Australian companies are selling munitions and military technology to war-torn African countries under a Defence Department plan that critics have branded “grotesque” and unethical.

Worldwide, defence officials approved the sale of an estimated $5 billion worth of military equipment in 2019/20 - more than the typical yearly export value of Australian wine, wool or wheat.

The government is trying to ramp-up the sale of military equipment under an ambitious plan to make Australia a global powerhouse for defence exports.

Documents obtained under Freedom of Information laws show the Australian government has approved military sales to at least 18 countries in Africa since 2015.

This includes Burkina Faso, where state forces are accused of executing hundreds of prisoners, and Uganda, where the government is accused of secretly diverting weapons to South Sudan.

The Defence Department has also approved sales to Zimbabwe, where the government is suspected of abducting and torturing political opponents, and Eritrea, the so-called “North Korea of Africa” which has been ruled for decades by a totalitarian dictator.  Former United Nations lawyer Melissa Parke, who was also a Federal Labor minister, says Australia is trashing its reputation by selling munitions and military technology to countries accused of gross human rights violations.

Former United Nations lawyer Melissa Parke, who was also a Federal Labor minister, says Australia is trashing its reputation by selling munitions and military technology to countries accused of gross human rights violations.

UN forces in the Central African Republic, which is in the grips of a violent civil war. Source: EPA

“I find it hard to believe that, rather than seeing ourselves on the international stage as a good global citizen, that instead we would seek to increase the manufacture and sale of weapons that cause death, injury and destruction to people who've done us no harm,” she told SBS Dateline.

“The UN arms trade treaty was something the Australian government claimed as an achievement during its time on the UN Security Council.

“But since that time, it has increased arms exports, including to countries accused of war crimes, while decreasing transparency about those exports.”

'Inherently lethal' technology

The international market for weapons is extremely lucrative, and Australia has grand plans to become a major exporter of military equipment.

“Our ambition is to be in the top 10 defence exporters in the world, in the future,” then-Defence Industry Minister Christopher Pyne announced in 2018.

Munitions and military technology are typically manufactured and exported by Australian companies.

However, the government plays a crucial role in the process - sales must be approved by the Defence Department in the form of a “defence export permit”. Australia’s military sales are notoriously opaque. The government refuses to release specific details on what equipment is being sold, or who is buying it.

Australia’s military sales are notoriously opaque. The government refuses to release specific details on what equipment is being sold, or who is buying it.

Former Defence Industry Minister Christopher Pyne wanted Australia to be a top 10 military exporter. Source: AAP Image/Lukas Coch

Defence exports are broadly sold under two categories - the "munitions list", and the "dual-use list".

Category 1 permits - or the munitions list - covers equipment that is designed specifically for military use or equipment that is “inherently lethal” – and includes ammunition, missiles, guns and tanks.

The Defence Department says the munitions list also covers equipment such as explosives, radios and training equipment.

Category 2 permits cover technology that meets civilian needs, but can also be adapted for military uses.

Since 2015, Australia has approved 14 Category 1 permits to sell military equipment to Burkina Faso and 18 Category 1 permits for Uganda, Defence Department documents show.

There have been 14 Category 1 permits approved for the Central African Republic, which is currently in the grips of a violent civil war, and 6 approved for Sudan.

Australia has also granted Category 1 permits for sales to Angola (7), Nigeria (10), Egypt (11), Ethiopia (5), Sierra Leone (1), and Zimbabwe (1).

Category 2 permits have been approved for Eritrea (2) and Burundi (2).

A separate dataset provided by the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms indicates the government has also approved permits to sell arms to Zambia, Botswana and South Africa.

The Defence Department says it considers human rights and regional security before allowing Australian companies to sell weapons and military equipment overseas. Figures indicate very few sales permits are ever denied.

Figures indicate very few sales permits are ever denied.

Violence is escalating in Burkina Faso, where government troops fight running battles with armed insurgents. Source: AP

Amnesty International campaigner Nikita White says the Australian government appears to do little, if any, tracking of arms exports once they leave the country.

“There are a number of conflicts occurring on the African continent where there is a real risk of human rights abuses resulting from arms being used in those conflicts,” she told SBS Dateline.

“There are also a number of governments where we are approving export permits, which have a long history of cracking down on any and all forms of dissent – often quite violently.”

Sales to countries accused of using child soldiers

The documents show Australia has also been selling military equipment to Somalia, Mali, Libya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan.

The US Department of State in June this year singled out the governments of these countries for allegedly recruiting child soldiers.

