TRANSCRIPT

“Today is an amazing day. To be able to build on the work of so many of our people across countless generations, to be able to say that today we actually start the negotiations of treaty.”

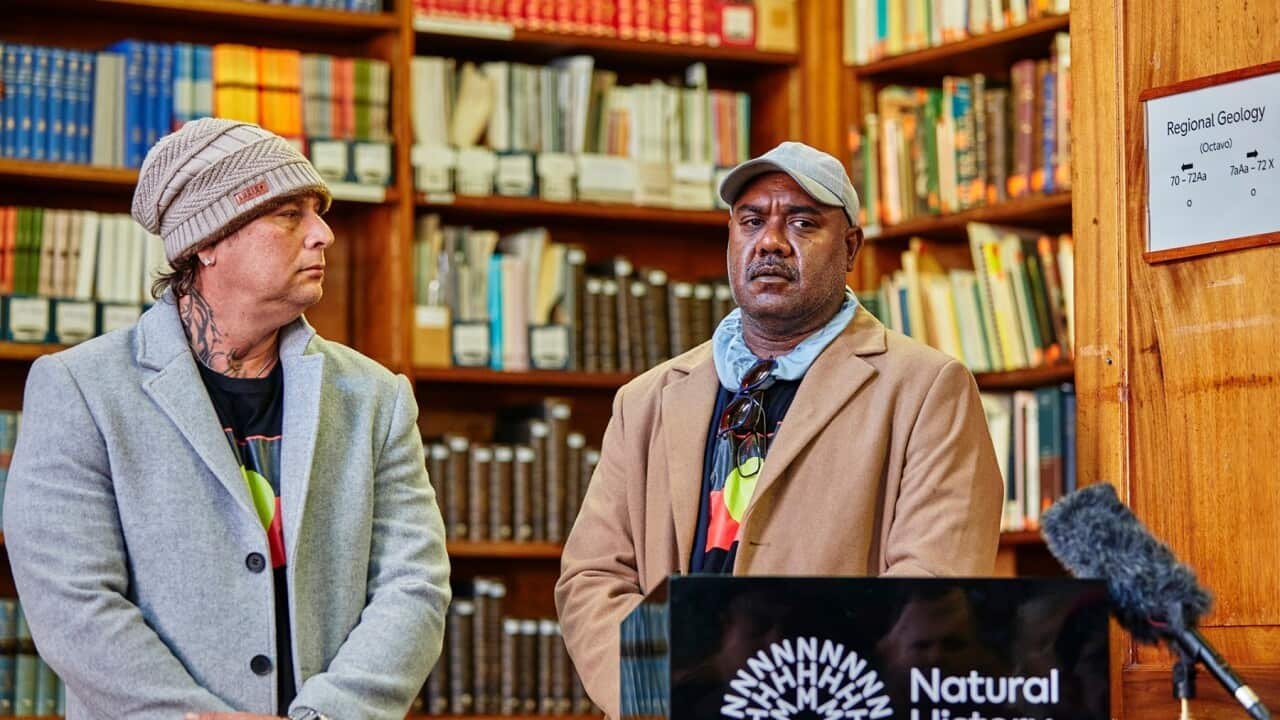

That's Reuben Berg, a co-chair of Victoria's First People's Assembly marking the next step in Victoria's journey to treaty.

Victoria's Premier has called it a historic day.

But Victoria's Minister for Treaty and First Peoples, Natalie Hutchins, acknowledges the process has been complicated.

“It's not been an easy road. It's been almost nine years of discussions, of arguments, of legislation through the Parliament.”

The Victorian Government committed to talking treaty back in 2016.

By 2018, Australia’s first-ever treaty law was passed in Victorian parliament setting a road map towards negotiations.

