Insight finds out; how can your attention impact your life and can you change it? Watch on Tuesday August 31 at 8:30pm on SBS or On Demand.

In 2021, there were an estimated 28,300 people living with younger onset dementia in Australia. This is expected to rise to 29,350 people by 2028 and 41,250 people by 2058, according to .

Professor Julie Stout, of Monash University, has spent over 25 years researching neurological disorders. Recently, she’s focused her attention on early onset dementia, also known as younger onset dementia, and found through her work with patients that they are struggling to get the support they need.

Professor Stout said the problem starts with obtaining a diagnosis, which takes on average around three to three and a half years to receive.

“You have this long diagnostic process where people are losing ground at work, or they are having problems at home, they might be having relationship problems, all sorts of things are going on and yet they don’t really know what’s wrong,” she told Insight.

But the issues don’t end after diagnosis.

“Because of the complexity of their disorder getting care is difficult because usually dementia care is provided in the aged care sector but these people are not old so it doesn’t really fit for them,” she said.

“It leaves them with this problem where they have to navigate this intersection of the health care system which isn’t very familiar with their disease and the disability services sector which really isn’t designed for them.” Kate Swaffer was diagnosed with a rare, younger onset dementia at the age of 49. She told Insight in 2020 that when she sought support, the advice was grim.

Kate Swaffer was diagnosed with a rare, younger onset dementia at the age of 49. She told Insight in 2020 that when she sought support, the advice was grim.

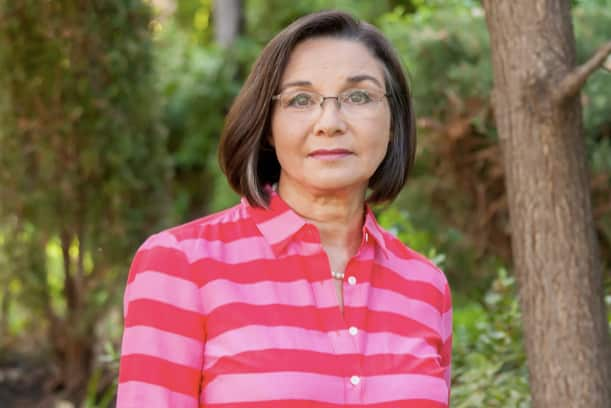

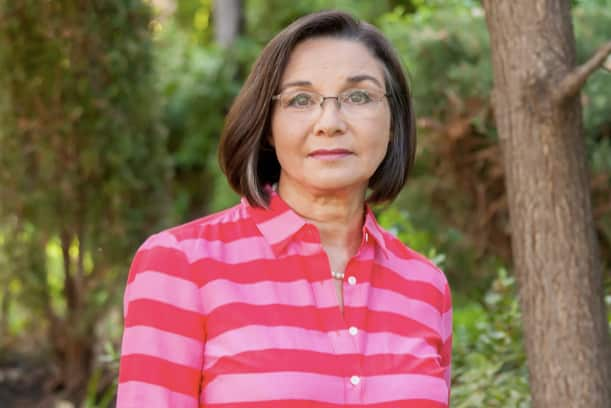

Dementia support advocate Kate Swaffer. Source: Meg Hanson Photography

“I was advised to ‘give up work, give up my studies, get my end of life affairs in order, and to start going to aged care respite a day a month to get used to it’, which I ultimately termed ‘prescribed disengagement’,” she wrote in .

“My husband was also advised he would soon have to give up work and take over all of my care.

“Whilst well intended, this advice gives way to a deep sense of despair, and a sense of hopelessness for any future, whilst also increasing the dependence and disabilities of the person with dementia earlier than necessary.

“Dementia is the only condition I know of where people are told to prepare to die, rather than to fight for our lives.”

Professor Stout, along with others in her field, are undertaking a range of projects designed to improve the current support systems that people with early onset dementia are faced with.

“We’re trying to find ways to improve the quality of life that people have, to make it easier for them to navigate the systems, to reduce the stress on families.”

“You can either help people navigate the system better or you can make the system more navigable but what you don’t want is high levels of distress and a high level of care-giver burden.”

Professor Stout said she is confident things will improve as collaboration between patients and experts increases. As for a cure, she said time will tell.

“I think it can be done with time and more research. No cures for any of these diseases yet exist, but there is huge investment by pharma in developing therapies that may yield significant treatments for young onset dementias.”

“We in the field think these will start paying dividends.”