Grace Arach was just 12 when she was abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army - a violent group of Ugandan insurgents - and forced to fight as a child soldier.

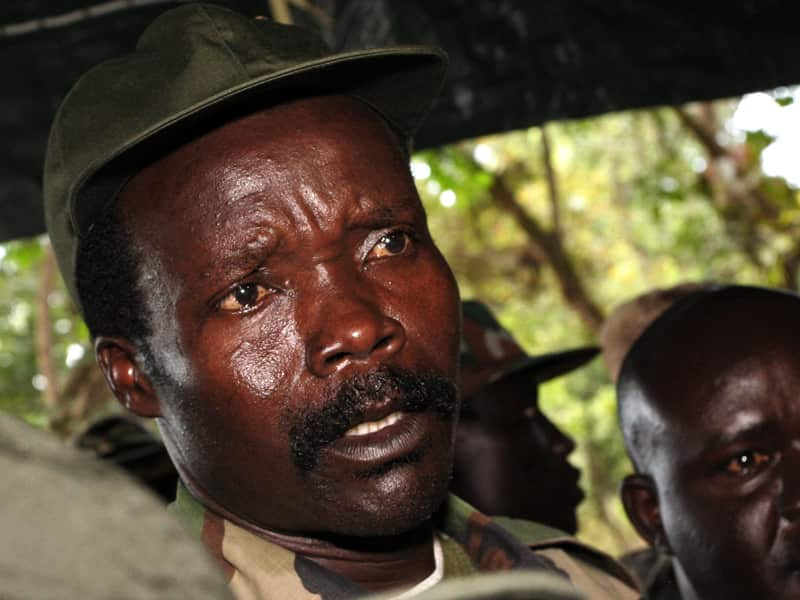

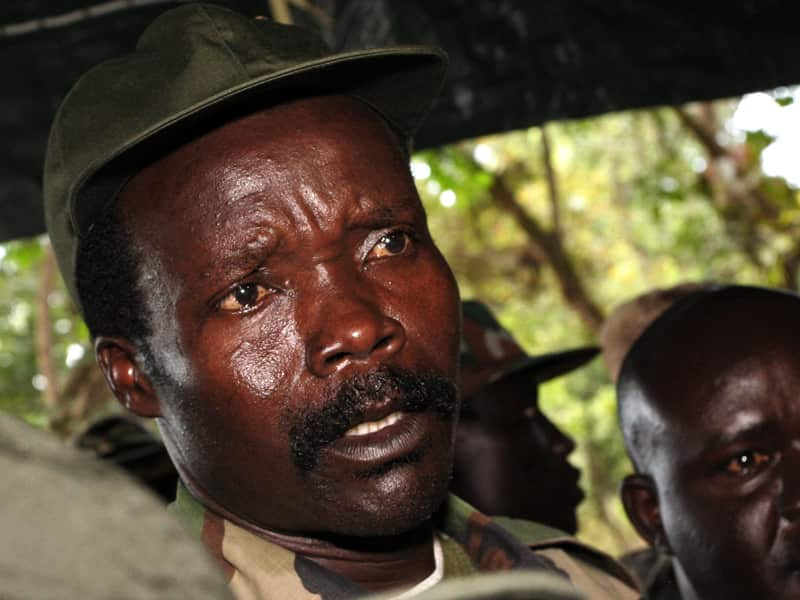

After she was abducted she was forcibly married to an LRA leader, who was the second-in-command at the time to war criminal Joseph Kony.

Joseph Kony’s LRA group was notoriously brutal and inhumane - abducting tens of thousands of children as slaves and child soldiers while terrorising Uganda and neighbouring countries between 1987 and 2009. During one LRA skirmish, Grace was shot in the chest.

During one LRA skirmish, Grace was shot in the chest.

Grace Arach was just 12 when she was abducted and forced to fight as a child soldier in a Ugandan rebel group called the Lord’s Resistance Army. Source: Supplied

“Because the bullet didn't go through my chest and it stayed in there - later on, my skin started peeling off,” she said.

“They tried two times to remove the bullets, and eventually they managed to get them out.”

Grace risked her life to escape the Lord’s Resistance Army in 2001, and eventually settled in Australia, where she is a specialist working with children who have disabilities.

Although Uganda is now more peaceful, she says the scars from conflict still remain, particularly for the tens of thousands of child soldiers forced to fight in the conflict. “Being a former child soldier, most times you don't have hope,” she said.

“Being a former child soldier, most times you don't have hope,” she said.

War criminal Joseph Kony, who led the Lord's Resistance Army as it terrorised Uganda. Source: POOL

“At the moment, in Uganda, the war is not active. But that doesn't mean that people are not suffering.”

