4 min read

This article is more than 1 year old

Feature

In 1976, two Aboriginal men claimed England. Their actions mocked the lie of terra nullius

Wiradjuri man, Paul Coe and Bundjalung man Cecil Patten, rowed ashore and were the first to plant the Aboriginal flag in England, claiming it for their people.

Published 5 February 2024 10:54am

Updated 6 February 2024 6:53am

By Madison Howarth

Source: NITV

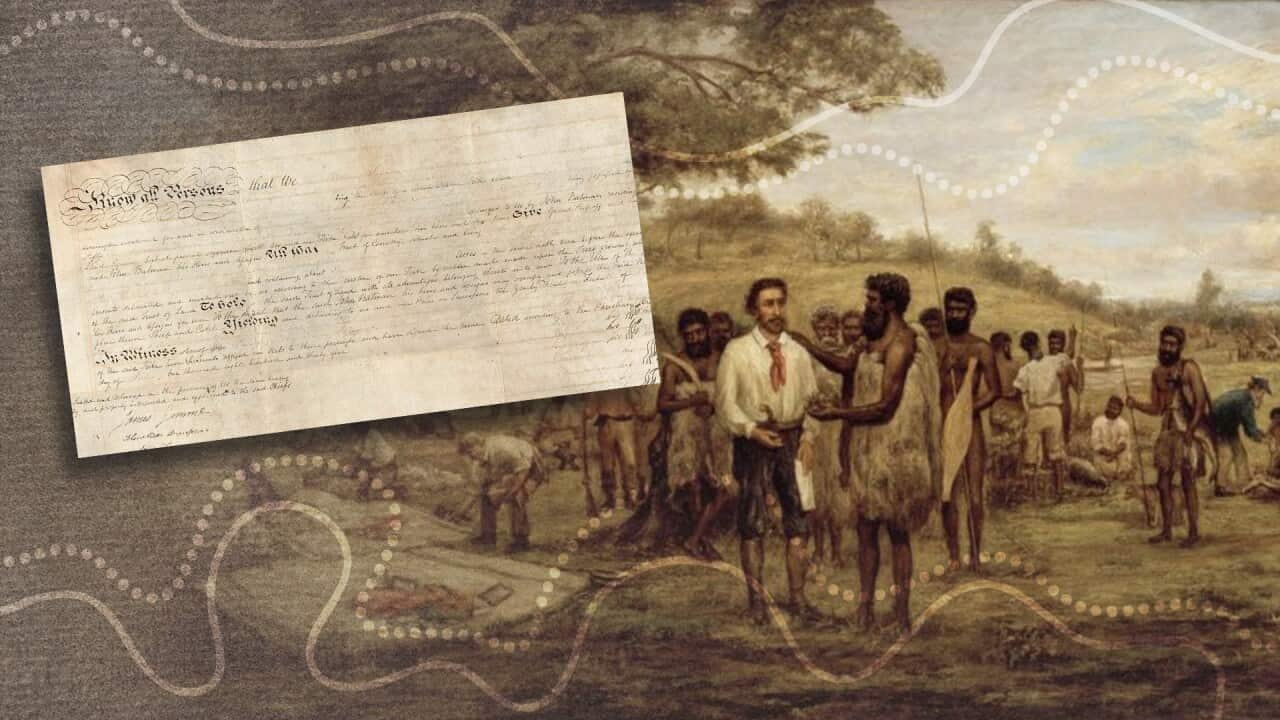

Image: Paul Coe and Cecil Patten were the first to plant the Aboriginal flag in England in a symbolic claim on behalf of Aboriginal people. (Supplied)

On the south-east coast of England lies the seaside town of Dover.

In November 1976, beneath the famous white cliffs and over ten thousand miles from home, Wiradjuri man Paul Coe and Bundjalung man Cecil Patten made history.

The two men planted the Aboriginal flag and symbolically claimed England for the first time.

Now, Coe’s daughter Jasmine, a Wiradjuri and British artist who is also Patten's niece, wants to shine a light on her family’s story.

“It was a symbolic claiming of England on behalf of Aboriginal people, and it was a reverse reminder of the events that happened 200 years before,” says Jasmine.

“They were the first two men to do this and it was a pioneering act of bravery, creativity, courage, humour and underlying truth.

"It was a way to provide this country [the UK] with another perspective of history because it is a shared history between the UK and Aboriginal Australia.”

Cold, capsized, crusading

A plaque in Dover, commissioned by Border Crossings and designed by Jasmine Coe, commemorates the event. Credit: Supplied

As the small row boat they had sank, the men had to swim the rest of the way in, enduring the bitterly cold waters, to climb up the pebble beach and plant the flag.

It was theatrical and it was a spectacle for bystanders.

“On the shore there was a group of people and they happened to be Australian tourists by complete coincidence,” says Jasmine.

The scene of two men coming to England and creating a performance piece may seem outlandish, but that was the impetus.

That ridiculousness … if you flip it, highlights just how ridiculous it is to claim ‘uninhabited land’ when people live there and it is inhabited and it has been for millennia.

Paul Coe himself laughs when reflecting on the moment.

"What we were doing on the beach in Dover, in the middle of English winter, I don't know," says Coe.

"It was so cold!"

From coast to courtroom

Coe says he and Cecil Patten wanted to use their own evidence against the Australian government in their land rights claims.

Coe would launch a case against the Commonwealth in 1979, asserting Aboriginal sovereignty.

Though it was unsuccessful, according to court documents, the case would leave open the "question of inherent rights to land" which led to the successful case of Mabo v the State of Queensland in 1992 which found; "Indigenous relationships to land and water could be recognised through native title."

Upon arrival to the UK, Coe and Patten wrote to the British prime minister outlining their intention and why they had 'claimed' England.

"What we were trying to get the British to do [was] to initiate proper process and not just rely upon what they did over 200 years ago when Cook arrived and planted the flag," says Coe.

"If the flag was good enough for Cook, it was good enough for us.

How can you take a country away from people and not expect those people to try and reassert their rights to their land and their Country?

This symbolic landing, unlike the landing of the First Fleet, was peaceful.

“They had beads and objects with them, it was a peaceful exchange,” says Jasmine.

“It was a peaceful gesture, but it was still proving a point.”

Last year, in partnership with Border Crossings festival, a celebration of Indigenous culture from around the world, Jasmine designed a permanent plaque to commemorate the event almost 50 years ago.

“It was an amazing moment because I felt, not only is it addressing a part of history that needs to be addressed here in the UK, but it was very special to be able to honour my dad for the lifetime of work that he’s done," says Jasmine.

“I hope that by having a plaque there it will contribute towards healing and it will create conversations around history.

“To be able to heal, people need to be listened to and heard and I think it’s a start.”