UNDER HIS EYE

'He would know where I was before I got there'

Rocelle’s* blood ran cold. At the door was Robert*, the man she had tried to get away from.

She forced herself to stay calm and pretended she was willing to get back with him in order to placate him.

She had learned the hard way it was better to create a charade of getting along with him to buy time before the inevitable explosion of rage and physical violence that marked the 10 years of their relationship.

Rocelle had tried to leave Robert more than a dozen times to local refuges. Every time she left, he traced her and cajoled her to come back.

She thought she had finally succeeded this time, leaving with just the clothes on her back, after renting a home she had found on the website Gumtree. The house was a non-descript shopfront façade in a commercial area in Melbourne.

"He would know the exact time I would finish work and how long it took me to get home."

Following advice from police, Rocelle had also changed her routine, mixing up her shifts at the medical surgery where she worked with nights and weekend work.

But then Robert showed up at the house, saying he was in the neighbourhood and had noticed her car and decided to “drop by”.

It wasn’t long before Robert started turning up at night at the medical surgery where Rocelle worked. Then he would turn up at her doctor and psychologist appointments. That was when she realised that Robert’s methods were not random but more sophisticated.

“He had tracking devices. He would know where I was before I even got there,” she says.

Tracking software, or ‘spyware’ can be bought online and allows a perpetrator to remotely track a person’s location, read messages, trace keystrokes, listen in on phone conversations and even access a person’s camera, all remotely and without detection.

While some spyware software like Mspy, Teensafe, and Flexispy are marketed as child-safety surveillance programs, there is no way to monitor how they are used, accessed and bought online by perpetrators A recent report by Deakin University found that the consumer spyware industry is increasingly marketing products as a way to ‘catch cheating spouses’.

A snapshot of spyware ‘TeenSafe’. Spyware can be downloaded on a phone through ‘jailbreaking’ the device – bypassing the phone’s safety features to allow the phone to install spyware. Source: WESNET

A snapshot of spyware ‘TeenSafe’. Spyware can be downloaded on a phone through ‘jailbreaking’ the device – bypassing the phone’s safety features to allow the phone to install spyware. Source: WESNET

Rocelle says the surveillance started early in the relationship.

“He would call me when I finished work. He would tell what I needed to buy or what he needed. If I came home late, he would ask, ‘Are you seeing somebody? Why did it take you so long?’.

“He would know the exact time I would finish work and how long it took me to get home. If I was a minute late, forget about it. I was terrified of returning home.”

The couple met in August 2004, a few months after Rocelle’s father died and when she was feeling isolated and stricken with grief.

Robert moved in quickly, assuming control of Rocelle’s bank accounts and ATM card. He became brutally and unpredictably violent.

“He would spit in my face, slap me, punch holes in the wall. The amount of holes we had! I would suffer the rest of the night in silence. I wasn’t allowed to talk,” she says.

Rocelle said the abuse escalated after she left the 10-year relationship, and included Robert leaving threatening direct messages on Facebook under a fake profile. She would also receive anonymous calls from non-registered SIM cards.

“He made my life a living hell once I got out. I thought after leaving I would be safe, but I went from one battle to another. To him, I was his property.”

Much of the abuse was untraceable, but the emotional terror of her partner’s surveillance and tracking still lives with her.

“My anxiety was so severe I couldn’t eat or sleep and I had night tremors and PTSD in overdrive. The panic attacks were so fierce that I couldn’t even get the mail. I was that frightened,” she says.

“At the shops once, I had such a severe panic attack I forgot who I was. I forgot my own name.”

TRACK AND CONTROL

The methods used to track and harass have expanded in the digital media era.

“Gone are the days where you could put 200km between you and your perpetrator because the technology follows,” says Karen Bentley, a tech abuse expert for The Women’s Services Network WESNET.

Karen Bentley. Source: Supplied

Karen Bentley. Source: Supplied

Bentley, also the National Director for the Safety Net Australia Project, a group she founded for WESNET to examine the impact of tech-related domestic violence, says the use of spyware and other forms of technology-facilitated domestic violence are not unlike cyber tracking used by authoritarian regimes and intelligence services.

