Sometime later this year we’ll all be heading to the polls for the long-awaited referendum on constitutional recognition for First Nations people.

While the outcome remains unclear, the vote itself represents the culmination of more than a century of Indigenous activism. In an even larger sense, it is a struggle that goes back to 1788, when the fight to carve a space for Blak existence within imposed white law began.

Australia’s constitution makes no reference to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; there is also no mention of rejecting racism.

Those realities have allowed governments of all stripes to take Indigenous land and enforce punitive laws on First Nations people.

; nonetheless the work of countless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have believed in the cause deserves recognition.

Here’s a short history.

A new law(lessness)

The hundreds of distinct Aboriginal nations, each with their own strict laws, were seen as one homogeneous group by the invading British. Those laws, their sovereignty and their humanity were ignored by the colonists.

The British invasion of 1788 is wholly unaware and unconcerned with these laws. White law (or more often, lawlessness) begins its spread as Country is stolen from Aboriginal people.

This will be retroactively justified with , the lie that no Aboriginal sovereignty existed over the land.

White federation, Black deprivation

Corrolup Native Settlement in Western Australian saw many children of the Stolen Generations subjected to its horrors. The forced removal of children was the work of the state based 'protection' or 'welfare' boards.

Instead, the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were governed by the draconian state-based organisations variously misnamed as Aboriginal ‘protection’ or ‘welfare’ boards.

These boards had complete control over the lives of the rightful inhabitants of the land, dictating births, marriages and employment. They were also responsible for Australia’s great sin, the Stolen Generations of children removed from their families.

Calling for a Voice, 100 years ago

The AAPA's radical proposals of Black representation and sovereignty saw them hounded out of existence, likely by the police. Credit: National Museum of Australia

Their primary focus was combating the poisonous impact of the NSW protection board, and advocating for Aboriginal people to have more say over the laws governing their lives.

In what would become headline news, the AAPA produced a manifesto calling for simple, but profound, changes for Indigenous people, including the right to land and a recognition of the sacredness of Aboriginal family life.

One of the points will sound very familiar in the context of today’s debate:

'The control of Aboriginal affairs… shall be vested in a board of management comprised of capable educated Aboriginals under a chairman to be appointed by the government.'

Activism, treaty and constitutional recognition

Vincent Lingiari was a warrior for his people, one of the great social figures of the 20th century. Source: AAP

But it wasn’t until 1983, almost 200 years after the arrival of the First Fleet, that a government body recommended making reference to First Nations people in the country’s founding document.

The Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs handed down its report calling for the government to consider a treaty with Indigenous people.

It also recommended a constitutional provision ‘which would confer a broad power on the Commonwealth to enter into a compact with representatives of the Aboriginal people’.

A failed referendum

The year after the referendum, thousands walked over Sydney Harbour Bridge for the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation event, Corroboree 2000. Source: Getty / John van Hasselt - Corbis / Contributor Getty

In 1999 the country held its most recent referendum. Although the primary purpose was to determine whether Australia would become a republic, there was also a separate question regarding the addition of a preamble to the constitution that would acknowledge First Nations peoples as the original inhabitants of the land.

As we know, that referendum failed, and constitutional recognition was relegated again.

New millennium, new momentum

Following the change in government, the Apology to the Stolen Generations began a decade of strong advocacy for constitutional recognition. Source: Supplied

- 2008 Following Kevin Rudd’s , the final report of the 'Australia 2020' summit recommended that strong rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people be inserted into the constitution proper, and not just as an introduction such as the preamble represented.

- 2010 - After becoming prime minister, Julia Gillard established the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition, co-chaired by Pat Dodson, tasked with guiding the government on the process of constitutional recognition.

- 2012 - The panel makes sweeping recommendations, including a constitutional ban on racism, and notes strong public support for Indigenous recognition.

- 2015 - The Referendum Council is established, and building on the work of the expert panel, they begin an extensive process of community consultation across the country.

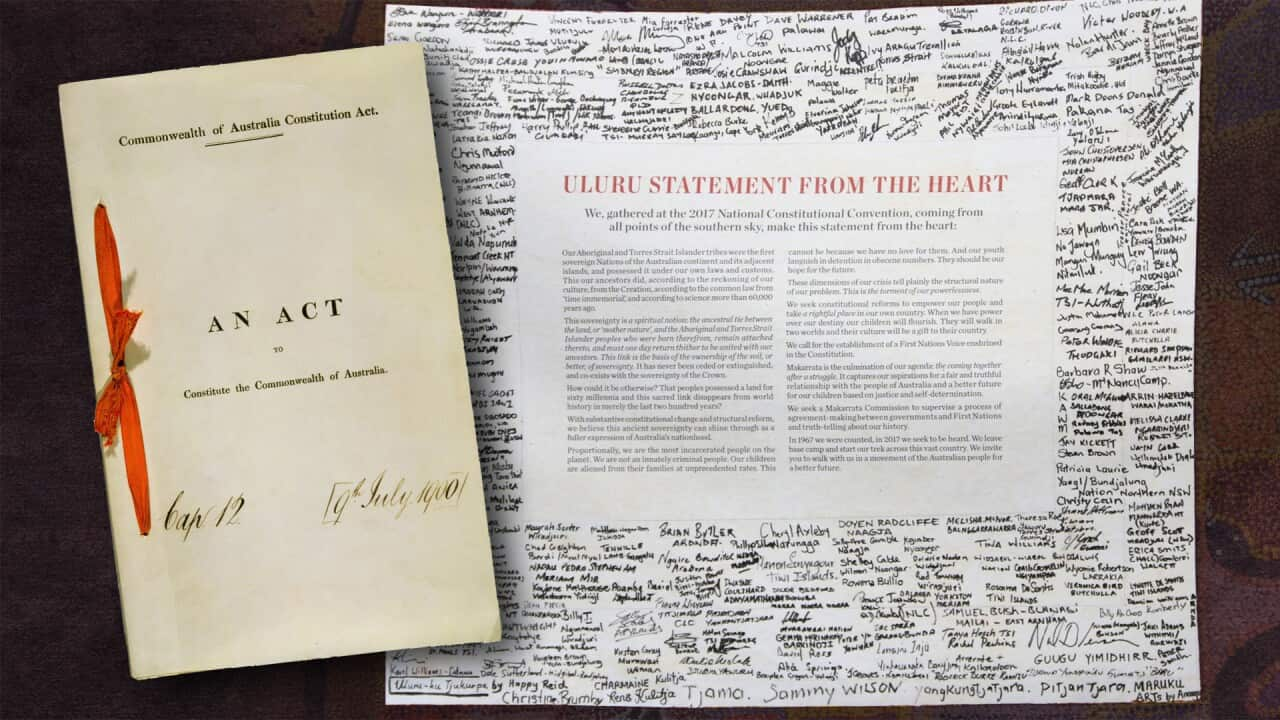

The Uluru Statement from the Heart

The opening ceremony for the National Indigenous Constitutional Convention held in 2017 that produced the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Source: AAP

Meetings were invitation only and capped at 100 attendees, comprising 60 per cent Traditional Owners, 20 per cent community organisations, and the remainder ‘key individuals’. It put “Aboriginal decision making… at the heart of the reform process”.

The dialogues culminated in the 2017 First Nations National Constitutional Convention.

250 delegates descended upon Uluru on Anangu Country. The assembled representatives nominated three areas where they believed the need was greatest: truth-telling, treaty, and a Voice.

Most of all, they declared that constitutional recognition must bring about tangible change in their communities.

So the, and with it the request to acknowledge First Nations people in the country’s blueprint. Following the Labor government's election last year, .

That question will now go to the public.