Grace is now setting up a charity called Bedo Ki Gen, or Living With Hope, to help children move on from the trauma of conflict, and back into normal life.

“I would love to build a centre where children can come back and, and share their experience and feel safe - where they can come and get medical attention and counselling,” she said.

“Also serving as a champion to integrate the former child soldiers back into the community, which I think is important.

“I want to tell them that they shouldn't lose hope - you should always hope that tomorrow will be better.”

Amnesty International has linked the sloppy regulation of international arms sales with the recruitment of child soldiers in Africa.

“In Mali and close to 20 other countries, poorly regulated international arms transfers continue to contribute to the recruitment and use of boys and girls under the age of 18 in hostilities – by armed groups and, in some cases, government forces,” Amnesty has said.

Save The Children spokesman Mat Tinkler said Australia needed to think carefully about whether such countries were responsible customers for military sales.

“Countries in Africa that have received permitted military exports from Australia have been involved in things like grave human rights violations against children,” he told SBS Dateline.

“Those are things like recruiting children to be soldiers in conflict.

“It’s really hard to know whether Australia is walking this fine line of being an arms manufacturer on the one hand, and upholding child rights on the other.

“We have real concerns.”

'Simply grotesque'

Australia markets itself to international customers using the Australian Defence Sales Catalogue, which reads like a giant K-Mart pamphlet of military capability.

Featured in this year’s catalogue are armoured vehicles, mortar systems, automatic assault rifles, and drones equipped to carry “lethal” payloads.

The Australian government’s Defence Export Strategy outlines how military sales will be scaled up. Controversially, it lists the Middle East as a “priority market”.

“The so-called vision for Australia to become one of the world's biggest arms exporters is simply grotesque,” former UN lawyer Melissa Parke said.

“The Australian government has even more appallingly nominated the Middle East, which is currently mired in conflict, as a priority market.” Australia has been condemned for selling military goods to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Australia has been condemned for selling military goods to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

A page from Australia's military sales catalogue. Source: Department of Defence.

There have been global calls to stop selling arms to both these countries, because of their roles inflaming conflict in nearby Yemen.

New figures obtained by SBS Dateline show the Australian government has approved 31 category 1 permits to sell weapons and military equipment to Saudi Arabia since 2015, and 92 category 2 permits to export to the United Arab Emirates.

In contrast, it has not denied a single permit to sell to the UAE, and has denied just five permits for Saudi Arabia.

Ms Parke recently served on a United Nations expert panel investigating the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

“Yemen is facing the world's largest humanitarian crisis, with more than 20 million people dependent on humanitarian aid just to survive,” she said.

“This is an entirely man-made crisis caused by the parties to the conflict, some of whom are receiving weapons from Australia.

“It is clear given the number of public reports about violations in Yemen, that no Australian involved in arms exports can claim to be unaware of what is going on in Yemen.”

Houthi rebel gunmen in Yemen. Source: Getty.

Calls for transparency

The Defence Department says a "comprehensive process of risk assessment is undertaken before export permits are issued".

"The assessment considers contemporary information and takes into account factors such as the nature and risks associated with the goods and how they relate to risks associated with the destination and end-user," the department said in a statement.

"This assessment draws on specialist advice, as required, to provide a contemporary basis for decision-making.

"Permits are refused where risks are assessed to be contrary to Australia’s national interests, including the risk of use to commit or facilitate serious abuses of human rights."

Asked whether Australia tracked what happened to its weapons exports once they were sold, the department said "Australian legislation does not have extraterritorial application".

"Defence does not comment on individual export decisions, assessments, goods or customers in order to protect confidential commercially sensitive information and sensitive information used to assess the risk of the export," the department added.

Transparency campaigners say Australia lags behind other countries, who are much more open about their weapons sales.

“We really know very little about what Australia exports, where the exports go and how they're ultimately used. That’s quite deliberate,” says Elise West, from the Medical Association for the Prevention of War.

“We don't know which countries Australia exports to and if you request information from the government about exports, all the information within it is completely redacted.”

Australia needs to be more transparent, particularly to demonstrate it is meeting international obligations, Ms West said.

“Transparency is important because Australia has both domestic and international obligations that relate to arms exports - when approving exports, Australia has to consider its obligations under the Arms Trade Treaty, for example.

“But we don't know who makes these decisions, and what information is used when the decisions are made.

“It follows that being able to scrutinise these processes and decisions more fulsomely would help us be satisfied that what we are doing is either responsible, or not responsible.”