family violence, many mainstream services offer interpreters for the sessions.

Dr Khaldoon Fahmi works for Kildonan Uniting Care, a provider of family violence support and intervention.

Since 2018, he’s been the Facilitator of an Arabic Speaking male behaviour change program in Victoria.

He’s also worked in group settings where CALD men have an interpreter present as well as in one on one settings.

“Interpreters take time,” he says. “It can be very difficult that way.”

Prior to the course being adapted into Arabic, Fahmi observed that in group settings, men from CALD backgrounds contributed less than other participants noting that they would ‘nod, say yes or agree’ but not engage with the content so much.

“When we changed their group, the dynamic totally changed. It became more challenging for them,” he says.

“That doesn’t mean they agree with me on everything! But when they disagree, I can explore their beliefs and challenge them on the behaviour.”

This is a key distinction for facilitators of in-language male behaviour change programs.

“I know the tactics they use to shift responsibility and accountability away from what they have done.”

Often Fahmi hears his clients position themselves in relationships as a ‘protector’.

“They say they have a ‘responsibility to protect,’" he says.

“When they position themselves as the protector they are able to control.”

“That’s when I say ‘protection is different from support'."

It’s an idea that is not culturally specific, but in context, Fahmi can communicate in terms his clients can connect to.

It’s a patriarchal behaviour, it’s a behaviour of control.

It may manifest differently, but it’s still abuse.”

Settlement Services International (SSI) helps newly arrived migrants in practical ways to find their bearings in Australia. The organisation assists with airport pickups, short-term accommodation, community orientation and health assessments. It educates them on their rights, Australian values and the law.

Family violence awareness is not a part of that.

Many of the practitioners The Feed spoke with believe family violence awareness should be a part of information workshops run by SSI so that intervention can occur earlier.

Alongside male behaviour change programs, women and children advocates ensure the partners of the men are empowered and protected.

“By talking to the women, we can monitor whether the behaviour change program is having an affect,” Viji Dhayanathan says.

This year, Viji was a part of the Tamil speaking Building Stronger Families program as a partner support worker.

In an average week, she could be finding a refuge for a client, making a report to the police or helping a client obtain an Apprehended Violence Order. Other times she’ll help by finding babysitters or locating something they need or don’t know how to access.

“Many women don’t report because in their own countries they wouldn’t be listened to. Men’s actions are accepted.” Viji says.

“They need to understand that domestic violence is a crime and if it happens they should report it. Not just physical violence, but other forms of family violence and abuse.”

This is a crucial part of the partner support worker’s role: to make sure women understand their rights and where to get support if abuse or violence occurs.

Where Viji sees the system failing is when men don’t do any meaningful work to actually change their behaviour. Not all perpetrators are required to complete male behaviour change programs.

“Sometimes they’re given 200 hours of community service. How will that change their behaviour?”

Since the Victorian Royal Commision into Family Violence in 2015, Australia as a nation has come a long way in understanding the issue.

It’s been five years since the National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions were created and although new in-language programs are being developed, Hala hopes her report will move things along and bring attention back to the gaps in the family violence sector.

“In all honesty, I believe that migrant and refugee men won’t be too hard to work with when we as a sector get better at working together to support them."

“I’ve seen through my work at the Institute of Non-Violence that there is a growing appetite for improving equity and equality in access to services.

“I’d like to see that continue with stronger actions towards inclusion and cultural safety within the sector, backed by more effective funding structures.”

*Names have been changed

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or family violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit www.1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

Information on male behaviour change programs can be accessed via the Men’s Referral Service on 1300 766 491 or visit ntv.org.au