This Friday marks the 20-year anniversary of the day the East Timorese people voted overwhelmingly for independence from Indonesia after a 24-year occupation.

Another significant anniversary comes next month, on September 20. That was the day of the arrival of the , the Australian-led multinational force that brought an end to the violence that wracked Timor-Leste after the independence vote.

In the intervening three weeks, in the violence, which had been orchestrated by the Indonesian military and its proxy militias. Over 250,000 were forcibly displaced to West Timor and some 80 per cent of the infrastructure was destroyed.

Many Australians are rightly proud of their contribution to Timor-Leste’s independence, which served as an historical corrective to Australia’s longstanding support for Indonesian’s invasion and forced integration of East Timor in 1975-76. The more than in the INTERFET mission marked the nation’s since the Vietnam War.

Yet despite the goodwill the mission engendered in Timor-Leste for the Australian people, relations between the two nations have repeatedly been undermined by contentious negotiations over control of the lucrative oil and gas fields that lie in the Timor Sea.

As Prime Minister Scott Morrison prepares to travel to Dili for the anniversary this week, Australia-Timor-Leste relations finally seem to be back on track.

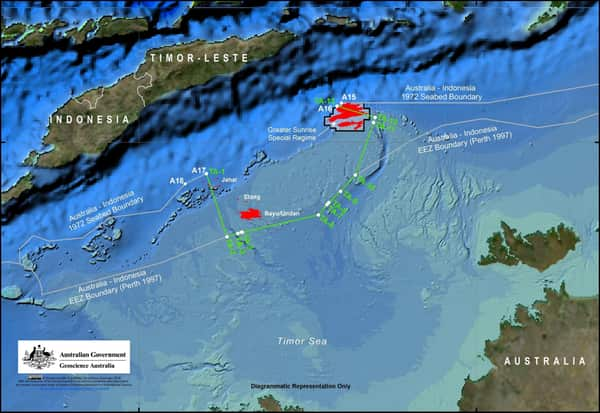

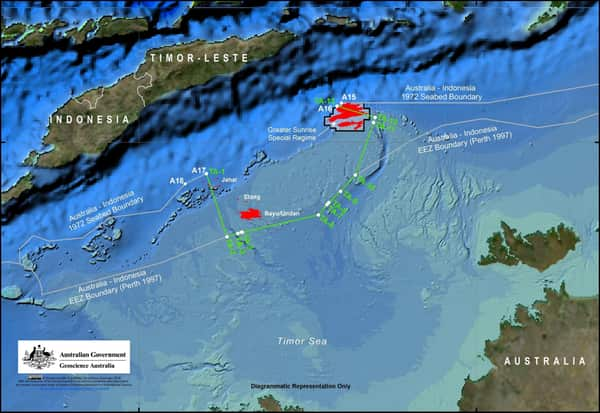

A created a permanent maritime boundaries between the two states for the first time. This border is widely expected to following its ratification by both parliaments – another momentous milestone in Timor-Leste’s young history.

Australian soldiers conducting an operation to flush out militia fighters in Timor-Leste in September, 1999. Source: Jon Hargest/AAP

Conflict over oil and gas

Since its independence, Timor-Leste’s relations with Australia have been overshadowed by one major factor: the oil and gas fields on its contested maritime border.

Relations hit rocky waters in 2012 when Timor-Leste challenged the , which had been signed by the two countries in 2006. This a 50-year moratorium on maritime boundary negotiations, or five years after exploitation of the Greater Sunrise gas field ended, whichever occurred first.

Allegations then emerged in 2013 from a former ASIS agent (now known as Witness K) that during the negotiations over the CMATS treaty. This led Timor-Leste to in The Hague challenging the treaty for want of good faith.

Australia was embarrassed by the exposure, but determined to maintain the countries’ ongoing treaty arrangements and focus instead on revenue-sharing agreements. However, Timor-Leste argued that the bulk of the oil and gas fields in the Timor Sea would lie on their side of a median line and pushed for a permanent boundary to be drawn between the countries.

As relations deteriorated, ministerial visits ceased for almost five years.

Because Australia had abandoned the international courts as a means of resolving the maritime boundary in 2002, Timor-Leste had only one option left. In 2016, it of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) compulsory conciliation process: a non-binding but mandatory mediation between nations on maritime disputes.

