Dancer Rudolf Nureyev was perpetually an outsider, and his mysteriousness as a human and a dancer – as depicted in the Ralph Fiennes-directed The White Crow – enabled him to become the many characters he embodied over his career. (The nickname ‘White Crow’ is akin to the label of ‘Black Sheep’: the odd one out, the curiosity in a flock.)

My grandmother was a great lover of literature, arts and ballet. When I was treated to a stay with "Nanny Moira", I slept in a room lined with books and video cassettes. Amongst the collection of dance videos were several Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn documentaries and performances. My nan and I would watch them for hours at a time. I loved the costumes, the gracefulness and synchronicity of the dancers, the impassioned faces of the dancers in close-up, the intricate stage designs and the fact that my nan had discovered a shared language with me: ballet. Nureyev and Fonteyn epitomised the art of dance to my young mind, and decades later, they still do. Only, not as the romantic creatures whose bodies twisted, swept, teetered and pirouetted with seeming effortlessness and rather, as flawed, fallible humans who suffered enormous physical aches and pains and made huge sacrifices to pursue their profession. Fiennes’ film is divided into the three major periods of Nureyev’s life, based on Julie Kavanagh’s biography and translated into a script by English playwright, theatre, film director, and screenwriter David Hare. Hare’s own play, “Judas Kiss” was a harrowing exploration of Oscar Wilde’s scandalous relationship with a young Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. The decline of great men, punished for their sexuality, their refusal to feel show shame in expressing their sexual desires and their bodies, is ground Hare has covered before – though not in “White Crow”. However, Hare does not directly address Nureyev’s sexuality and the many relationships he likely had with men prior to defecting from Russia. Nureyev’s sexuality, and the rumours and assumptions made by Russian authorities around it based on his profession, were surely major factors in his desire to escape Russia and his Muslim-Russian roots. Fiennes’ diplomatic, if flimsy, reasoning was that the film ends with Nureyev’s defection and thus his sexuality had not been explicitly clear to that point. “Clearly, later in his life he was an unapologetically gay man, but where our story finishes with his defection, I think we are portraying a man who is learning who he is,” Fiennes, who also plays the role of ballet master Alexander Pushkin in the film, told .

Fiennes’ film is divided into the three major periods of Nureyev’s life, based on Julie Kavanagh’s biography and translated into a script by English playwright, theatre, film director, and screenwriter David Hare. Hare’s own play, “Judas Kiss” was a harrowing exploration of Oscar Wilde’s scandalous relationship with a young Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. The decline of great men, punished for their sexuality, their refusal to feel show shame in expressing their sexual desires and their bodies, is ground Hare has covered before – though not in “White Crow”. However, Hare does not directly address Nureyev’s sexuality and the many relationships he likely had with men prior to defecting from Russia. Nureyev’s sexuality, and the rumours and assumptions made by Russian authorities around it based on his profession, were surely major factors in his desire to escape Russia and his Muslim-Russian roots. Fiennes’ diplomatic, if flimsy, reasoning was that the film ends with Nureyev’s defection and thus his sexuality had not been explicitly clear to that point. “Clearly, later in his life he was an unapologetically gay man, but where our story finishes with his defection, I think we are portraying a man who is learning who he is,” Fiennes, who also plays the role of ballet master Alexander Pushkin in the film, told . Nureyev was born on a Trans-Siberian train near Siberia to Tatar Muslim parents in 1938, shortly before World War II. In his twenties, despite KGB efforts to prevent it, he defected from the Soviet Union. On a trip to Paris as part of the Kirov ballet company, he experienced the sort of freedom he’d been ignorant to in Russia. The KGB reported back to Moscow that the dancer ought to be returned for allegedly being a frequent patron at gay clubs and bars and spending much of his time with non-Soviet colleagues. Instead, Nureyev recruited the assistance of French police and diplomats to enable him to apply for asylum and remain in Paris. It was the beginning of a life of both freedom and the constant push-and-pull of his country, his family, and the question of what home meant. As a Tatar, Nureyev never saw himself as Russian but as an outsider, even in the country of his birth.

Nureyev was born on a Trans-Siberian train near Siberia to Tatar Muslim parents in 1938, shortly before World War II. In his twenties, despite KGB efforts to prevent it, he defected from the Soviet Union. On a trip to Paris as part of the Kirov ballet company, he experienced the sort of freedom he’d been ignorant to in Russia. The KGB reported back to Moscow that the dancer ought to be returned for allegedly being a frequent patron at gay clubs and bars and spending much of his time with non-Soviet colleagues. Instead, Nureyev recruited the assistance of French police and diplomats to enable him to apply for asylum and remain in Paris. It was the beginning of a life of both freedom and the constant push-and-pull of his country, his family, and the question of what home meant. As a Tatar, Nureyev never saw himself as Russian but as an outsider, even in the country of his birth.  It is as Nureyev arrives in this new period of his life – geographically, professionally and emotionally – that his story becomes truly fascinating. He is an expatriate, a man without family, a dancer at his physical peak and he is trying to establish his identity after a decade or so of surveillance and threat.

