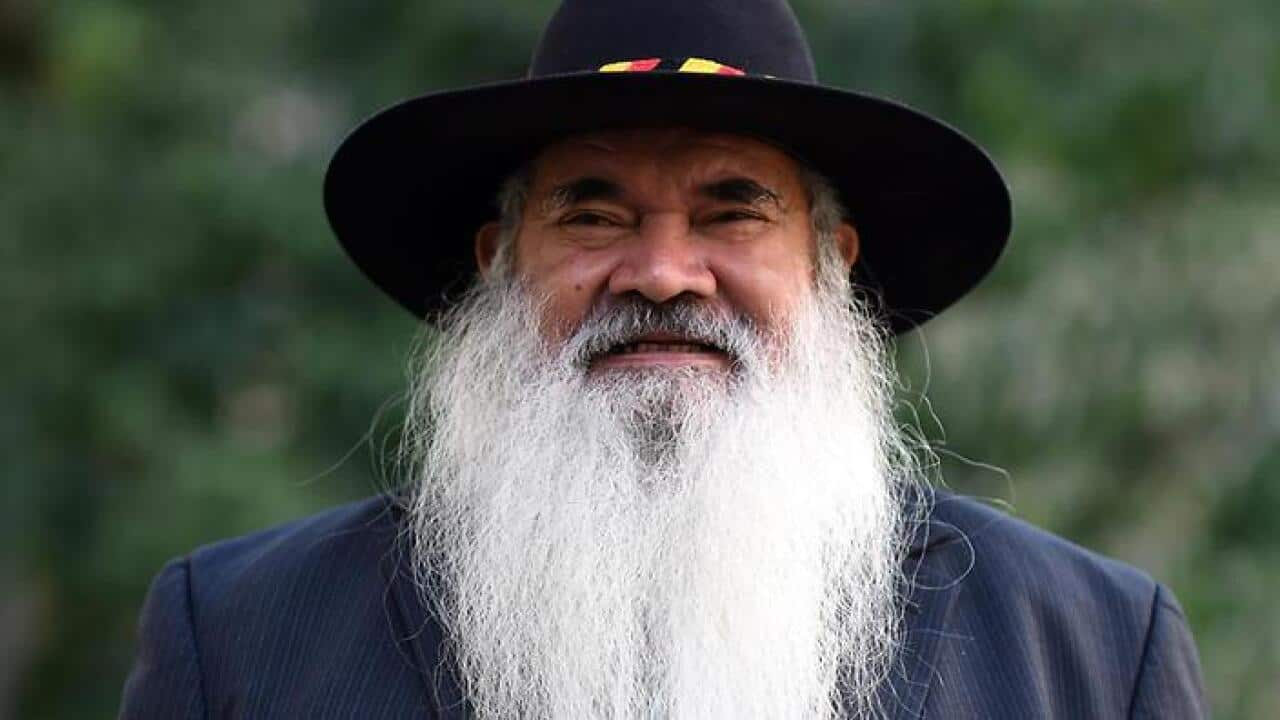

At 69 years of age, Pat Dodson is showing no signs of slowing down.

While most Australians are making retirement plans, Pat is in Parliament figuring out how he's going schedule in another meeting into his already jam-packed day.

As a Labor Senator for Western Australia, the work never slows, but Pat was ready for the challenge.

"Having spent much of my adult life trying to influence our national conversations, debate, government and the Parliament from the outside, it is now time for me to step up to the plate and have a go and try to influence those same conversations, debates, and public policies on the inside as a member of the Senate and representing Western Australia," he said.

Pat has spent his life dedicated to the cause.

He headed the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1989, and later the Council of Aboriginal Reconciliation, where he was given the title, 'Father of Reconciliation.'

But it's a name that Pat still struggles with.

"I get a bit embarrassed about that, not because of the hard work we put in, but I think there are many other people who would go before me," he told NITV News.

In fact, he lends most of his influence to leaders who have gone before him, and some who are still fighting.

"Everything was a struggle to achieve, but I think it was the goodness in many non-Aboriginal people that I saw, and the leadership I saw, like Sir Doug Nicholls, Jack Davis, Oodgeroo. There were a range of serious leaders we had, Faith Bandler, of course, Gary Foley, Bruce McGuinness, Vincent Lingiari. There was a range of leaders across the nation who were standing up saying that we needed better things done and they all helped to shape my views," he says.

While his humility is evident, Pat has definitely earned his way to the top.

After his retirement from the Reconciliation Council, Pat founded the Lingiari Foundation and created the Kimberley Men's Health Project while lending his time to higher education.

He was later awarded the International Peace Prize in 2008, for 'for his courageous advocacy of the human rights of Indigenous people' and 'for a lifetime of commitment to peace with justice'. But Pat's crusade to make life better for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples began long before.

But Pat's crusade to make life better for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples began long before.

Pat at the 50th anniversary of the Wave Hill Walk-Off Source: Supplied

He was born in Broome in 1948, a time when Indigenous Australians had little to no rights. He remembers some believed then that the Aboriginal race would eventually die out.

"It was very much the thinking that underpinned the Constitutional framing, but to be confronted by that in early life was a bit of mystery. How are you gonna disappear, was something gonna happen to us?" he wondered.

His family were forced to move to Katherine in the Northern Territory after Western Australian laws didn't allow his Aboriginal mother and Irish-Australian father to be together.

But sadly, not long after, Pat was orphaned at just thirteen. He and his younger brother Mick were forced to become wards of the state.

Pat remembers the injustices Aboriginal people faced when he was a young man working on a cattle station in Katherine.

"Old people used to walk back to their little humpies in the bush carrying water with yolks after working all day in someone's house, ironing and cleaning the house, and chipping the grass with a little tomahawk, there were no lawnmowers in those days," he reminisces.

"So the way in which Aboriginal people were treated was really embedded in me, it drove me to want to become better educated so I could be of use and at least have some understanding and have a capacity to argue about things that are not right in our society. I suppose that started me on the road to many of the things I've done, certainly, ultimately ending up here as a senator."

Today, Pat is part of the historic Indigenous caucus of the Parliament serving in his hometown of Broome. It's here, and other regional and remote communities, that his passion to fight for his people is ever-present.

"People would have no idea in the main about how they live, what happens to them, what services they get, they wouldn't know that they've got no Bunnings out there, got no Woolworths, got no IGA, they got no idea what the social, political, economic positions are of those communities," he says.

As a senator, Pat hears of the many injustices still faced by First Australians.

He says his work inside the Parliament is even tougher than the outside. "It's so hard because everyone's preoccupied with energy problems, same-sex marriage problems, jobs and growth mantras whether people are getting jobs or not, education policies, universities, which are all legitimate things, but because they affect the majority of people, the minority group like us as Indigenous peoples, we tend to be an afterthought," he says.

"It's so hard because everyone's preoccupied with energy problems, same-sex marriage problems, jobs and growth mantras whether people are getting jobs or not, education policies, universities, which are all legitimate things, but because they affect the majority of people, the minority group like us as Indigenous peoples, we tend to be an afterthought," he says.

Source: AAP

From marching in the streets to serving as a senator, Pat says he's still frustrated with the whole system.

"You get frustrated with the machinery things, you get caught because you know the passion, you know the concern, you know the aspirations of many of our people behind all of that," he says.

But after a lifetime of tireless protest, Pat is even more energised to continue the fight not simply as an activist but as someone who has the power to change and create policy.

"The richness that I see in Indigenous people's culture and society, and as individuals and as collectives, that I see as valuable. When I see it put down, or disregarded, or belittled that just fires me up to try and do something about it. A lot of people do this out of prejudice, out of racism, out of ignorance but they miss the richness of who we Indigenous peoples are and the contribution we've made but also the further contribution we'll make in this nation as we go forward."