A sea of coastal bush sped past the train windows, a blur of missed homelands. It was 1931 and the train echoed with the cries of children. That train wasn’t out of control though, not running off the tracks, not falling from a cliffside.

That train held stolen children.

One of them was my Nanna, Dorothy Carter. Dot as she was called, even by my dad, was 10 years old when she was put on the train to Sydney. Desperately clutching to her twin sister Dulcie; two messes of black curly hair, one light skin and one darker, intertwined and gasping between howls on the long journey.

Every time I leave my daughter, my shoulders tighten and my stomach spins. That fear, that one day someone will take my baby can be overwhelming and all-consuming.

No matter how hard Nanna tried to scrape together money once she was grown, she never got to see her mother again. She lost her mother, country, culture, and connection. Nanna passed that trauma down, to her children and to me. I watch through the train window as it twists round the Hawkesbury River and find myself crying. Every time I leave my daughter, my shoulders tighten and my stomach spins. That fear, that one day someone will take my baby can be overwhelming and all-consuming.

My Nanna Dot was born on Bundjalung country, one of 12 children. Nanna grew up around Casino, Mallanganee and Jiggi. Up before the first magpie’s song, Dot and her siblings went with their mum to work. Of all the jobs their mum had, Dot’s favourite by far was watermelon picking. Reading through her letters now, I feel the loss of her childhood deep in my gut. “During the day two or three melons used to get broke. So mum and us kids would find a shady spot and have a feed of melon.”

“During the day two or three melons used to get broke. So mum and us kids would find a shady spot and have a feed of melon.”