However domestic abuse perpetrators had an easy shortcut to surveillance, often already having easy access to information they need - from shared passwords, answers to secret questions used to reset passwords, and family laptop and phone accounts.

Even access to an un-logged out Gmail browser could be used as a centre point to change passwords for access to social media, banking and government sites.

“The thing around domestic abuse [and] family violence is that it’s actually much more targeted. Instead of being at risk from a stranger in the cybersphere you’re now being targeted by someone [you know].”

THE WEB OF CONTROL

For Liz*, 49, the online surveillance started when she decided to leave her partner Tim* after eight years together.

The couple split in 2010. During their divorce, Tim accessed intimate pictures and messages on her computer which she had posted to a dating site during their separation. He sent the messages to Liz’s family and friends, and supplied them in court documents to assert she was an unfit mother.

The act shrunk Liz’s social circle and left her socially crippled, isolated and terrified of interacting with her community.

It was, however, Tim’s continued involvement in her life, beyond his allocated time with their son, that created a spectre of fear. When their young son Michael* would use his digital games and electronic devices before bed, it was Tim who was able to tell her what time her son was going to bed, in her own home.

“He’d say to me ‘I don’t think he is going to bed at the right time’.” Liz had no idea how her ex-husband, who shares custody, was tracking the movements of their son when he was in her home. She suspects Tim was using spyware.

Once when Michael came home sick from school, Tim was first to call up and contact him.

“It was chilling,” said Liz. “It’s hell. It’s terrifying for your child to come home sick and within 15 minutes of leaving school for your ex-partner to know that and be calling him.”

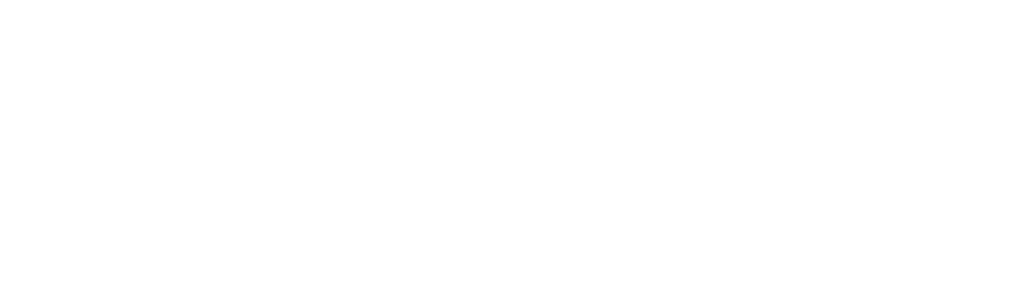

Your phone can track your location using apps such as Google maps, Uber, Trip Advisor, social media sites, location-based games and online commercial apps. Disabling location tracking requires manually disabling the feature in settings or changing settings to trace location only ‘while using app’. Source: WESNET

Your phone can track your location using apps such as Google maps, Uber, Trip Advisor, social media sites, location-based games and online commercial apps. Disabling location tracking requires manually disabling the feature in settings or changing settings to trace location only ‘while using app’. Source: WESNET

On the Apple family sharing account, everyone in the family is able to see where every device registered on the account is located. It also shows when the device was last active, allowing a potential abuser to pinpoint where every person in the family is at all times using precise satellite tracking imagery.

