TRANSCRIPT

Eating disorders have long been seen as a women's health issue - in particular, one that mostly affects young white women and girls.

But of course, like any mental health problem, eating disorders don't discriminate based on gender or race.

In fact, more than one third of those affected by an eating disorder are male, according to Australia's national organisation for eating disorders - the Butterfly Foundation.

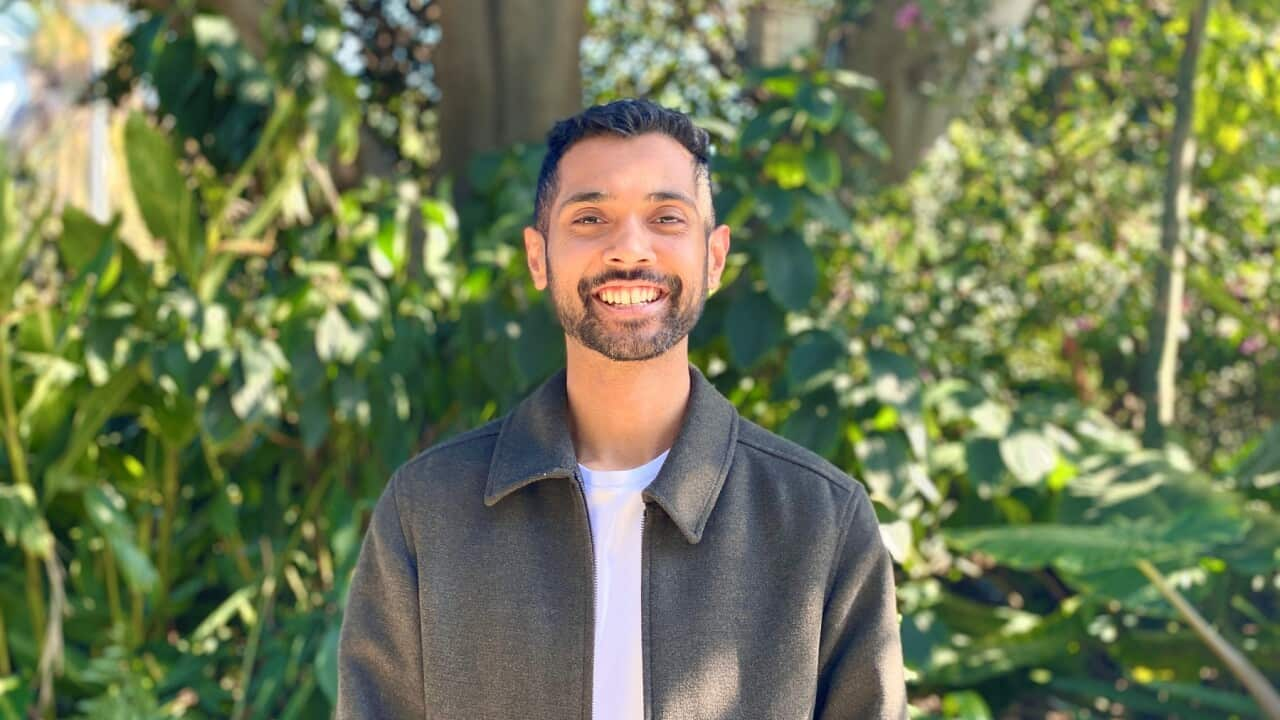

It took 30-year-old Tharindu Jayadeva a whole year before he sought help.

He says he didn't feel he had the right to have an eating disorder, despite noticing a deteriorating relationship to his body and food during the transition between high school and university.

“It was a really tricky time for me. I remember hearing all of these voices in my head around what I should be eating and what I shouldn't be eating, what I should be focusing on, and I didn't quite make the connection that it was an eating disorder or anything to do with body image at the time. The common narrative, whenever I did see things around or conversations around eating disorders, mentioned in the media or online, was that it was usually young women and young women who didn't look like me, of course. And so the main thing that I thought about was, okay, what I'm experiencing is something that I shouldn't be, I don't deserve to be experiencing this, which also means I probably don't deserve to be accessing some sort of support.”

Mr Jayadeva says this was the first time he experienced an eating disorder, but it certainly wasn't the first time he experienced unhealthy feelings about his body.

He says as a person of colour, he can recall feeling like an outsider in primary school, and even began restricting what he ate as a child.

“I remember when I was in primary school, there was a time where one of our teachers was giving stamps to all the students for good work. I remember lining up, put my hand out, and the teacher said that I didn't deserve a stamp because it wouldn't show up on my skin. And I think that was the real moment for me where I thought, well, of course I don't look like any of these other kids. And at the time I just felt like that was, yeah, that's normal. That's just me. It's my job to do something about it and to fit in.”