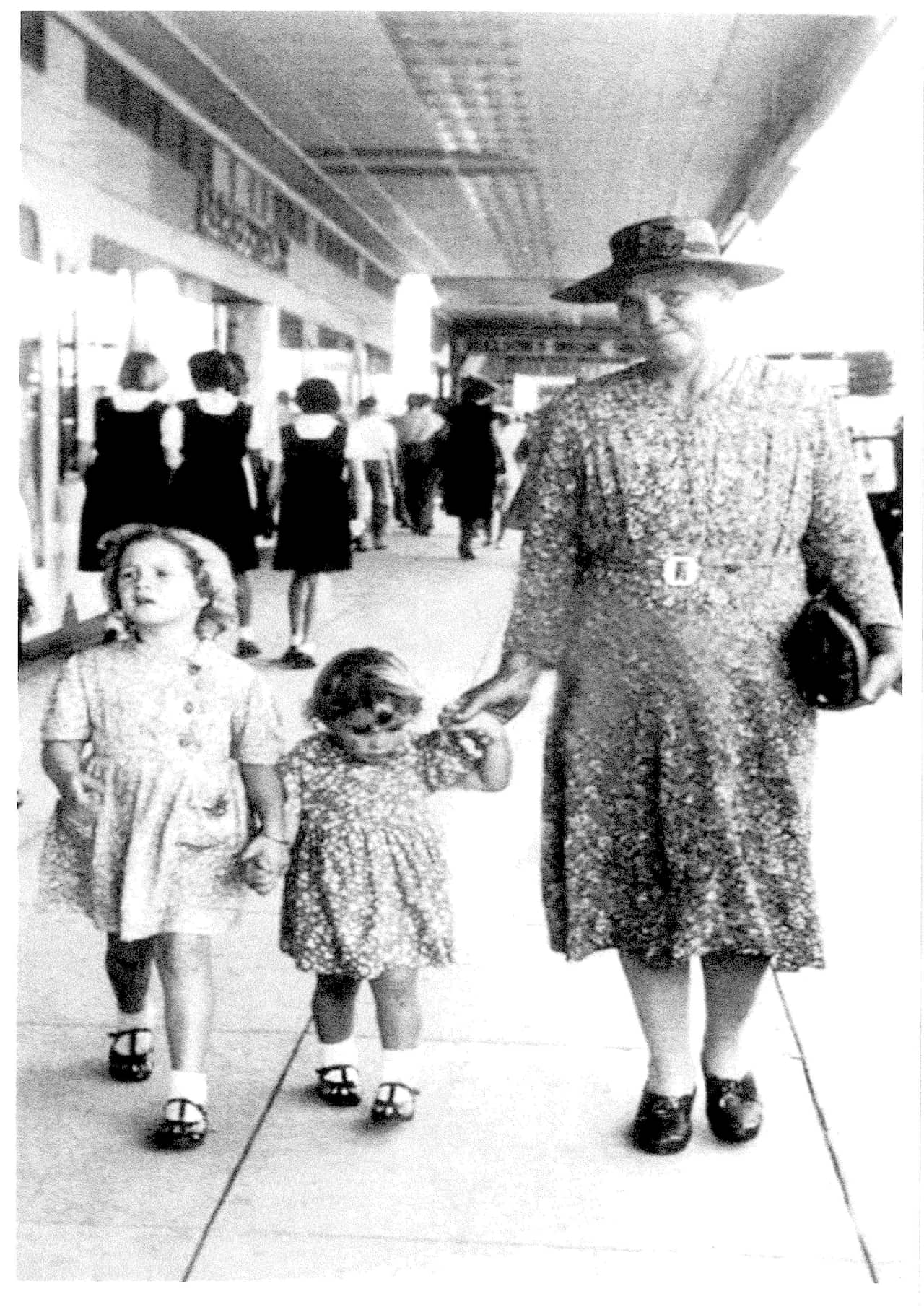

Dot's mum, Jane Maria Carter, the author's great gradmother with her other grandchildren Peggy Pheeney and Shirley Dudgeon in the 1940's. Source: Supplied

Dot’s mother, Janie Maria Carter, a Bundjalung woman with a white father, was an itinerant worker. She would take any job that allowed her to bring her youngest children along. The problem, as the government saw it, was that Janie was a blakfulla. An unmarried blakfulla raising 12 mixed children. Some of them were light-skinned. That light skin hid my Nanna’s truth for the next 63 years.

The welfare took one of Dot’s younger brothers, four of the youngest girls, and an eldest sister who was unmarried and pregnant. I was only seven when Nanna told her truth, too young to see the gravity of her trauma. Now as a woman, understanding how desperately my child needs me, I can barely get through this part of her letter. “We went to court in Lismore one day, only the eldest two girls were allowed inside. Then two or three days later we went to the courthouse again to meet the welfare woman who took us on that train.”

“We went to court in Lismore one day, only the eldest two girls were allowed inside. Then two or three days later we went to the courthouse again to meet the welfare woman who took us on that train.”

Nanna Dorothy. Source: Supplied

Together Enid, Grace, Dorothy, Dulcie, Lily and Freddie were sent to . A place known for internal examinations and strip searches. They endured two weeks of hell masqueraded as purgatory, then they were ‘fostered out’. The kids were taken in by a Men’s Boarding House owner called Mary Dummett, a white woman who insisted on being called Aunty Mary.

“She was very strict with us, and cruel.”

Now in Balmain, far from the sacred Clarence River, Dot was a ‘house maid’ at just 10 years old. Her days were filled with keeping house, rearing her youngest brother, and if she was lucky, a bit of schooling. She did all this, believing as her mother had told her, if she was good, she could come home again.

Until 1965, my Nanna believed that she just wasn’t good enough to go home. Trying her best to be a good kid was never enough. It was in ’65 when she was 44 that she could finally go home and visit family, although her mother had died in ‘56. During this trip to see her sister Enid, she explained what the judge had said. “We were exposed to moral danger, they took us cause we’re Aboriginal.”

“We were exposed to moral danger, they took us cause we’re Aboriginal.”

