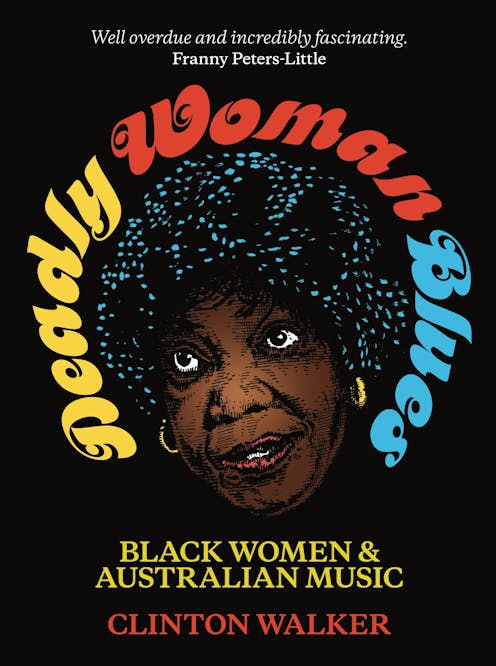

Seldom does a book about music attract the high controversy surrounding Clinton Walker’s Deadly Woman Blues: Black Women & Australian Music. On grounds of multiple inaccuracies and damaging reputational distortions, it was denounced by the very artists whose music it sought to celebrate as it reached bookstore shelves in February 2018. The publisher, NewSouth Publishing, within weeks on March 5. Deadly Woman Blues by Clinton Walker was pulled from circulation after various factual errors were revealed. NewSouth Publishing

Deadly Woman Blues by Clinton Walker was pulled from circulation after various factual errors were revealed. NewSouth Publishing

Yet Deadly Woman Blues should not be forgotten. It remains a useful and instructive example, albeit unintentionally, of the authorial burdens and responsibilities inherent in publishing other people’s stories.

With Deadly Woman Blues, Walker sought to produce a chronologically ordered biographical encyclopedia cataloguing the overlooked histories and achievements of black women in Australian music. This included not only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, but also expatriate women of the African diaspora and Indigenous communities of other countries. Promoted as the sister sequel to his critically acclaimed book of 2000, Buried Country: The Story of Aboriginal Country Music, which spawned a tie-in CD and DVD, this latest book sadly disappoints and offends in multiple ways.

Nardi Simpson, of the , first raised the alarm about Deadly Woman Blues on Facebook on February 14 after learning that it included commentary on her life and music without her prior knowledge or consent. She stated that she had been unable to secure a meeting with Walker to discuss this despite contacting him three times.

After eventually obtaining a copy of the book, she and her Stiff Gins colleague, Kaleena Briggs, wrote to NewSouth Publishing citing numerous inaccuracies in Walker’s telling of their story. The reply they received the day after the book’s launch at Gleebooks in Sydney on February 21 largely defended the approach taken in its production, yet stated that all of their suggested errata would be posted on the publisher’s website and that, as requested, the Stiff Gins entry would be removed from future editions.

Though a number of the affected artists were busy working at the Australian Performing Arts Market in Brisbane that week, jazz artist was present at the book’s Sydney launch, where she raised their many concerns about its distressing inaccuracies and distortions directly with the publisher.

With frustrated letters from Lou Bennett of , and Deborah Cheetham AO of , amplifying this refrain of discontent, NewSouth Publishing ultimately relented and announced it would withdraw the book from circulation. All errata provided by the affected artists are to be published on its website. As of March 6, as “Out of print”. for his book’s “errors of fact” that same day.

In many cases, those “errors of fact” were far from trivial. Rather, they were gross misrepresentations that trespassed into the private lives of the affected artists, inflicting serious distress and risks of ongoing reputational damage.

In Cheetham’s case, Walker made so basic an error as to mistake her place of birth. Cheetham was in fact born in the Nowra District Hospital, where her officious removal from her mother at three weeks of age is well known to have later inspired the plot of her acclaimed 2010 opera, Pecan Summer.

Speaking on ABC’s The Drum on March 6, Cheetham equably explained: “As a member of the Stolen Generations, to have the place of my birth stated with such careless inaccuracy was not only insulting to me, but to my mother and my grandmother’s experience.”

Her restraint was admirable given that Walker had egregiously insulted her several times in the book. She wrote to the publisher about this and shared this correspondence with us:

He could have used any image of me as a performer in the various gowns that I wear. However, he chose to show me in a suit and tie to illustrate his point that he believes me to be a cross-dresser. The fact that he omitted the post-nominal AO from my name in the chapter title, Deborah Cheetham Opera Snob, is disrespectful as well. As for the word “Snob”, I consider accessibility to opera as one of the key platforms of my work and that hardly defines me as a snob. Also, his treatment and paraphrasing of my feelings around my first meeting with my mother, Monica, is as rough as it possibly could be and very disrespectful to us both.

Walker’s book similarly demeans other women with such false accusations, but we have not received permission to cite their responses. His insults may be considered defamatory.

Missed opportunities

So, what went wrong with Deadly Woman Blues? Why was it not received as a triumph like Walker’s earlier book, Buried Country? How did it pass the rigours of peer review that an academic publishing house would normally impose, and how were its many obvious flaws permitted to go to press?

The answers to these questions are unclear, though clues can be found in the framing Walker himself presents in the book’s introduction.

On page eight, in an ill-conceived apparent attempt to absolve himself of any need to have interviewed or consulted with the artists about whom he writes, Walker states: “Deadly Woman Blues isn’t oral history like Buried Country, it’s graphic history. Not investigative but impressionistic. Based not on interviews but images.”