The Butterfly Foundation says men are four times less likely to receive a diagnosis for an eating disorder.

Clinical Psychologist and Manager at the Butterfly Foundation's National Helpline, Sarah Cox, says it's common for men to avoid seeking help.

She says less than 10 per cent of people contacting the hotline are men, despite the actual numbers of men with an eating disorder being a lot higher.

“There are a lot of misconceptions in society still around who can get eating disorders. I guess the misconception that only young women who are very thin might have an eating disorder, but we know that that's just not true and that they don't discriminate and can affect anybody regardless of gender, sexuality, cultural background, body shape or size. But I think because of those narrow portrayals, there can be a lot of stigma in society and a lot of self-stigma that people hold as well. So if they don't think that they fit that stereotypical presentation, they might just not even recognise that what they could be going through is an eating disorder.”

She says it's not just about gender.

“I think for people who have any sort of what we might call an intersection or identify with a characteristic that's outside of the majority or the stereotypes that societies hold, it kind of just adds extra layers of complexity and extra barriers and extra challenges in receiving culturally safe care.”

While there can be parallels with how eating disorders present across genders, men can also be more vulnerable to certain types of unhealthy patterns and behaviours.

Dr Zac Seidler is a clinical psychologist and Global Director of Research at Movember.

He uses a term 'big-orexia', which the American Psychiatric Association describes as a disorder characterised by a fixation on the belief that one is either not muscular or lean enough.

Dr Seidler says it's common among men for eating disorders to manifest in an obsession with muscle enhancement, steroid use and supplements.

“And so what happens is because of the way in which many men are socialised around pushing themselves around suffering and around pain, we've got all of these movements now around ice baths and all-meat diets, and it's just rife within the men's wellbeing space. And there is this notion of martyrdom that kind of comes with successful masculinity as it's thrown around. And so when they're using muscle-enhancing drugs, when they are showing binging and purging, when they are obsessing about fitness and body image, it's put in this bracket of he's an influencer. Look at him go, he's ripped, he's got all the girls, everything's going the way that it should. But underneath it, the psychological terrain that he's walking daily is fraught.”

He says the issue of eating disorders for men is much bigger than generally thought.

“And so I find it really strange that we've got this notion that eating disorders fit here in this feminised space when in fact I'm witnessing whether it's friends, colleagues, or more so within society and my clinical work. This is a huge, huge iceberg of an issue that we are only starting to cotton on to right now.”

Mr Jayadeva certainly felt that reluctance but says his cultural background added another layer.

“And so my background is Sri Lankan Sinhalese. We don't necessarily have language to talk about mental health. I think sometimes in my community and in my family, it feels like mental health is a luxury, and particularly around eating and access to food, that's a luxury for us. And to be potentially wasting food as you navigate an eating disorder, I think that was really challenging for me to have conversations about within my cultural context. And I think that added to the shame that I felt early on in my story too, where I felt like I was this kind of secret that we couldn't really talk about in my community, which is why it felt so easy to maybe separate myself from culture when I was accessing health mental health.”

The other issue is that a 'groupthink' can develop among men, as Dr Seidler explains, whereby a group of men all reinforce unhealthy ideas about body image and food.

He says a counter to this is fostering honest and meaningful male friendships that allow difficult conversations around mental health.

“If you can find a group of people who you can connect with and talk to about this stuff, you like to think that new information, new perspectives, are actually going to be safeguarding in many ways. So I think the one thing that is really awesome about male friendship is that we call each other out on our shit. That is the key to successful mateship, and that is what I hope for young guys who lean into these connections will do with their friends just as I would expect someone to do with me. It's that willingness to go, 'Hey, I've noticed this thing. What's going on there? Let's have a chat'. And there's no judgement. There's just a potential desire to work out what's best for him.”

Tharindu Jayadeva felt a sense of solidarity in finally seeing men who looked like him reveal their battles with an eating disorder and now he wants to help others.

“There were so many moments over the last 10 or so years where I thought I probably won't even be around to talk about this experience. And right now it fills me with hope, but also sadness, that there was a little TJ, a little Tharindu who felt that way. And I think that speaks to why I talk about it now - because there is a little Tharindu somewhere who just wants to hear and see someone who looks like him talk about these things. Because it might not be something their community talks about or family talks about but it is something that happens and it is possible to hold it in a safe and meaningful way.”

And if this story has raised issues for you or someone you know, you can get support from The Butterfly Foundation through 1800 33 46 73 - or via their website.