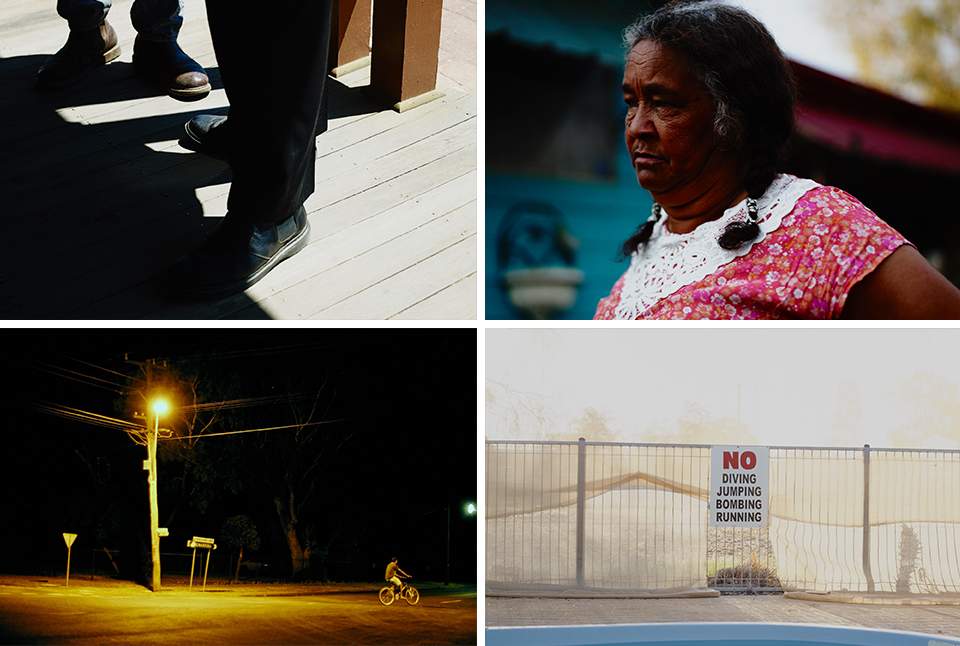

A hotbed of crime and violence. That's how Walgett was portrayed on the evening news. But what's really happening in this historic town, mentioned in Banjo Paterson's poetry? Why do the people of Walgett stay?

December 2, 2015

Infamy arrived for the tiny outback town of Walgett earlier this year when a blurry phone video of a girls’ classroom fight went viral on YouTube. A local high school, already in the dusty throes of renovating its classrooms, is now also rebuilding its reputation.

Walgett Community College’s 100 or so pupils now take their lessons in a temporary cluster of demountables.

Their town sits, like a comma, at the junction of the Barwon and Namoi rivers within a vast northern NSW floodplain which the past four years of drought has dried to weed and stubble, evaporating jobs and income. Its official population is 2300. Most are Indigenous, as are most of the schoolchildren.

Shown on evening bulletins, the phone video recorded a girls’ fight in the secondary school’s Year 8 classroom. Two girls aged 15 and 16 were arrested and charged with affray and intimidation. There were reports that violence had escalated and that police were patrolling the campus on foot.

The Sydney Morning Herald said “Walgett Community College a hotbed of ‘violence and criminal behaviour’”. Soon the humble town, home to the Gamilaraay people and the southern hemisphere’s biggest grain silo, was all over the internet and TV.

School captain Melissa Hayley, a bright Aboriginal 17-year-old with a bent for business, who has carved a pathway to university, knows how gruelling the pursuit of education can be for remote-area students. She found one patch of schooling tough.

“They don’t have the Walgett view of everything. They just accuse, accuse, accuse.”

“I got through it,” she says, relaxing amid the hubbub of a bustling birthday party at a modest bungalow just outside town, on the banks of the Namoi. Hundreds of caged pet birds squawk, music blares and running children squeal.

But she is not speaking of her Walgett school experience. Three years ago, a scholarship offer gave her a choice between her hometown school and another in the Queensland regional city of Toowoomba. They’re in the same nation, but worlds apart.

