In Australia, kids are settling into another year at school. Homework, lost sunhats, and NAPLAN tests are the biggest issues parents worry about.

In the refugee camps of Europe, the situation is a lot different. In 2016, 173,450 people, fleeing mostly from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, arrived in Greece by sea, a treacherous journey that claimed thousands of lives.

Today, 62,000 refugees remain in Greece. They live in camps like Skaramagas, an old shipping dock located 11 kilometres west of Athens near the port town Piraeus, home to 3,200 people. “Looming in the background are huge cranes, and shipping containers still line part of the camp's border,” says Anita Dullard, Emergency Communications Delegate with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. “The entire site is concreted, no grass or trees. Still, it's among the better camps in Greece. People have been living in containers with electricity and small bathrooms, rather than tents.” At Skaramagas, Red Cross provides basic health care, including general practitioners, midwives, paediatricians and dentists, but access to education remains a problem for refugees and migrants, some of whom have never been to school.

At Skaramagas, Red Cross provides basic health care, including general practitioners, midwives, paediatricians and dentists, but access to education remains a problem for refugees and migrants, some of whom have never been to school.

Aid organisations co-facilitate activities with people living in the camp to provide learning, skills development, community and pyschosocial support. Source: Credit: Anita Dullard/IFRC

In July 2016, the Greek government announced a plan to send 22,000 refugee children to school, before classes started in September.