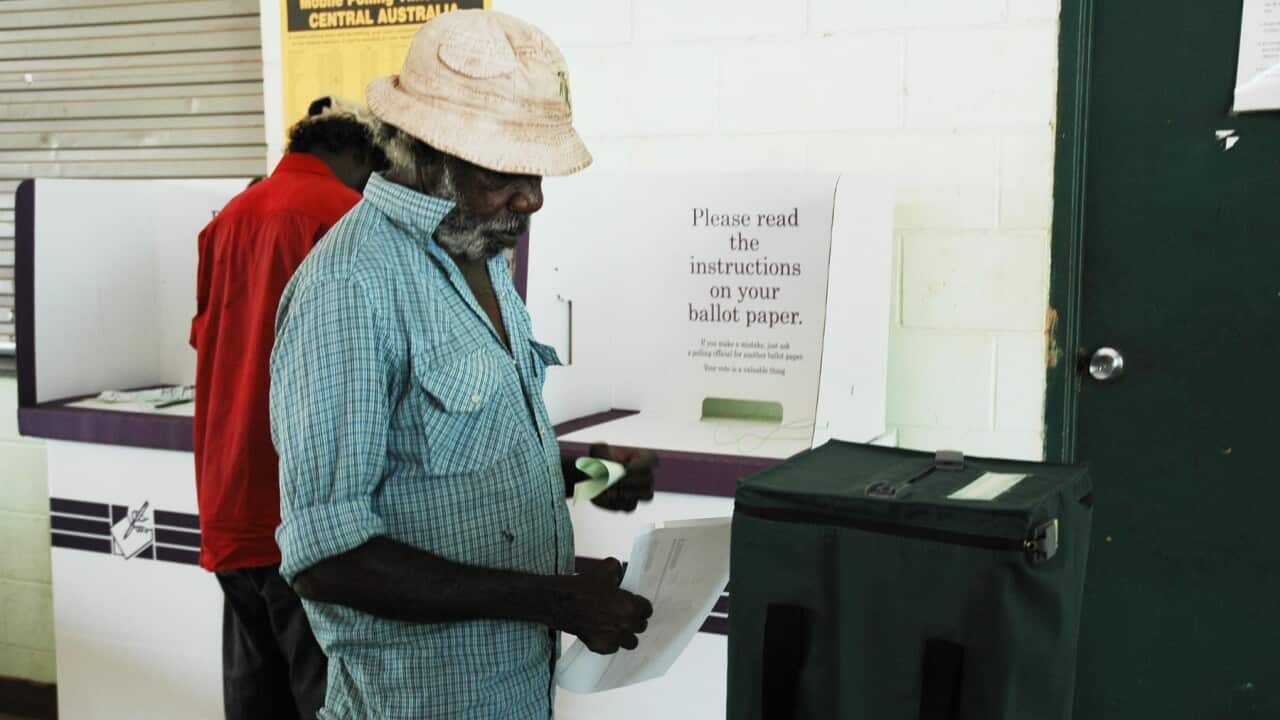

Part of that road map was the election of the First Peoples' Assembly, which was established in 2019.

Three years later, more legislation was passed to establish a Treaty Authority, which will now act as the independent umpire to oversee negotiations.

The First Peoples' Assembly says they will head into discussions with ideas underpinned by one principle: Decisions about Aboriginal communities should be made by Aboriginal people.

But before we get into the details, let's go back to basics.

So, what exactly is a treaty?

Dr Bartholomew Stanford, a lecturer in Indigenous politics from Griffith University, explains.

“A treaty in the Indigenous sense is a comprehensive settlement between the state and a traditional owner group. In that settlement, there will be things that cover land claims, recognition of prior ownership, access to land, potentially funding to support traditional owner corporations... they really can differ quite considerably based on where and when they're actually made.”

When it comes to why recognising ownership is important, Ngarra Murray, who is also a co-chair of Victoria's First People's Assembly, says you have to look to the past.

“We come from the people who have walked this land for over 60-thousand years, whose wisdom has sustained the earth, whose spirits rise with the rivers, whose songs are carried by the winds. It is our birth right to stand tall and walk proudly on this Country.”

She says a treaty will act as a bridge between the past and the future to restore the inherent rights of First Peoples.

Victoria's Premier Jacinta Allan agrees.

“Treaty is our opportunity at this point in our history to reset the relationship, to reset the relationship between the state of Victoria and the First Peoples of Victoria.”

So, what will Victoria's treaty look like?

A framework has been established to guide the process.

A key step in that journey will be expanding the roles and responsibilities of the Assembly, so it has meaningful decision-making powers when it comes to First Peoples' matters.