Walgett’s public secondary college caters almost exclusively to Aboriginal students, in a community where some children are so poor that they have had to steal food. Downlands, in comparison, is a private Catholic secondary school, set within lush parklands on a green hill in Queensland’s Toowoomba. A year of board and tuition costs about $38,000. Its tree-lined driveway, chimneys and white lace balcony railings, sometimes wreathed in Darling Downs mist, lend the campus an air of prestige and tradition. Those with the wherewithal can choose equestrian competition as a school sport.

Melissa chose Downlands and instantly regretted it. Overwhelmed by Toowoomba’s intimidating size, traffic, the judgmental attitudes of girls from comparatively privileged backgrounds, and the daily squeeze into blue-and red uniform frocks with hats, socks and leather shoes, she was so miserable that for two months she was “just ringing Mum up every night and asking to comeback…pleading”.

She missed “little old” Walgett, where some evenings the war memorial’s marble at the main roundabout – a statue of a soldier imported from France in 1923 – is the only human figure visible on the main drag. Apart, perhaps, from a handful of Aboriginal teenage boys kicking a football along the street, for something to do.

What does school captain Melissa Hayley think of Walgett?

“They don’t really have any contact sport up at boarding school where I was at – so it wasn’t good and the girls and me didn’t really get along,” Melissa says. “We had two different perspectives, but here, it just doesn’t matter; you could rock up in, like, your pyjamas and you don’t get judged by the girls.”

She believes the world has unfairly judged her chosen school. To her, the fight which caused the furore was not “that big a deal”. But the media followed up, with stories of brawls, of a 15-year-old girl allegedly threatening a fellow student with a brick, of teachers enduring regular verbal abuse, of chronic absenteeism and multiple suspensions.

“Classroom violence at notorious NSW school sparks calls for intervention,” proclaimed 9news.com.au. “Ice and alcohol addiction leads to rise in violence at Walgett Community College”, The Daily Telegraph headlined.

“They don’t have the Walgett view of everything,” Melissa laments. “They just accuse, accuse, accuse.”

She is among those who love the town, where locals face adversity with their own brand of rough-and-tumble, richly insulting humour, often using descriptions of body parts which would make sensitive souls quake.

When it comes to losing heads, Walgett Community College seems worse than the court of King Henry VIII.

Anne Dennis, a vocal critic of one former principal, is president of the local Aboriginal Educational Consultative Group (AECG). She counts 8-10 permanent principals since 1999. Add acting principals and those numbers double, she says.

Dennis knows what it is to struggle to get an education. She grew up in a tin hut on the banks of the Namoi and walked via the muddy riverbank to school.

“I remember one teacher slapping me across the face and calling me a ‘dirty little Aboriginal boong’,” she says. “It was the words that stayed with me.”

“My parents and grandparents were denied access to education. They weren’t allowed to go to school…My parents learnt themselves how to read by reading newspapers. And we’ve got a whole group of kids coming through today and they can’t read and write. To me, it’s quite devastating,” she says.

Dennis believes that during school hours, sometimes there are more teachers than students on the campus. Word about town is that some students deliberately misbehave so they will be suspended, while others don’t even bother with that strategy and simply habitually truant.

“When you start to see kindergarten students being suspended – and year 1 and 2 – you wonder what is happening,” Dennis says.

She complains that all principals arrive with the best intentions, but need locals, especially elders and parents, to voluntarily help them engage students. But locals also need to earn a living, she says.

Dennis wants elders and other community members to be funded so they can catch those who fall, teaching children about the riches of their Indigenous culture, in keeping with the state government’s own Connected Schools program.

“The funding usually goes into the school and then they deliver the same program, the same way,” she says. “To deliver the same thing and expect a different result is madness.”

A whole curriculum was developed to help engage Aboriginal people by the NSW AECG, Dennis says. It covered everything from spirituality to rivers to bush medicine.

“Yet we cannot receive the funding from state Government or the Commonwealth to implement [it],” she says.

Gamilaraay elder George Fernando

Anne Dennis and elder George Fernando, 81, walk along a potholed road at Gingie Reserve, 10km west of Walgett, to a hall whose walls are lined with murals depicting key moments in Indigenous history – from resistance to removal, to Paul Keating’s Redfern speech. School children painted them.

“We’ve offered this to the school to run classes here, particularly for students who are suspended. It’s got to be funded,” she says.