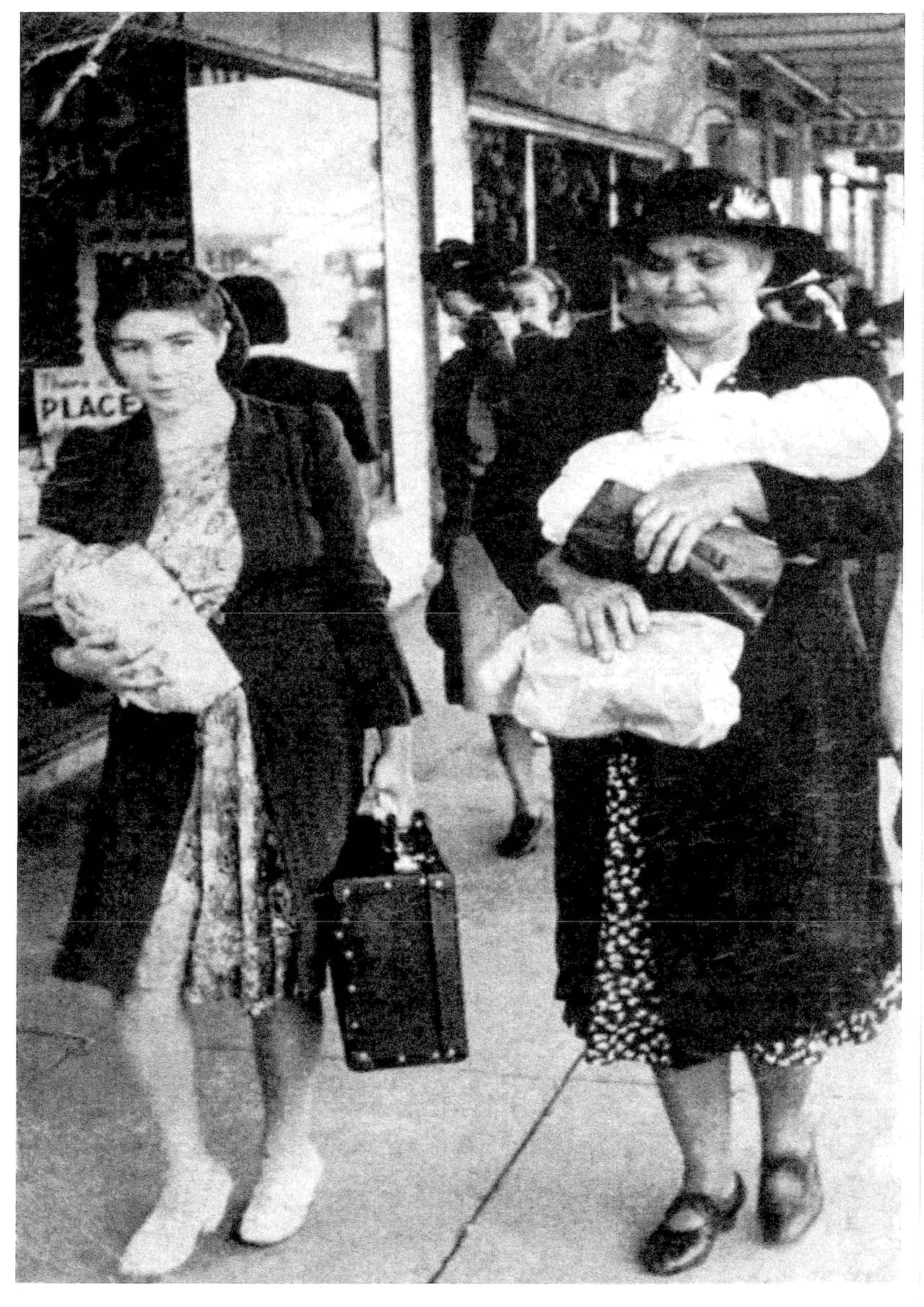

Dot's mum, Janie with her other daughter Ellen Agnes Louisa Dudgeon in the early 1950's. Source: Supplied

All her siblings knew we were Aboriginal, it was not a secret, how could she not have? How could this lie have lasted so long, that even she believed it herself? Even after having a dark-skinned first born, that seemed to surprise everyone. I guess trauma does that to a person. And now I carry that for her, passed down in my blood memory. It shows up in fear, in anger and in my desperation to understand who the hell I am.

My nanna died in 1996 when I was only nine. I never got the chance to ask her about our people; never had a moment to work through her shame and show her how amazing it is to be Koori. Now us younger generations are tasked with the feat of reconnection as we navigate and fight through dead ends, and long held secrets. I spend my days fluctuating between imposter syndrome and being staunch in my Aboriginal identity.

My nanna died in 1996 when I was only nine. I never got the chance to ask her about our people; never had a moment to work through her shame and show her how amazing it is to be Koori.

My dad is scared to even try to reconnect with our community. He is proud but careful in his identity, more concerned about overstepping his welcome as a mixed heritage man. It feels like I am constantly fighting, running up hill against archived government files and historical societies. This is why truth telling is so important in my family, this loss of connection cannot happen again.

My cousins and I, we refuse to let colonisation win. So we take our time, support our children in culture, we give back to community, share our stories, our Nanna’s story, and we work towards the truth that was stolen on a train to Sydney in 1931.

Week runs 7 - 14 July 2019. For information head to the official . Join the conversation #NAIDOC2019 & #VoiceTreatyTruth