Reuben Berg, co-chair of the Assembly explains why.

“We know that when First Peoples have a greater role in things that affect them, we get better outcomes and that's what treaty is all about, making sure that we get better outcomes for our communities so that our future generations can thrive.”

The Assembly also wants to secure tangible improvements for Aboriginal communities right now.

Areas of discussion will include education, justice, health, land, housing, elders, and youth.

Specific ideas will include dual-naming to recognise Indigenous languages and a public holiday focused on First Peoples' history and cultures.

It's also important to note there will be more than one treaty.

In addition to the Statewide Treaty negotiated by the Assembly, various Traditional Owner groups across Victoria will be able to negotiate treaties specific to their Country.

Those negotiations will unfold over the coming years.

Treaty has long been deeply political in Australia.

In 1832, George Arthur the governor of Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, reflected it was "a fatal error" that a treaty had not been entered into with palawa* people.

He believed the absence of a treaty was a crucial and aggravating factor as to why palawa people experienced some of the worst treatment inflicted on First Peoples by British colonists.

In 1988, then Prime Minister Bob Hawke promised there would be a treaty with Indigenous Australians at Barunga Festival.

But since the Voice to Parliament referendum failed last year it has come under increased political scrutiny and attack by conservative governments and media.

Dr Stanford says the fallout from the outcome has been huge.

“Many of the other states and territories kind of put treaty discussions on hold while the Voice to Parliament referendum was happening and sort of waiting for the decision from the referendum, and we haven't seen much progress in those other Australian jurisdictions apart from Victoria post-referendum.”

Queensland was on track to formalise a treaty negotiation framework but with the elections of the Liberal National Party last month, treaty will be off the table for some time.

In the Northern Territory, there’s been no progress since the Territory's Treaty Commission lodged a report with government in 2022.

And the newly-elected Country Liberal government doesn’t support a Treaty, so it's also off the table.

New South Wales recruited Treaty commissioners earlier this year.

They’re now embarking on a 12-month consultation process before reporting back to government.

In Tasmania and the ACT, governments have committed to Treaty, but haven’t made any meaningful progress yet, while Western Australia has made no formal commitment at all.

Dr Stanford says there is just one other state that is showing signs of progress.

“The next state, which I would assume to make more advancements in this area would be South Australia because they have established their Voice to Parliament in that state. But in saying that, they've also seen some challenges this year.”

As to why treaty progress has been so slow in Australia, Dr Stanford says it comes down to the country's reliance on land-based economies.

“...You know mining, gas, form such a large portion of our economic output...That's why in this country we've also seen such strong opposition to Native Title and Land Rights more broadly because that poses a direct threat to our main industries, essentially.”

He says that makes the situation in Victoria unique.

“In terms of Victoria and the government's relations with traditional owners in that they seem to have a much better relationship, a relationship that's really aspiring towards collaboration and negotiation, which is quite rare here in Australia.”

It means Victoria will likely look to other countries for guidance and Premier Jacinta Allan says there are many good examples.

“The reason why we know treaty process works is because we've seen that internationally for decades now. For decades. Governments around the world, be they in the United States and Canada, in New Zealand, have had treaty with their first peoples and it's been shown to drive better outcomes.”

This year, the Victorian government invested 273 million dollars in First Peoples’ self-determination and support.

As for a timeline for the treaty, Premier Jacinta Allan says there's no specific date in sight.

“So in terms of the time that will take to finalise the negotiation process, it will take the time it takes to get it right. And that's what I think everyone should expect.”

The Premier has promised information will be provided to the public regularly throughout the process.

But ultimately, the government will make the final decision.

“At the conclusion of those negotiations, there will be legislation put to the Parliament of Victoria and it will be at that point that the Victorian Parliament has the moment to decide whether it takes the final historic step forward to enshrine Treaty in our state.”

For now, Reuben Berg, says entering into discussions with the Treaty Authority as a negotiator marks the start of a new era.

“So that unlike some of the discussions that have happened across the last 200 years where there hasn't been good faith, we're now moving into a space where there will be those good faith conversations and that gives our community hope.”

(*palawa: The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre tells us that the palawa people only use capital letters for people's names and family collectives)