Excited young voices echo in the street, followed by loud clunks of rocks being chucked onto the roof.

But Dennis now concedes that not all of Walgett’s ills can be laid at the school’s door: “There are a lot of things that impact on the community and we have a tendency, I suppose, to blame the school.”

A dry-humoured motel owner reinforces this when excited young voices echo in the street late one night, followed by loud clunks of rocks being chucked onto the roof. The man chases the boys with dangerous toys away.

“Yeah, they learn it at school. The triangulation, the angle,” he jokes.

Walgett is rarely noted in the nation’s affairs, but it won an unsavoury reputation as a very frightening town, through the 1994 rape and murder of a nurse Sandra Hoare at the local hospital (by cousins Brendan and Vester Fernando).

She was 21. Her photo hangs in the foyer of Walgett’s most expensive building, the new $15 million police station.

Criminal defence lawyer Su Hely, who has been plying her trade in the adjacent heritage red-brick courthouse for 15 years, believes that horrific crime flavoured outsiders’ view of the town.

“That’s all I heard of before I came here all those years ago – you’ll get murdered out there,” she says. “And nothing could be further from the truth.”

“I would happily walk around this town, day or night, alone. I wouldn’t do that in Sydney.”

Hely has been involved in Children’s Court proceedings arising from the famous school fight.

“When I read the facts involved – and they shall remain utterly confidential – I thought it was a storm in a teacup. I thought, ‘this happens not only in Walgett. Why did the children of Walgett receive such unwarranted attention?’

“The kids I come into contact with are fabulous young children,” she adds. “The only problem in Walgett, which is a problem in all small towns… there is a lack of resources here. There are not things for kids to do.”

Homegrown rugby league stars Ricky Walford and George Rose are very much alive, but Walgett may be better known for those who have passed on. The late, great Aboriginal singer Jimmy Little lies in Walgett cemetery, his black gravestone shining amid humbler burial sites marked with small white crosses, often featuring the flag of the departed’s rugby league team.

During the 1990s, Walgett endured a torrid era of drunken violence. It was a place where angels fear to tread.

Aboriginal teenager TJ Hickey, whose death sparked Sydney's Redfern riots of 2004, was buried here in his hometown amid furious allegations that his fall from a bicycle was the result of a police chase.

The Aboriginal people here have historically suffered cruel losses of family and culture, having been trucked from reserve to reserve, forbidden to speak their languages and even, until the 1960s, to enter the township.

They have been crucial workers in the area’s rural industries, including cotton. In good times, the area is a rich source of livestock and grains. Some call it the chickpea capital of Australia.

During the 1990s, Walgett endured a torrid era of drunken violence. It was “a place where angels fear to tread,” according to Gary Trindall, who worked then as a NSW Police community liaison officer. This seems to have lodged more firmly in the national consciousness than the town’s attributes.

Some think the violence was rooted in tribalism, with different clan groups warring, says Trindall.

"We don’t see people walking down the street, off their faces and going ballistic."

“It was nothing to be standing in this main street here [as] two or three coppers, with 500 to 600 people fighting around us, Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights,” he says. “Now, it’s quiet… You could fire a shotgun up the street of a night and you wouldn’t hurt anybody.”

But he worries that the drug ice has hit town. NSW Police local area commander Jim Stewart says, “I’m not going to deny it’s here. It’s everywhere. But we don’t see people walking down the street, off their faces and going ballistic.”

Both Superintendent Stewart and a local court official confirm Su Hely’s assertion that Walgett is not a serious crime hotspot.

“I don’t want to give you the impression that there’s no crime here, because there is – and that it’s not a problem, because it is,” says the court official. “But I think it’s a town that’s been maligned more than it deserves to be.”

In her caseload for the week, domestic violence, affray, drinking and assault charges figure are at the top end of the crime spectrum.

“There’s nothing to do here,” she says. “The drought’s killed work, so people drink. And they get violent.”

On the other hand, she points out that representatives of the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) office, which handles serious matters, only visit for an average of two matters in any given month.

“Crime here – it’s low level,” the court official says. “Narromine is much more violent than this place is.”

People are often arrested for unlicensed driving, for riding a bike without a helmet and for offensive language. Affray charges are the big ones for Children’s Court.