On the Apple family sharing account, the admin is able to see where a phone, registered in the family, is located using precise satellite tracking imagery. Source: WESNET

On the Apple family sharing account, the admin is able to see where a phone, registered in the family, is located using precise satellite tracking imagery. Source: WESNET

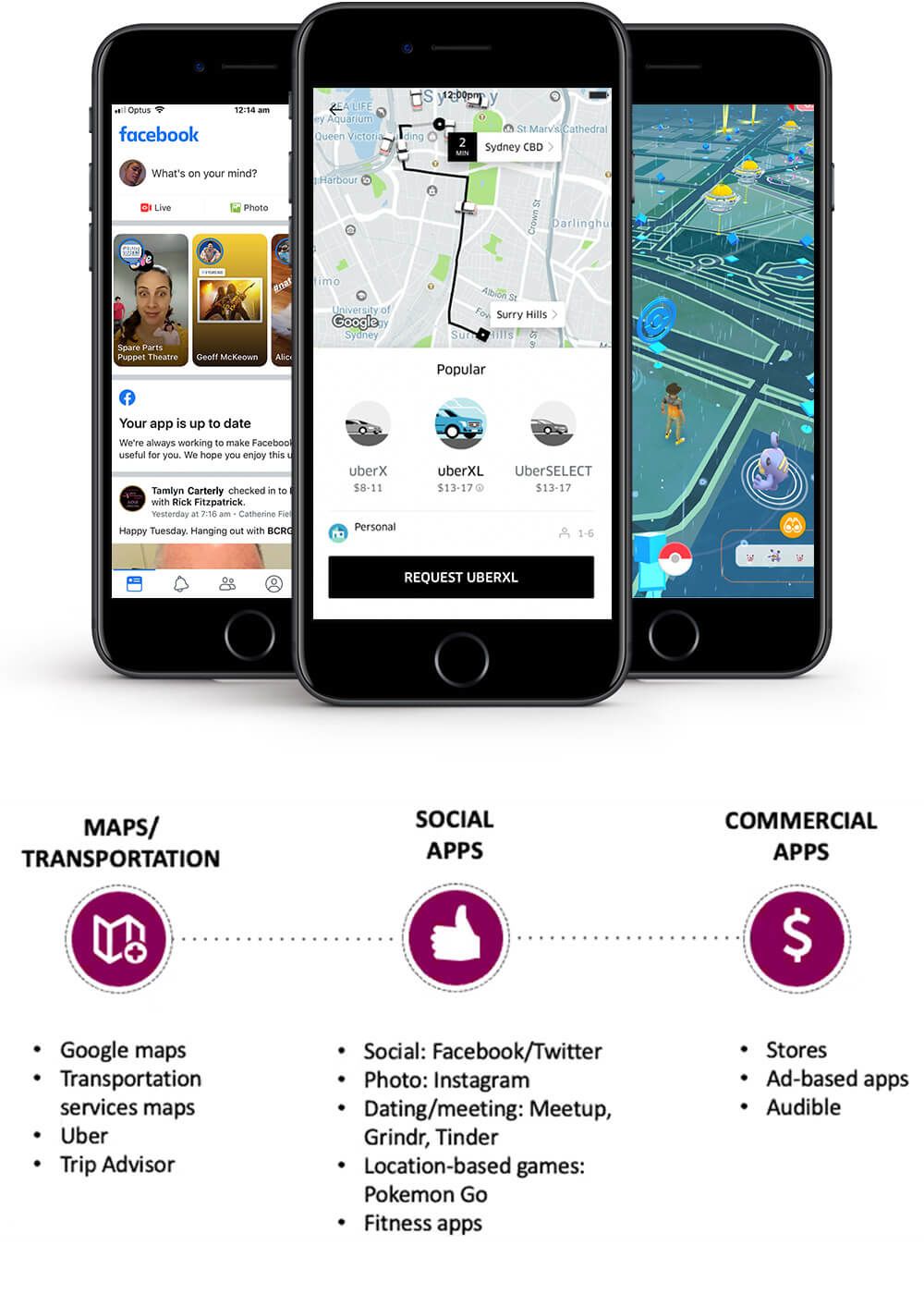

Bentley did an experiment to see the extent of how smartphones can pick up and trace movements of their users. One of her staff took a tram and train to Melbourne from Bendigo. The phone not only traced her route, but also figured out the time of the journey and what public transport she took to get to and around Melbourne.

Google Timeline of tram journey. Source: WESNET

Google Timeline of tram journey. Source: WESNET

This was recorded on Google Timeline, a feature of Google Maps. By default Google Maps saves a history of what locations a user has visited. Gaining access to Google accounts and Gmail can also give perpetrators access to calendars, Opal card, iTunes, eBay, email and government accounts.

