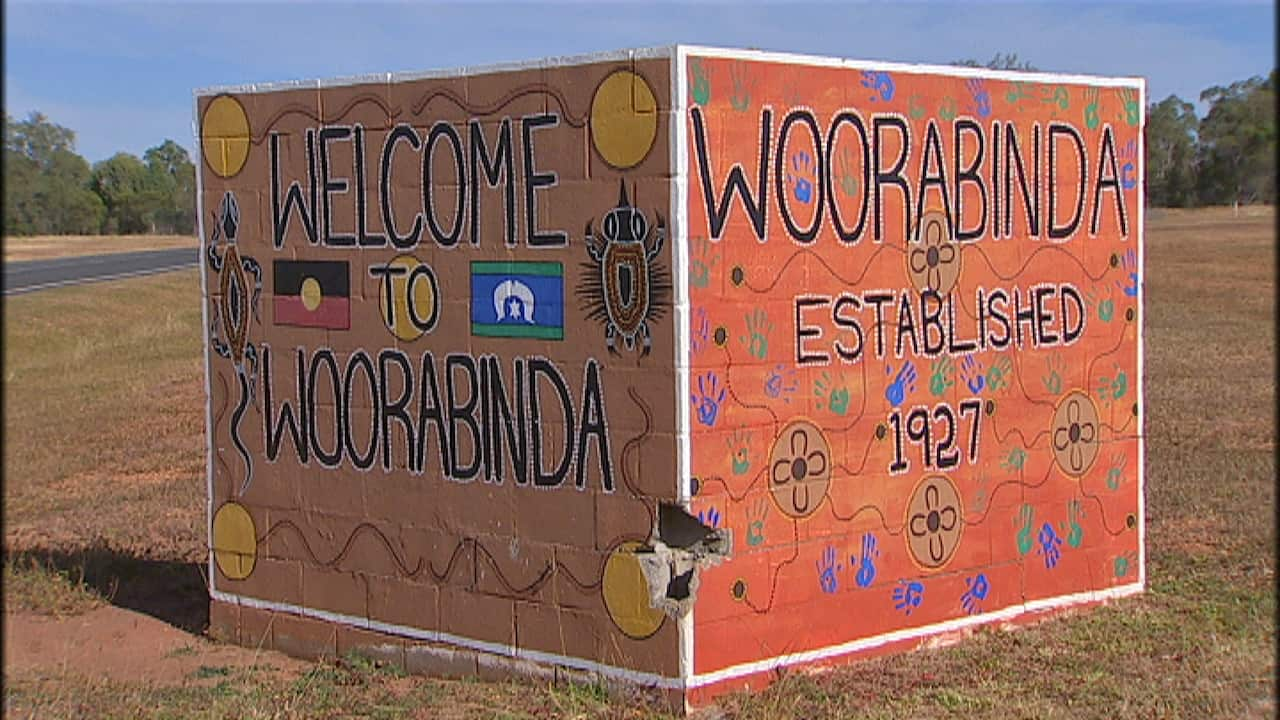

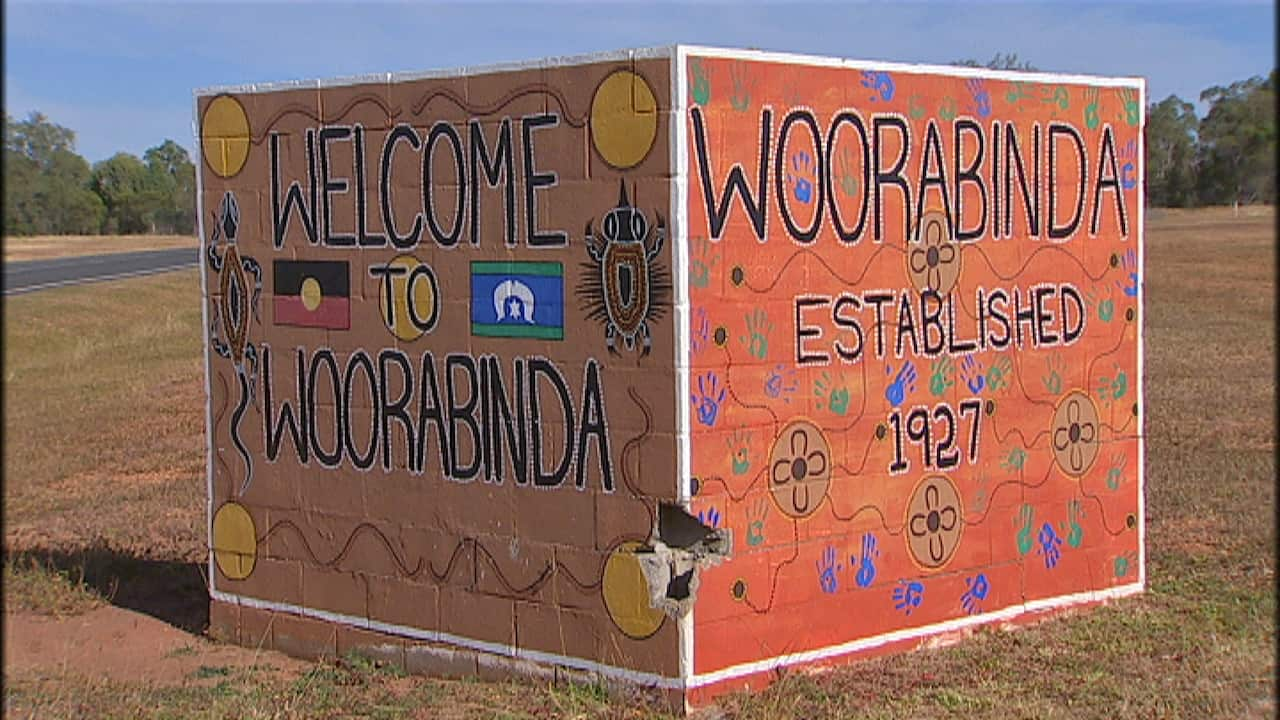

Aunty Diane Evans remembers how it all started 90 years ago.

“1926 they sent people up here to clear the land because it was full of prickly pears,” she said. “1927 they moved everyone from Taroom. Everyone come from their own bit of country and put them all on this place.”

It was a traumatic time, with people speaking more than 50 different languages moved from their homes around Queensland to the new settlement 170 kilometres southwest of Rockhampton.

People died on the trek to Woorabinda, including many among the 300 people made to walk over eight days, many barefoot, from Taroom. It’s an event that is now re-enacted for NAIDOC week.

“We need to look at how this community wants to deal with it, instead of just imposing something strong.”

It’s a beautiful place and Aunty Diane remembers the old days of rodeos, sporting events, dances, and going out bush with her family to find traditional tucker.

But popular local, Anthony “Big Uncle” Henry, who runs Boongara radio in town, says when he returned to his birthplace here 16 years ago he did not like what he saw.

“There were friends and family who were not getting on,” he says. “There was a lot of conflict. I saw an amount of petrol sniffing, a lot of dysfunction in families, and a community that didn't know how to deal with it.”

He said there were fights in the street being watched by large groups and “kids were walking to groups in 20-30 sniffing petrol”.

The community reached crisis point in July 2008 and the council banned alcohol, shut the pub and enforced restrictions to stop the flow of grog into town. Eight years on and the residents say complete prohibition is not the answer because it makes people feel like second class citizens.

“We need to look at how this community wants to deal with it, instead of just imposing something strong,” says Anthony Henry.

There was a time when the housing was just tin huts along the riverbank. But today, Woorabinda looks like any other small country town, with clean streets, new developments, and rows of stable housing

While there is progress in housing, areas like health still have a way to go.