“It’s usually girls fighting,” the official says. “It’s generally offensive conduct that it gets boiled down to. It’s to do with boys. And it’s not that bad. It’s not that much.”

“If I had a big problem here, I’d have a really big kids’ court and I don’t at all,” the official says.

Superintendent Stewart says policing juveniles in Sydney’s Mount Druitt was tougher work than Walgett. Most juvenile arrests in Walgett are for property crime, such as malicious damage, but the numbers are low. And there is a distinction between criminality and bad behaviour, he says.

“The kids that we deal with here are different, in terms of better…because they don’t get exposed to the things that happen in the city,” he says. “We can manage them.”

“Yes, there is bad behaviour. But you tell me where there isn’t bad behaviour anywhere around. You go anywhere, western suburbs, eastern suburbs of Sydney, Wollongong… Newcastle, it’s the same thing.”

Police try to talk to children, to turn them back before bad behaviour escalates into crime. And here, they get to know kids and families.

"Many break-ins by children are related to what they can get in the fridge."

“We are part of the community,” he says. “That’s the big difference I see here, with our police.”

In some homes, there are no role models to set them on the right path. In others, no food. Many break-ins by children “would be related to what they can get in the fridge,” Superintendent Stewart says.

As for the secondary school, he says, the stepped-up police patrols following the outcry in April have dropped back to routine levels.

It’s a hot Friday afternoon. The local pool is packed with squealing children. On the back streets, Walgett locals stick to the asphalt road, avoiding the crunch of spiky brown burrs on parched footpaths. They often carry the thin ends of gumtree branches as switches to swat the fierce posses of small, sticky flies.

In a corner of Walgett’s secondary school grounds, three girls and a boy armed with buckets of water-bombs are fighting, running, yelling. A girl calls to the boy, “Hit me with your best shot.”

But no-one’s getting hurt. It’s a game at the PCYC, supervised by local youth case manager Senior Constable Cheryl Hoffman. Once everyone is saturated, she yells: “Ceasefire!”

“It’s safe and it’s harmless and everyone’s just having a good time,” she says. “I think that’s why they enjoy it, because it’s safe and they’re safe here. So, if they have any issues they can come to us and sort it out.”

This is almost the only place older children can go after school to enjoy organised activities, including high-energy trampolining. Some who frequent the PCYC are case-managed after being referred by police or other authorities, as a way of diverting them from criminal behaviour, while others simply drop in for the fun of it.

“I’ve been running movies once a fortnight with the girls, so they’ve got a bit of time to themselves without the boys around and we make bracelets and paint nails and just do girlie things while we watch movies,” Hoffman says. “It gives them somewhere to go on Friday nights, so they’re not out on the streets, bored.”

“All kids are good kids. You’ve just got to find out what they’re good at and focus on that,” she says.

“It only takes one kid with a can of spray paint to impact a whole town.”

Walgett Shire Council’s community development manager, George McCormick, says: “It’s unrealistic to think that young people are just going to not go on the streets. We don’t have a mall. We don’t have a games room. We don’t have all these other things that people in the cities take for granted.”

