TRANSCRIPT

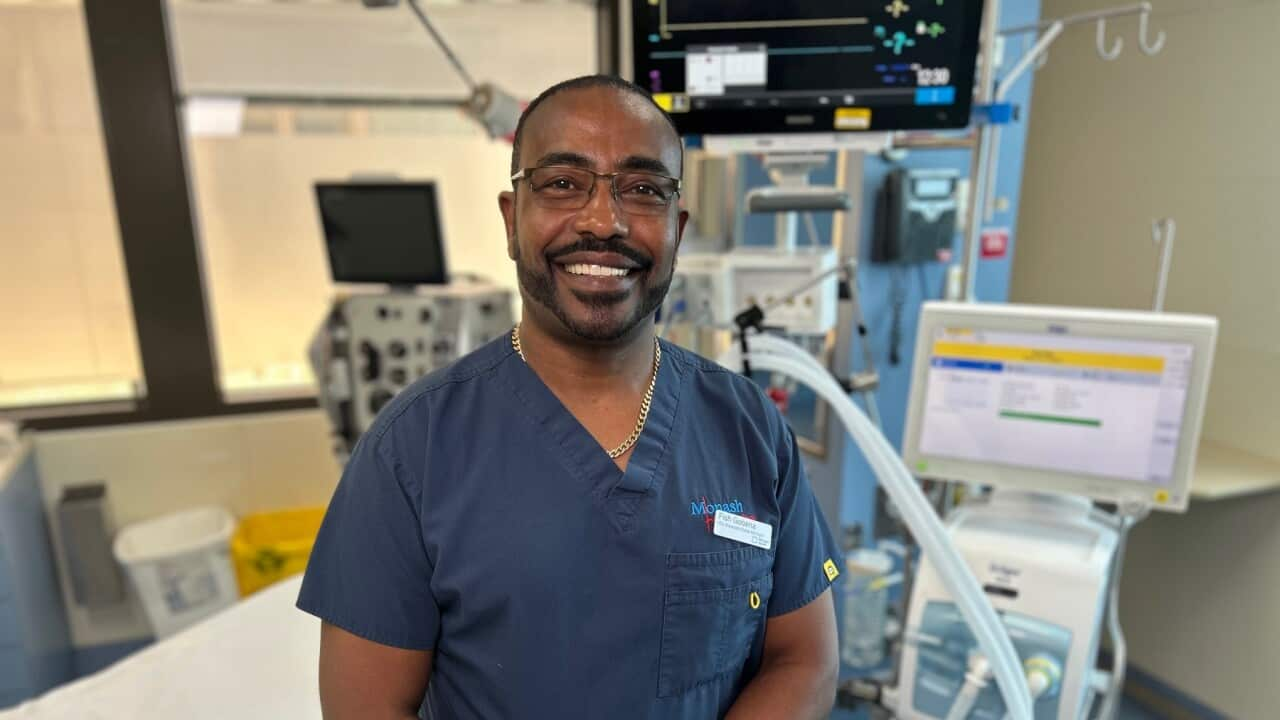

Fissaha Gobena – known to friends and family as ‘Fish’ – works in Monash Medical Centre’s intensive care unit.

It’s a tough job.

"It's very challenging. All the patients coming to ICU are very critically sick and we make sure the appropriate treatment is delivered to get the best outcome."

For the associate nurse unit manager, working on Melbourne’s medical frontline means staying calm under pressure.

And that’s where Fish excels, according to Intensive Care Unit Nurse Manager Adrienne Pendrey.

"I've worked with Fish for 17 years. When things are particularly hard in the unit, he is front and centre. And often if we need to troubleshoot a difficult procedure, we know that we can grab Fish, given his background and experience and working in adverse conditions."

Fish trained as a nurse in his homeland, Ethiopia.

He was born in the Oromia province and identifies as Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group.

After graduating as a nurse, Fish was sent to a town in western Ethiopia, joining a remote clinic with few resources.

"There was no medical equipment and very limited medication supply. We had to do what we can to save lives. Issues are a lot of infectious diseases. One of the big main issues is childbirth complications. Obstruction of a labour is quite common and so you need to use that equipment and they're very rusty, rusty enough to cause a lot of infections."

It was a tough start for a young nurse and the inevitable loss of life hurt him deeply.

"You see and watch and you cry, there’s nothing you can do. You get traumatised but it is a part of your life. I don't even know this different life until I get here and see the health system in Australia."

It wasn’t the only hardship he faced in Ethiopia.

Oromia has a long history of armed violence and social inequality.

Human Rights Watch has reported that ongoing fighting between insurgent and government forces have resulted in ‘serious abuses against Oromo and minority communities’.

"It's always there. All, it never stops. Still today things are getting worse, to the point kids are getting slaughtered. Regardless of whether you are involved in politics or not - being Oromo, you are targeted."

Fish fled his homeland after refusing to join the military medical corps.

"I've been forced to join the army as a nurse by my profession to go and help wounded soldiers. I could have been killed. I could have been killed or maybe to the minimum I could have just died in jail.

So, I got to Nairobi I got protection straight away by UNHCR. Fortunately my uncle has been living in Australia, he sponsored me and that made easy for me to travel to Australia."

Fish has built a new life here and is married to a Monash Medical Centre colleague.

And he is grateful to be raising their two children here.

"Living in Australia is heaven on earth. You are protected everywhere you go, you're safe day and night 24/7."

Fish also mentors young Oromos and other new arrivals.

But thoughts of the ongoing conflict in his homeland are never far away.

"There's a lot of refugees from Ethiopia to neighbouring country and there's no hope. Some of them are just dying because of the disease or malnutrition."

His care and concern for others makes Fish a valued asset in intensive care, says manager Adrienne Pendrey.

"I'm so proud of him. It's incredible to listen to his stories and what he's achieved coming from a background such as his and he gets on with his work, and is sort of quietly achieving all his impressive things as well as raising a family and being involved in the broader community. It's a credit to him and his resilience and passion obviously for the work that he's doing and a willingness to help improve people's lives."

As Fish approaches his 20th year at Monash Health, he dreams that one day Oromos in Ethiopia will also find peace.

"Just to live. Just to live as a human being. Just to live freely. They can work, they can do anything. Just freedom."