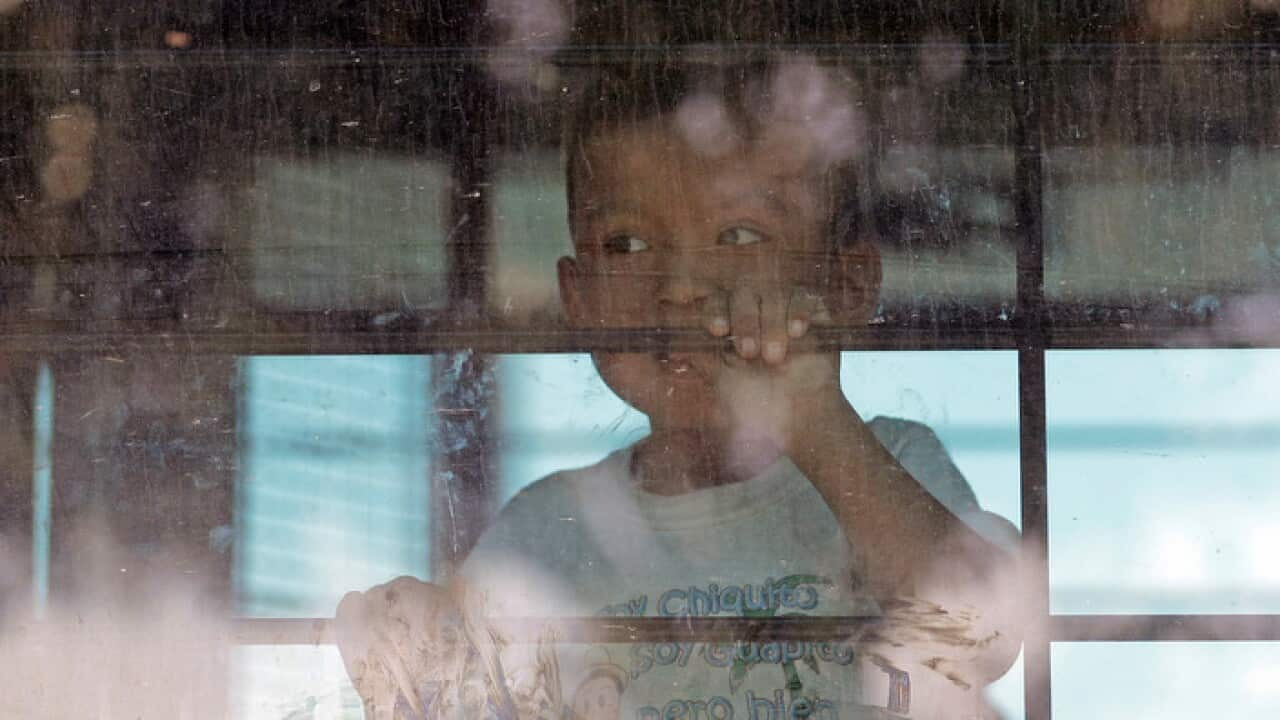

Every afternoon from, 2pm to 6pm, refugee children living at Skaramagas catch the bus to the local school where they study English and maths as well as Greek, to prepare them to integrate into the main school program. “All children must be vaccinated and have a medical examination in order to register for school,” says Dullard. “Red Cross provides these services to children across Greece.”

We feel bad because it’s three years since the children had any formal schooling.

In February 2016, Eman, an Arabic teacher from Syria, fled her home in Idlib – a city in north-western Syria – with her husband and their three children, Wajd, 18, Zakaria, 17 and Mohamad, 14. The family has lived at Skaramagas for the last eight months.

In Syria, Eman’s children attended school when they could. “Constantly, there were planes overhead and bombs,” she says. “We were always afraid to send our children to school.”

Now in Skaramagas, Mohamad is the only one who regularly attends school – an Arabic school located in the camp, one of numerous makeshift classrooms that have sprung up on site. The other two, Eman says, don’t go to school. Wajd, who left Syria midway through her final year of high school, learns English with the Red Cross where she also volunteers as a translator. Like many migrant children, Zakaria refuses to attend classes. “The children don’t want to go to school to learn Greek or a language they may not use,” Eman says.

Eman and her family hope to settle in another European country like Germany and are currently waiting to hear if their application to relocate has been successful. “I feel always upset, and worry about whether I have made the right decision. Living here I wonder if it would have been better to have stayed in my city and died. This isn’t our life,” she says. “When we left Syria I was looking for a better future for my children. Always it was for my children. Now everything is lost.” Her daughter Wajd is more positive. To keep busy in the camp, she is learning Greek and how to play the guitar. She hopes to one day continue her education. “I was interested in chemistry,” she says. “My dream is to be a chemist.”

Her daughter Wajd is more positive. To keep busy in the camp, she is learning Greek and how to play the guitar. She hopes to one day continue her education. “I was interested in chemistry,” she says. “My dream is to be a chemist.”

Eman and her daughter Wajd fled Syria with Wajd's younger brothers Zakaria and Mohamad. Wajd hopes to finish school one day and become a chemist. Source: Anita Dullard/IFRC

Local Taliban shut down the schools in the west Afghanistan region where Abdullahad, another resident of Skaramagas, lived with his wife Fatema, 18-year-old daughter Aisheh, and 15-year-old son Freidon. “My children haven’t ever been able to regularly attend school,” he says. “We had to leave for our children to have a future.”

The family endured a hellish 48-day journey before arriving in Greece. “We had to walk for days, and through the mountains between Iran and Turkey,” says Abdullahad. “We saw dead bodies of people who had tried to pass.”

Both Abdullahad’s children learn English with the Red Cross. Freidon is enrolled at the local school but Aisheh, who also teaches Persian at Skaramagas, is too old to attend, “even though she has never had the chance”, laments her father.

Image

Despite efforts by authorities to enrol refugee kids in school, often settlement offers the best opportunity for education. Khalif, a Kurdish Iraqi, left Iraq three years ago with his wife and six children. They spent two years in Turkey before arriving in Greece. “We feel bad because it’s three years since the children had any formal schooling,” he says.

The children were set to start at a nearby school the following week when they received the news that they were leaving Greece. “A week ago my brother told the German Red Cross that we were here and now they’re helping us to go to the same city as my brother,” says Khalif.

Their son Nessuan, who has been learning English with the Red Cross for two months, says he can’t wait to go back to school. “I think I want to be a doctor,” he says.

airs over three consecutive nights, October 2 – 4, 8.30pm, LIVE on SBS Australia and streaming live at SBS On Demand.

Join the conversation #GoBackLive