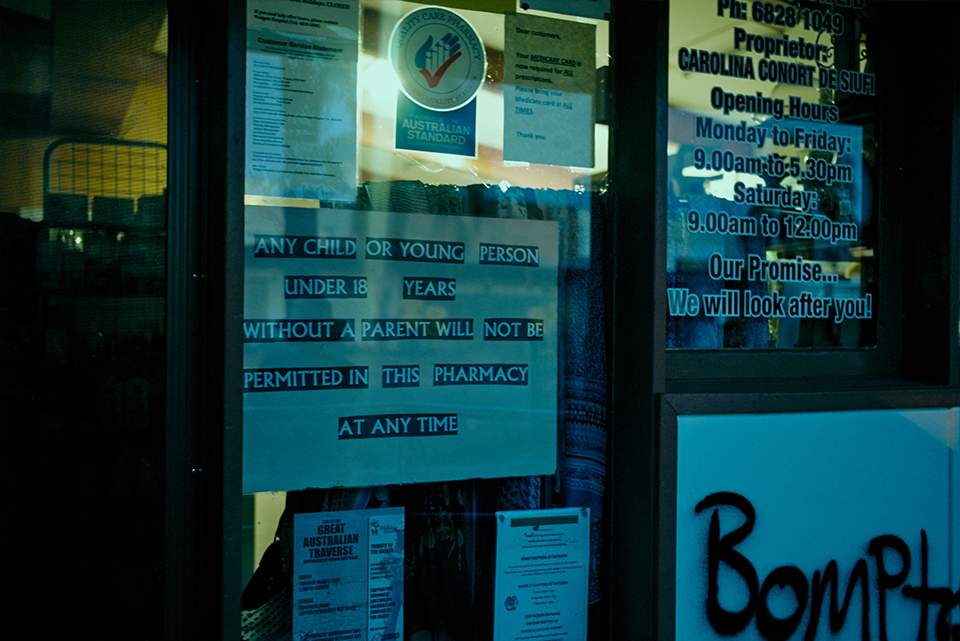

The library welcomes children, but some shops are off-limits. Walgett Pharmacy repels with a sign: “Any children or young person under 18 years without a parent will not be permitted in this pharmacy at any time.”

Some children feel safer on the streets than at home, because of domestic violence, McCormick says.

“That’s right across the board,” he adds. “We’re not special.”

Off limits for kids: sign and graffiti on Walgett's pharmacy

“Wherever there’s generational disadvantage, generational welfare dependency, lack of employment – all those negatives – the flow-on effect can be negative and a lot of it can be that domestic violence side, unfortunately.”

“Through all that, what resilient people,” he says. “Amazing.”

In a small town, little is hidden in the back streets like in the city, McCormick says: “There’s lots of good stuff going on. However, it only takes one kid with one can of spray paint to impact a whole town within half an hour.”

Many small businesses have bars or mesh over their windows, a hangover from Walgett’s wildest days. Although groups of children take to the streets every night once the air cools, during SBS’s week-long visit, the wildest main street event is a gumtree chorus of raucous galahs.

At the shire’s Walgett Youth Centre, primary school children run around with balloons tied to their feet, bounce balls, or muck about with a bank of computers.

For some, this is not just the end of the week; it’s the end of primary school. In final term, they face tough choices. Sarah Weatherall, 11, is one. She thinks she will take up the scholarship offered by an Armidale school.

“Mainly I want to get out of this town,” Sarah says. “There’s too many cheeky people up there, at the high school… They swear at me and all that.”

But when her aunt, Trish Weatherall, suggests the local school is on track now, she agrees she could try it for a year.

A non-Aboriginal mother who has lived in Walgett for five years, says that she has to leave town because the Department of Family and Community Services has said that a child she fosters should not attend the local high school.

“She’s not like the kids out here,” the mother says. “They’re a lot tougher. She’s a bit too gentle.”

The locals’ upbringing has toughened them up, she says. “It’s the way they talk to each other. For them, they’re all over it, whereas she can take it too personal.”

“I like that respect I get from the kids and teaching them and being with them and just helping them to stay out of trouble”.

Nicholas Tedin, 17, a youth worker who has completed his HSC at the local high school, says he grew up seeing some friends take the wrong path – and “getting caught up in silly stuff”, such as rock-throwing and window-breaking.

“That sort of thing leads on and becomes bigger and bigger,” he says. [It] becomes a lifestyle.” But whatever has happened at Walgett High only amounts to “just little fights and arguments”.

As one of the budding politicians on the Walgett Youth Council, he thinks he can divert children from crime.

“I like that respect I get from the kids and teaching them and being with them and just helping them to stay out of trouble,” he says.

On Friday night, Fox Street has a buzz. People throng around the competing fast food joints: Walgett Gourmet and Wong’s Fish and Chips. The strains of “Stuck in the Middle with You” and the bright voices of 20- and 30-somethings pour from the Oasis Bar.

At the bowling club, under floodlit beams filled with shimmering white bugs, excited children cavort on a green. Inside, babies, grandmothers and teens are dressed to the nines for an 18th birthday party. An iced blue-and-white cake with “Eels” scrolled across it is carried through the bar.

A wall mural adorning Vinnies in the main street depicts happy people in a green landscape, with the words “Life can be soooo good. Live it!”.

Nearby, three boys throw palm-tree droppings at a crushed can on top of a small metal bollard. One finally hits the can and cheers. They’re living it, Walgett style.