“There’s a lot of health issues around depression,” says Anthony Henry.

“We are still getting a lot of men going to jail... there’s not a lot of people my age, in terms of men, around here."

And while healthy food options are available from the state government-run local supermarket, many come at premium prices, compared to cheaper fried food options next door. Newly elected mayor Shane Wilkie says while the situation is improving incrementally, more jobs are crucial.

Newly elected mayor Shane Wilkie says while the situation is improving incrementally, more jobs are crucial.

“I think it has come a long way but we still have a bit of a way to go,” he says. “I would still like to see about 75 per cent of our people being employed.”

He says more jobs would help people feel good about the town and “start to build up a pathway for our children who are attending boarding schools”.

He believes the town will get solar power, which will save money and provide some work.

Other initiatives include:

• The Australian Red Cross work in the community

• The Gumbi-Gunyah Women and Children’s shelter

• Woorabinda state school, which has school attendances officers

• A language program that teaches the children a mixture of traditional dialects.

Common among all these initiatives is a strong theme of re-establishing identity within the community.

“The kids knowing what tribe they come from and who their grandparents are, it’s about reconnecting to the old people,” says Diane Evans.

Mr Henry says there has been “enormous change” and there was more work to do.

“We are not where we would like to be. We would like our kids being capable of going around Australia and walking into jobs with the level of education they are currently receiving. We would like our community to be economically independent.

“I think we are on the right track. We know there’s going to be generations still stuck in what we had in the 80s, but the new generation is going to be there. We just have to build better structures to accommodate them when they want to move forward."

RELATED ARTICLE:

One community's fight to save near-extinct Aboriginal language