It is as Nureyev arrives in this new period of his life – geographically, professionally and emotionally – that his story becomes truly fascinating. He is an expatriate, a man without family, a dancer at his physical peak and he is trying to establish his identity after a decade or so of surveillance and threat.

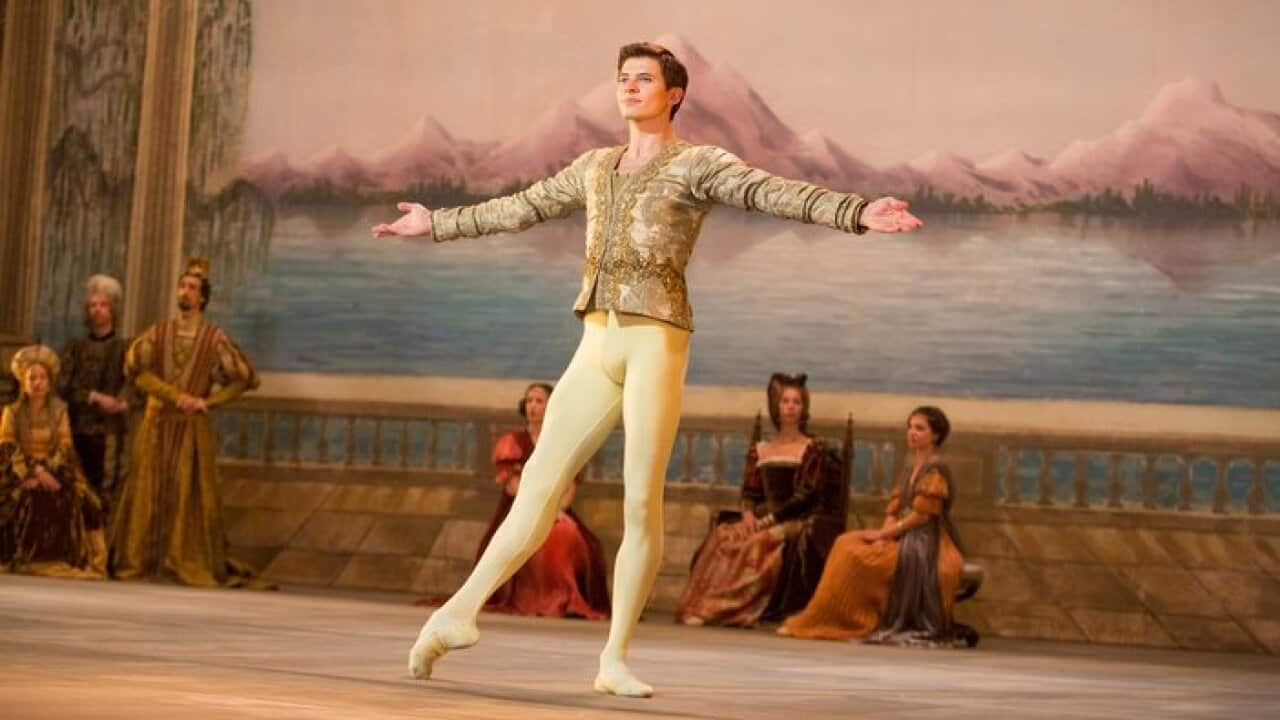

Oleg Ivenko as Rudolf Nureyev in 'The White Crow'. Source: Entertainment One

Ralph Fiennes in 'The White Crow'. Source: Entertainment One

'The White Crow' captures key early moments in Nureyev's life. Source: Jessica Forde

As anyone who has felt like an outsider knows, the desire to belong and the relentless self-inquiry as to why we don’t fit in, or why we can’t be like everyone around us provides an exceptional drive and fiery ambition to prove that we do belong here. Even in his 40s, burdened with chronic back pain and an ankle spur that made dancing painful, Nureyev still told an interviewer that of the 250 performances he’d given in that year to date, only three were good.

The impassioned facial expressions, in which his chiselled cheekbones and haunted eyes conveyed theatrical expressions of grief, yearning, lovesick desire and fury that as a child, I was enthralled by, made tragic sense to me as an adult. He did know all those states of being, and for all the lovers he had, the famous friends and the international acclaim, by the time of Nureyev’s premature death at 53 he had still not found peace or the answers to his perennial questions of identity and belonging.

Though he played heroes, princes, and young romantics onstage, his own life was infinitely more intriguing. For me, he is inextricably partnered with Margot Fonteyn. The onstage partnership he shared with her went beyond the stage lights. The pair were spiritually – if not sexually – entwined. Fonteyn died of ovarian cancer only two years before Nureyev died, reportedly of AIDS. To have witnessed their pas de deux in decades earlier, that they would be eternally dancing to one another’s rhythms in life and death seems inevitable. That’s another movie, for another time.

In the meantime, The White Crow, with its aesthetic appeal – not least in Oleg Ivenko as Nureyev and the exceptionally (almost supernaturally) talented Sergei Polunin as Yuri Soloviev, with Fiennes as Alexander (Aleksandr) Pushkin – gives us a glimpse of what created the perpetual outsider.

See The White Crow Friday, 24 December at 8.30pm on SBS World Movies, part of the Summer Of Discover collection running Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights.