- Full report on SBS on Monday, 15 September at 5pm

Jason* has been in an out of various West Australian prisons and detention centres for more than ten years. But unlike other prisoners, Jason has no set release date and he was never convicted of an offence.

Jason was deemed too brain damaged, reportedly from solvent abuse, to stand trial over a car crash that led to the death of his 12-year-old cousin in 2003.

Jason was 14 years old when his mother, Sarah*, dropped him and his young cousins off at a train station to head home to their aunties.

Instead they headed to a nearby shopping centre where they broke into a car and drove away with Jason behind the wheel. A high speed police chase ensued but was called off. Minutes later the car collided with another and Jason’s 12 year old cousin died at the scene.

Jason is now 25 years old. Sarah, who is suffering from kidney failure, would like her son to come home. She says the wider family is finally beginning to reconcile over the death.

Chief Justice voices concerns

Jason’s is not the only case of its kind. There are currently more than 30 people being held in indefinite detention in West Australia due to incapacity. About one third of them are indigenous.

Under the Criminal Law (Mentally Impaired Accused Act) 1996, a person may be placed under an indefinite custody order if it is found that they lacked capacity at the time of the offence or cannot understand court proceedings.

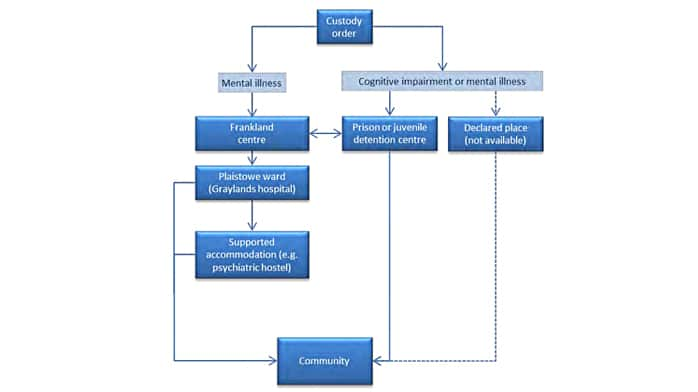

The Act applies to people with mental illness or cognitive impairment such as acquired brain injuries or foetal alcohol spectrum disorder. While those who are mentally ill can be placed in a specialised psychiatric ward, the only option for people with cognitive impairment is to go to prison.

From the April 2014 report 'Mentally impaired accused on ‘custody orders’: Not guilty, but incarcerated indefinitely'.

“There have been a number of cases in which there is no doubt that a person who has been declared unfit to stand trial under the act has spent much longer in prison that they would have spent had they been found guilty, he said. “That just seems, to me, to be wrong.”

“Locking them up indefinitely is a very expensive and very ineffective solution to that problem, we should be looking at a management solution that places them at a level of risk which the community can accept.

“Of course if they are very dangerous then prison may be best, but very few of the people we see in the courts are of that category.”

Custody orders are monitored by a government board with the final decision referred upwards to the Attorney-General, then the Governor.

Review pending

The state’s Attorney-General, Michael Mischin, says there are approximately seven people with cognitive impairments currently being held and only three of those are in prison.

“I'm conscious that they are not responsible but I’m also conscious that one of the paramount considerations is the safety of the community and also the safety of the person concerned,” Mr Mischin says.

A review of the act is underway but the Attorney-General says the earliest date for any legislative change would be early next year.

Not soon enough

Shadow Attorney-General John Quigley says it is too far away.

“We’ve been hearing about a review for years,” he says. “But people are languishing in prison unjustly at the moment.”

Earlier this year, Mr Quigley made a failed bid to amend the Act so that an order for detention could be no longer than a person’s sentence would be in even they were found guilty.

“Why should a person who has a mental disability be sent to prison indefinitely where a person who is fit to plead and is guilty be given a smaller term? It’s wrong.”

There are plans to provide options other than prison for the cognitively impaired. A special facility, called a Disability Justice Centre, is currently being built in the Perth suburb of Caversham, set to open mid next year.

There are plans to provide options other than prison for the cognitively impaired. A special facility, called a Disability Justice Centre, is currently being built in the Perth suburb of Caversham, set to open mid next year.

But after more than 10 years in detention Sarah is desperate for her son to be released into the community without conditions.

“The only thing we can hope for that the justice system will change so that it might give him a chance to get out and do something with his life,” Sarah says.

* Names have been changed for legal reasons