Tracking can be as simple as being followed on social media, where sharing location information can occur inadvertently through tagging by friends or posts on social media.

For women, the impact of hacked emails and everyday accounts can be devastating.

“It’s monitoring their movements and putting them in a cage”

Sydney Legal Aid lawyer Alex Davis, who is part of the team’s Domestic Violence Unit, recounts the story of a woman who had escaped her violent partner only to be tracked by her own technology. When she rushed to catch a bus to her new job, she found her ex-partner waiting at the stop. He had hacked her Opal card and was able to access her new transport routes.

“It’s just perpetrator tactics on steroids. Giving people new ways to abuse and surveil and monitor and make a person feel option-less and to stay in that relationship,” Davis says.

“It also means leaving that relationship doesn’t have the same kind of boundaries because a person can be continually harassed no matter where they’ve gone, so they feel tethered to their ex-partner and under unrelenting harassment.”

According to the Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network, 36 per cent of the men who killed their female partner or ex-partner had a history of stalking the women they ultimately killed. The 2013 Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria survey found 97 per cent of domestic violence support workers interviewed said technology-facilitated domestic violence formed part of the abuse experienced by their clients.

“It’s monitoring their movements and putting them in a cage,” Davis says.

“It’s something that seems intangible which is why it is so hard to safety plan around it. A lot of the time people don’t even know it’s happening. It can go completely under the radar.”

LIFE OFF THE GRID: NOT THE SOLUTION

Our Watch chief executive Patty Kinnersly says for many women the temptation to go off the grid is great, but telling women to log off can isolate them from crucial support networks and put them at greater risk.

Increasingly much of our professional and personal lives are mediated online. The key, she says, is to make life online safer for women, rather than forcing them to disappear from the digital world altogether.

“Just like telling women to avoid the streets at night in a bid to keep themselves safe, telling women they need to avoid online spaces can be counter-productive,” Kinnersly says.

Tools used by women’s support service organisations to help domestic abuse survivors now extend to include a suite of digital safety education and safety training.

Chief among these are the WESNET Safe Connections phones. These smartphones donated by Telstra are handed out to domestic violence survivors by frontline services across Australia. They can also be used as second secret phones to access help and include pre-paid credit.

Bentley and her team train frontline workers on how to help women seeking support stay safe on their smartphone by turning off location services and changing passwords.

Training also covers common ways abusers misuse technology in domestic abuse situations and how to recognise it and help survivors stay safely connected. The team also covers how survivors can document and report technology abuse to the police.

As a lawyer, even Davis finds herself in the position of helping clients to go through female survivors’ phones and safety-proofing settings.

She says women fleeing violence often do not have the presence of mind to go through complex phone setting training. The possibility of human error and forgetting one step in the safety screening can have a devastating outcome.

“If I said to you today: I want you to change all of your account settings, what are the chances you will? Let alone if you are a woman who is homeless, has three kids and is scared about what will happen next?

“The problem is staying one step ahead of the technology, because every day it is changing.”

*Names have been changed.

The two-part SBS series UNDER HIS EYE examines how technology-facilitated domestic violence including Image-based abuse, location tracking, spyware and everyday digital devices are allowing perpetrators to extend new forms of coercive control over women.

CREDITS

Words by Sarah Malik

Edited by Danielle Teutsch and Natalie Hambly

Produced by Andrew Wong

Sarah Malik is Deputy Editor of SBS Voices and a 2019 Our Watch fellow. You can follow Sarah on Twitter @sarahbmalik.

HELP

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner is the national body set up to provide advice and support for Image-based abuse, including help tracking and taking down images and offering anonymity to those who report.

For information about tech abuse during domestic violence visit techsafety.org.au.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, domestic or family violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800737732 or visit www.1800RESPECT.org.au.

For more information about the WESNET Safe Connections program visit phones.wesnet.org.au.