Emerging here as a matter of grave concern is Walker’s seeming belief that the oral histories of black women are unworthy of robust exploration, and that their achievements are better suited to his own impressionistic interpretations through imagery. For a book about music, this seems rather odd.

Accompanied on the same page by salacious, yet uncredited, vintage illustrations of semi-naked Aboriginal women, Walker reveals his nostalgic fascination with depicting his subjects through “a gallery of portraits, accompanied by the briefest of notes. Like an album of old-fashioned cigarette cards, or set of bubblegum cards. Like a variation on the now highly collectable Popswops cards that Scanlens put out in Australia in the mid-1970s.”

Based on portraits of each artist that Walker himself penned and partially exhibited at the Macquarie University Art Gallery in October 2015, his proclivity for titillating imagery re-emerges throughout the book’s pages. This is perhaps demonstrated no better than on page 162 in an image of an imagined cover for a fantasy CD by Christine Anu, in which a black line barely covers her bare nipples. In real life, Anu is depicted fully clothed on all of her album covers.

Having already denied his subjects any choice or agency in how or if they wanted their stories to be told, Walker’s bubblegum-card approach to history only serves to subordinate black women to the whimsical authority of his white male gaze, like a collection of chloroformed butterflies pinned to a curator’s specimen board.

Herein lies one of the most heartbreaking of this book’s missed opportunities. Had Walker only gone to the effort of consulting and interviewing the living artists he discusses, just as he did for Buried Country, then Deadly Woman Blues might too have been celebrated as an equally valuable triumph.

The other most heartbreaking of this book’s missed opportunities is that Walker has a genuine flair and passion for unearthing hidden histories. Part One and its accompanying discography, in particular, genuinely do introduce readers to many artists of yesteryear who are likely be unknown to all but vintage music buffs. Yet the veracity of this rare information is grossly undermined by the serious “errors of fact” concerning the numerous living artists who called for the book’s withdrawal.

Publishing standards

Ultimately, there is no way of knowing how Walker arrived at any of the information he presents in Deadly Woman Blues, as it is a book devoid of any citations, references or bibliography.

In an alarming lapse of both scholarly and journalistic standards of evidence, attribution and ethics, which any academic publishing house should have demanded, Walker’s literary sources remain a mystery, as do the original reference images upon which the many portraits he penned were probably based. Other books in NewSouth Publishing’s catalogue include this kind of apparatus. Perhaps the publishers felt that a book about music by black women would just be a bit of fun and therefore warranted lower standards.

, written by Mandy Sayer for NewSouth Publishing, and , written by Heather Morris for Echo, are recent examples of excellent books that demonstrate how authors can present deeply personal and sensitive material with great care and respect for the dignity and rights of the people whose stories they tell. This same dignity should have been extended to the living artists discussed by Walker in Deadly Woman Blues.

Walker’s assertion, starting on page nine, that there are few writers, Indigenous or otherwise, who specialise in Australian Indigenous music further reveals his limited knowledge of this critical field of research and NewSouth Publishing’s failure to adhere to rigorous peer-review processes.

In addition to DJ Hannah Donnelly, Clint Bracknell and Payi Linda Ford are Indigenous Australian scholars who write about Australian Indigenous music. Karl Neuenfeldt, Peter Dunbar-Hall and Katelyn Barney have certainly contributed to this discourse as well, but so too have numerous other music scholars including Allan Marett, Linda Barwick, Fiona Magowan, Elizabeth Mackinlay, Robin Ryan, Sally Treloyn, Myfany Turpin, Genevieve Campbell and Reuben Brown to name but a few.

Indeed, had Walker read Katelyn Barney’s edited book, , which emphasises the importance of equitable and co-operative approaches to music research between Indigenous Australians and others, then Deadly Woman Blues might still be in print today.

At best, Deadly Woman Blues is a lazy, under-researched effort that models how not to approach the task of publishing other people’s stories. Amateurish and unethical in its denial of their voices and agency, it has placed at risk the reputations, privacy and integrity of the very artists it sought to celebrate causing them preventable harm and distorting the public historical record. Both journalists and academics are bound by professional codes of conduct that prevent them from publishing material about people’s private lives without meeting rigorous standards of evidence, attribution and ethics, and there was a clear responsibility for both the author and publisher to have attended to this important matter before the book’s publication.

For these reasons alone, Deadly Woman Blues remains a useful resource that should not be pulped entirely. Rather, it should be kept in the rare collections of university and major public libraries as a reminder to us all that its many serious shortcomings should never again be repeated.

As to the question of who will now resume the challenge of appropriately producing the first comprehensive book about black women’s music in Australia, we have a novel suggestion.

NewSouth Publishing should fund an independent invitation-only conference for the living artists affected by Deadly Woman Blues. There, they could freely discuss if or how they want their legacies to be represented into the future. NewSouth Publishing should then fund any publishable output from this meeting that those women see fit to pursue with no strings attached.

We wish to thank numerous artists who have been affected by this book for their advice in writing this review.

Professor Marcia Langton AM is the Foundation Chair of at the University of Melbourne, and Professor Aaron Corn is Director of the at the University of Adelaide. Both Langton and Corn remain closely involved in the National Recording Project for Indigenous Music and Performance (NRPIPA), which they worked with many other colleagues and Indigenous community partners to establish in 2004.

Aaron Corn’s book, , is available from Sydney University Press.

Aaron Corn receives funding from the Australian Research Council. He volunteers as a Co-Director of the National Recording Project for Indigenous Performance in Australia.

Marcia Langton volunteers as a Steering Committee Member of the National Recording Project for Indigenous Performance in Australia.