The conciliation panel of five judges the CMATS treaty’s moratorium on defining a maritime boundary was invalid. This dealt a fatal blow to decades of Australian foreign policy focused on maintaining its continental shelf claim in the in line with the .

Australia could have attempted to tough it out since the tribunal’s finding was non-binding. But by this point, the Labor opposition was the maritime boundary with Timor-Leste should be renegotiated in line with international law, putting additional pressure on the government to resolve the dispute.

A separate dispute over China’s claims in the South China Sea, , made Australia’s position increasingly untenable, as well. The world was urging China to respect an international tribunal’s maritime ruling, so it would be difficult for Australia not to do the same.

A new boundary finally set in the sea

Once the UNCLOS opening decision came down, the two sides began negotiating a border in good faith. against Australia in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, and , without Australian objection.

Announcement of the new maritime border treaty followed in March 2018. It was a major diplomatic breakthrough and soon led to the resumption of ministerial visits. The treaty created a median-line boundary in the former Timor Gap, placing the wells in the former (JPDA) in Timor-Leste’s sovereign waters.

The treaty created a median-line boundary in the former Timor Gap, placing the wells in the former (JPDA) in Timor-Leste’s sovereign waters.

The new maritime boundary between Australia and Timor-Leste. Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Timorese believe there is another A$1.5 billion of oil reserves in this area, but as these fields near the end of their life, the greater game lies in the as-yet-untapped Greater Sunrise field. This field straddles the eastern side of the new boundary and is believed to be worth in .

Timor-Leste also achieved a from the future development of this field, up from 50 per cent under the CMATS treaty to 70-80 per cent, depending on whether the pipeline eventually goes to Timor or Darwin.

China’s potential role in development

Since then, Timor-Leste’s focus has shifted to negotiations with its commercial partners over its ambitious plans for the Tasi Mane oil and gas megaproject on its southern coast.

This project could bring additional challenges for the relationship with Australia. The East Timorese government estimates that external financing will provide some per cent of the estimated US$10.5-12 billion funding for the project. And Timor-Leste’s ambassador to Australia has already that if funding partners cannot be found among Timor-Leste’s friends in Australia, the United States, Japan or South Korea, then Chinese capital would be a clear alternative.

Timor-Leste has that China’s Exim bank offered a A$16 billion loan to finance the megaproject, though it acknowledges both countries have expressed over the separate development of Timor-Leste’s petrochemical industry.

It is also notable that China this month donated some requested by the Timorese government.

Even though China might be seen as a for developing Timor-Leste’s oil and gas processing capabilities, Beijing’s involvement would certainly complicate relations with Australia.

Timor-Leste has generally sought to balance its relationships with key regional powers, in part to prevent the dominant influence of any single nation. The country’s foreign minister recently emphasised that discussions on the Tasi Mane project are ongoing with potential partners in Australia, the US, Europe and Asia.

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop meets with her Timor-Leste counterpart, Dionisio Soares. Source: AAP

Remaining obstacles to closer ties

Despite the major improvement in bilateral ties between the two countries, there are some remaining points of contention.

The prosecutions of Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery in the espionage whistleblower case have been criticised by former Timor-Leste leaders Xanana Gusmão and Jose Ramos-Horta. This week, Gusmão to give evidence on behalf of the two, raising the potential for further embarrassment for Australia.

Some political activists in both Australia and Timor-Leste have also called for Canberra to it has received from the JPDA since the border treaty was signed in 2018, and accused Australia of delays in ratification.

While these accusations have made headlines, Timor-Leste’s parliament had not ratified the treaty either until last month. In any case, Timorese NGOs point to the far larger question of in revenues that Australia has received dating back to 2002, when revenue-sharing agreements began.

But it appears there is no appetite in either country to consider repayment of historical royalties.

As Australia and Timor-Leste prepare to celebrate the anniversary of the independence referendum – as well as the recent restoration of good bilateral relations – it’s worth keeping in mind that new hurdles potentially lie ahead, with implications for the wider region. Michael Leach has previously received funding from the Australia Research Council.

Michael Leach has previously received funding from the Australia Research Council.