11 min read

This article is more than 8 years old

Explainer

What is a treaty and what could it mean for our people?

A look at what a treaty is and how it might change the political landscape for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Published

Updated

Image: Batman's treaty with the aborigines [sic] at Merri Creek, 6th June 1835. (State Library of Victoria)

Australia is the only Commonwealth nation that does not have a treaty with the land's First Nations peoples.

As the debate around constitutional recognition and a Voice to Parliament heats up, there are those who believe a treaty should take precedence.

But what exactly is a treaty, and what could it mean for community?

Treaty

John Batman claimed he signed a treaty with the Kulin Nation in 1835, but this 'treaty' was not valid, either by British law or the laws of Wurundjeri. Credit: State Library of Victoria

Treaties contain articles which outline the points of agreement between the parties.

A treaty is similar to a contract in that the parties to a treaty usually agree to take on certain responsibilities and duties which are legally binding.

Many European countries signed treaties with the Indigenous peoples of the lands they colonised.

However, when the British settled on Aboriginal land they declared it 'terra nullius' (land belonging to no one), and so did not see Aboriginal nations as sovereign powers to be negotiated with.

Sovereignty

The British relied on the fallacy of terra nullius to extinguish Indigenous sovereignty, but as the High Court found in the Mabo case, that sovereignty continues today. Source: Getty / Photo by Jeff Overs via Getty Images

Many Indigenous people believe that, as the British colonisers never entered into negotiations with Aboriginal people, sovereignty over their lands was never ceded.

First Nations have never ceded sovereignty. The land was taken by force and has been retained by force.Eddie Synot, Wamba Wamba

This argument also proposes that Indigenous people should regain that authority, and the power to govern our own lives.

In practical terms however, sovereignty may mean different things to different people, such as a recognition of the distinctive place of Indigenous culture.

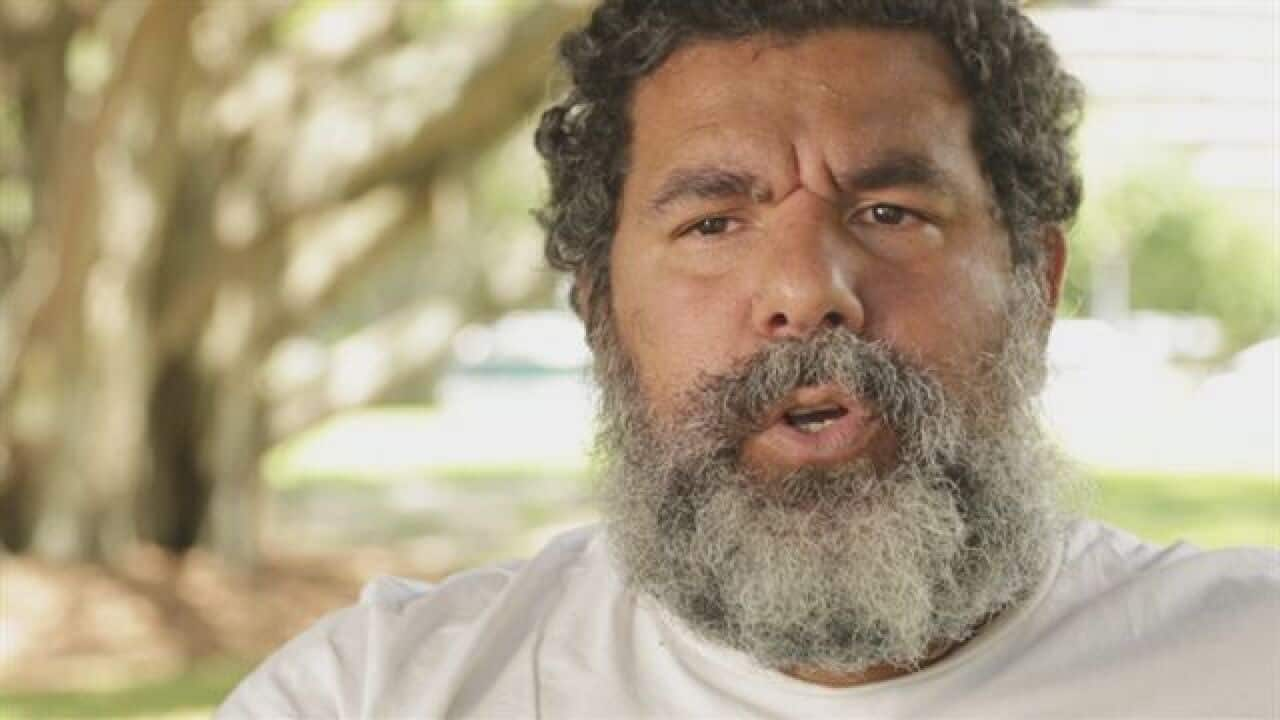

Jeremey Geia, now known as Murrumu Walubara Yidindji, has reasserted sovereignty over Yidinji land near Cairns.

Renouncing his Australian citizenship and reverting primarily to traditional law, Murrumu claims that his cultural lands were never given up and all additions to the land made by colonisers are attached to those lands and therefore Yidinji property.

Attempts at a National Treaty

Prime Minister Bob Hawke receives a diplomatic gift before the presentation of the Barunga Statement in 1988. Credit: Treaty Republic

While the Hawke government indicated their strong support for the concept of treaty and declared their intention to enact one by 1990, the policy was later abandoned in favour of 'reconciliation'.

Despite this history, treaty has repeatedly been put on the back burner, but the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart thrust it back into the national spotlight.

The Statement called for three things: Voice, treaty, and truth (in that order). The government has committed to following that procession, and all eyes are currently on the Voice; what a national treaty might look like is still unclear.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was the result of extensive consultation with First Nations communities across the continent.

a treaty could recognise the grievances of Aboriginal people, put in place measures to redress them, and establish "a path forward based upon mutual goals, rather than ones imposed upon Aboriginal people."

Indigenous academic Larissa Behrendt has also suggested that a treaty may include better protection for Indigenous rights, a basis for self-government and structures for decision making and further local treaties.

It is also unclear whether there would be a single national treaty between the government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people or whether a treaty would be signed with individual Indigenous groups.

Australia's first Indigenous silk, Tony McAvoy, spoke at the Redfern 'Need for Treaty' forum in March 2016. He argued that while treaty was achievable, the agreement must include an acknowledgement that Australia was not legally settled, and that the assertions of sovereignty made by the British colonies are fundamentally flawed.

The Victorian Treaty process

Yoorrook Chair, Professor Eleanor Bourke (centre) speaks to the media. The Yoorrook Justice Commission, the country's first official truth-telling forum, has been a central plank of Victoria's treaty process. Source: AAP / DIEGO FEDELE/AAPIMAGE

Most states and territories are in the process of developing some kind of treaty process with local First Nations, but one stands above the rest.

Victoria has by far the most advanced treaty process of any jurisdiction in Australia, developed over the last seven years between the Andrews Labor government and the state's various First Nations groups.

The stated aim of the Victorian treaty is to "negotiate the transfer of power and resources for First Peoples to control matters which impact their lives."

, and , which outlined the steps necessary to achieve treaty.

Over the next four years, a painstaking process of setting up the framework for negotiations took place.

An Aboriginal Representative body was established, self-titled as the 'First Peoples Assembly of Victoria'; an authority to act as umpire and a framework for negotiations were also set-up, in accordance with the legislation.

Following the creation of a self-determination fund in October last year, which provides financial backing so First Nations people can have 'equal standing' with the government during the negotitions, all the prerequisites had been achieved.

Negotiations will start at some point this year.

Another aspect of the treaty process in Victoria . It is the country's first official truth-telling forum.

Over the last two years it has seen heartbreaking and .

Treaty vs Voice

There has been ongoing debate about the appropriate vehicle to pursue ongoing relations between Indigenous Australians and the federal government.

As mentioned, the Uluru Statement called for Voice, treaty and truth, and the nation is in the process of enacting the first element of that proposal.

The amending of the Constitution to add a Voice seeks to give Indigenous people a greater say in government policies that affect them.

A treaty seeks negotiation and agreement between two independent parties, separate from their domestic legal systems, and truth refers to 'truth-telling', such as the Yoorrook Commission.

There have been some concerns that Constitutional recognition would negate declarations of Indigenous sovereignty by formally including First Nations people in the founding document of the Australian legal system.

However, numerous legal scholars including Professor , Anne Twomey and argue that this is not the case.

Tanya Hosch the co-Chair of Recognise, the campaign behind the movement to recognise Indigenous peoples in the Australian Constitution, has also : "For me and so many other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples who support treaty and constitutional recognition, we know that this is not an either/or choice."

What do other countries have?

New Zealand

New Zealand has , the Treaty of Waitangi, which was first signed by Maori chiefs and British representatives on the 6th of February 1840.

While the Treaty was originally signed at Waitangi on the North Island, copies of the Treaty were widely circulated and many chiefs from across New Zealand . This event is commemorated by New Zealand’s national day, Waitangi Day.

However, concerns have been raised over the exact wording of the Treaty as the English and Maori versions . There is also debate as to whether or not the Treaty allowed Britain to gain sovereignty over New Zealand.

We are still the only Commonwealth country not to have signed a treaty with Indigenous people. – Stan Grant

Canada

The Canadian Government, on behalf of the Crown, signed treaties with the First Nations peoples of Canada from 1701 onwards. These include the 11 signed with various groups of Aboriginal people as the British expanded into the central and northern regions of the country.

These agreements are by the Government of Canada and given protection under the 1982 Constitution Act s 35: ‘Aboriginal and treaty rights are hereby recognized and affirmed.’ Treaty Days are celebrated in many provinces and significant anniversaries are commemorated by an exchanging of gifts and discussions of treaty issues.

United States

The United States also signed many treaties with Native Americans tribes after the first 1778 Treaties were largely used by the United States to force Native Americans off their territory and in many cases the agreements made in the treaties were by the US.

Tribal sovereignty, however, is recognized in the US constitution and allows for the Native American peoples to engage with the Federal Government on a ‘ level.

Timeline of Treaty

1770 – Captain Cook arrives in Australia with to take possession of the land in the name of Great Britain with the consent of the Natives.

1778 – The United States signed their first written treaty, the , with the people of the Delaware, the Lenape people.

1835 - John Batman, a farmer in the Port Philip District of Victoria signed a with the local Indigenous people however it was disregarded by the Victorian Government.

1840 – The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in New Zealand between Maori chiefs and British representatives of the Crown.

1979 – The was formed with the aim to educate and persuade the broader Australian community of the prospect of a treaty.

1982 – The National Aboriginal Conference proposes a structure for each Aboriginal nation to negotiate its own treaty. are made to the Senate that a treaty making process follow the structure of agreements between the Commonwealth and the States, which are supported by the Fraser Government.

1987 – Prime Minister Bob Hawke that there should be “a clear statement and understanding by the total Australian community of the obligations that the community has to rectify so many of the injustices that have occurred during our 200 years.”

1988 – A statement of objectives for Aboriginal people is presented to PM Hawke at the Barunga Festival and he by calling for treaty negotiations to occur.

1991 – Political support for a treaty wanes and a policy of reconciliation is instead adopted and formalised by appointment of the . Yothu Yindi release their song ‘Treaty’ which quickly becomes an acclaimed protest song in the campaign for reform in Indigenous Affairs.

1998 – Prime Minister John Howard voices his opposition to a treaty and instead insists upon a non-binding recognition: “I hope we have some kind of written understanding. I don’t like the idea of a treaty because it implies that we are two nations. We are not, we are one nation.”

2000 – The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation recommends that the Commonwealth enact legislation to create an agreement or treaty which could act as an instrument to resolve reconciliation.

2010 – The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination recommends that Australia consider the ‘negotiation of a treaty agreement to build a constructive and sustained relationship with Indigenous peoples.’

2014 – Prime Minister Tony Abbott and the Chair of the Indigenous Advisory Council, Warren Mundine, both express their interest in the concept of treaty. They propose that rather than a national treaty that a structure be created for a treaty with the Federal Government and each Indigenous nation.

2016 – The Victorian Government commits to talks with Indigenous peoples on treaty and produces a set of treaty aims. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull reaffirms his support of Constitutional recognition as discussions of a treaty surface before the 2016 election.