Tens of thousands of Australians have taken to the streets over the past fortnight to march against police brutality.

The protests followed the death of US man George Floyd during his arrest by Minneapolis police and drew particular attention to Australia’s own history of Indigenous deaths in custody.

While it is too early to tell what real change will stem from the local movement, reform is already underway overseas; France has banned its police from using the chokehold and Minneapolis has voted to dismantle and rebuild its police force.

Here are four times mass protests have changed Australia for the better.

Sydney’s first Mardi Gras, 1978

Today, the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras draws tens of thousands people to Sydney’s Oxford Street in an annual celebration of LGBTIQ+ communities.

But the city’s first Mardi Gras was a very different affair.

A morning march on 24 June 1978 was organised by Sydney's Gay Solidarity Group to commemorate the anniversary of the .

It would be followed by a forum to discuss the legal rights of gay and lesbian Australians.

But on the night of 24 July, thousands turned up to walk together through the streets towards Oxford Street in what would later be dubbed a 'Mardi Gras'.

Although organisers had a permit allowing them to protest, they were quickly met with disapproving police, who violently suppressed the demonstrators and made 53 arrests.

While the march saw an ugly end, Charles Sturt University public ethics professor and author Clive Hamilton said the events on that day were significant.

“Those very early protesters who came out as gay people - the courage of those people was astonishing because of the social hostility towards them and the real danger they were in,” he tells SBS News.

“It was tremendously courageous for those young people and that actually galvanised the whole movement. By the ‘90s, a contingent of police officers were marching.”

Later protests would follow, bringing gay rights into the broader public’s consciousness. Six years later in 1984, NSW decriminalised homosexuality.

The Wave Hill walk-off, 1966

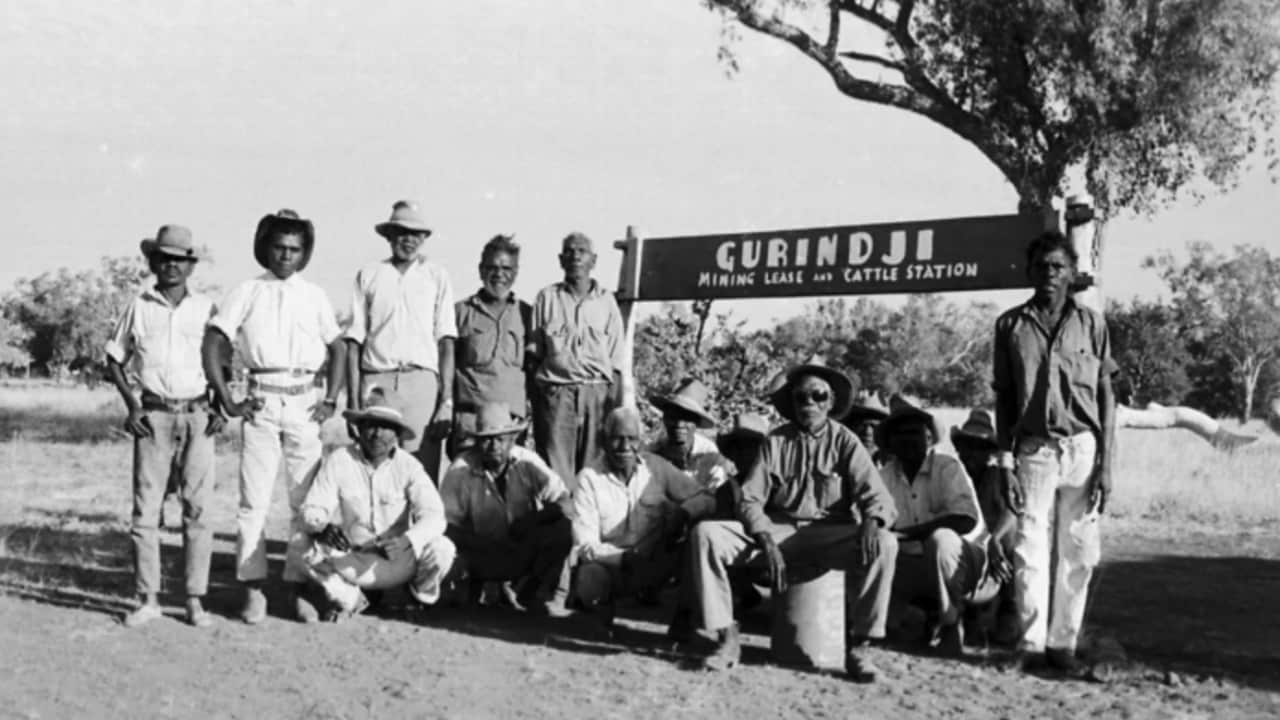

On 23 August 1966, 200 Gurindji stockmen and their families made national headlines when they walked off the Wave Hill pastoral station in the Northern Territory to demand better working conditions.

Led by Vincent Lingiari, and quickly turned their attention to getting their traditional lands back in a move that fuelled the Aboriginal land rights movement.

The Wave Hill walk-off lasted seven years.

Almost a decade later in 1976, then-Prime Minister Gough Whitlam visited Wave Hill to return more than 3,000 square kilometres of land to the Gurindji people, pouring a symbolic handful of red soil into Mr Lingiari's hands.

“Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people and I put into your hands part of the earth itself as a sign that this land will be the possession of you and your children forever,” Mr Whitlam said. Mr Lingiari responded: “Let us live happily together as mates, let us not make it hard for each other… We want to live in a better way together, Aboriginals and white men. Let us not fight over anything. Let us be mates.”

Mr Lingiari responded: “Let us live happily together as mates, let us not make it hard for each other… We want to live in a better way together, Aboriginals and white men. Let us not fight over anything. Let us be mates.”

Gough Whitlam pours a soil in Vincent Lingiari's hands, marking the return of the Gurindji peoples' land. Source: Mervyn Bishop

It was the first time the federal government had returned land to an Aboriginal community.

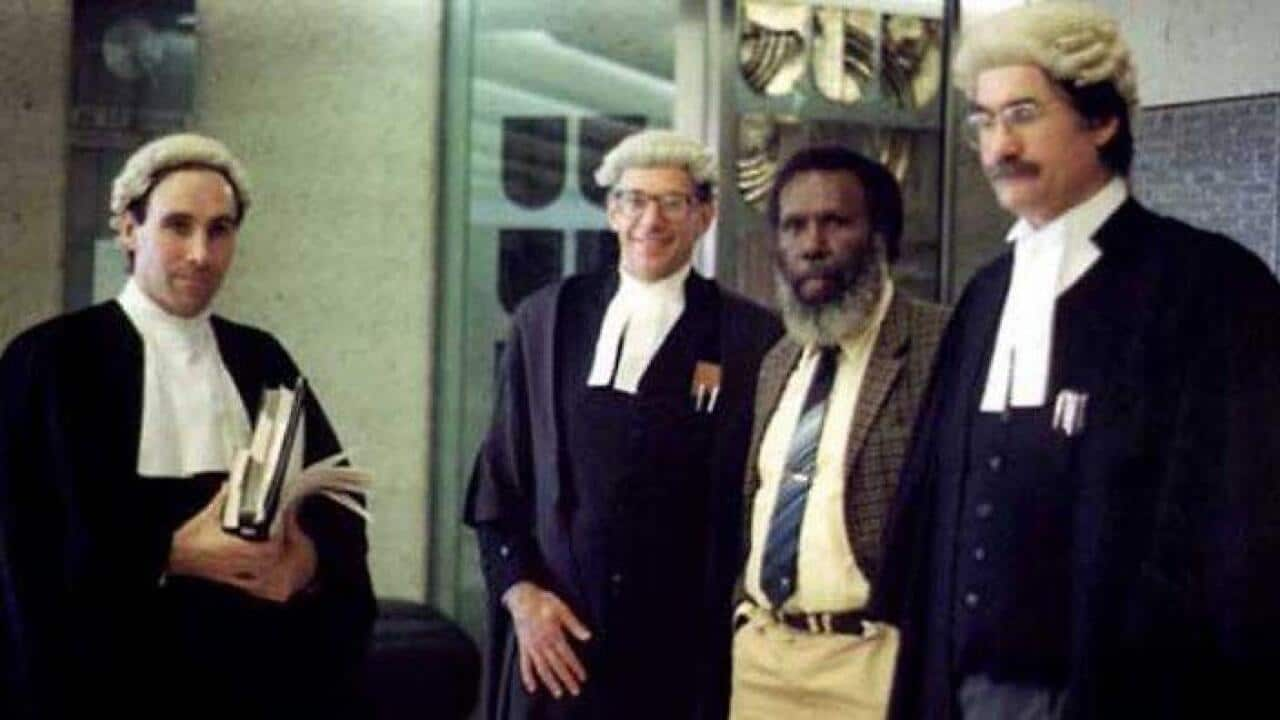

Sixteen years later, Torres Strait Islander Eddie Koiki Mabo would go on to make history in the High Court in 1992, overturning the terra nullius declaration - that Australia was once land belonging to no-one.

According to the latest numbers from the National Native Title Tribunal, there have since been 496 native title determinations.

The Franklin Blockade, 1982

The years-long struggle to save the breathtaking Franklin River in Tasmania was arguably the beginning of Australia’s modern environmental movement.

In December 1982, led by soon-to-be Greens Party founder Bob Brown, 6,000 people travelled to the riverside town of Strahan in a bid to stop the Franklin from being dammed. More than 1,200 protesters were arrested over the following three months as the activists did everything they could to block construction equipment from the area.

More than 1,200 protesters were arrested over the following three months as the activists did everything they could to block construction equipment from the area.

Protesters hold their ground on the Franklin River in February 1983. Source: Jerry de Gryse / National Library of Australia

The protests quickly drew the nation’s attention to the natural beauty that was at risk of being lost if plans to build the dam went ahead. When Bob Hawke and the Labor Party won the federal election a few months later in March 1983, they quickly passed legislation to protect the south-west of Tasmania, and the Franklin Blockade was deemed a success.

When Bob Hawke and the Labor Party won the federal election a few months later in March 1983, they quickly passed legislation to protect the south-west of Tasmania, and the Franklin Blockade was deemed a success.

A poster calling for donations to the campaign to stop the damming of the Franklin River. Source: Peter Dombrovskis / National Library of Australia

The campaign also received international attention with UNESCO adding the river to its list of World Heritage sites during the blockade.

The Tent Embassy, 1972

Professor Hamilton says the Tent Embassy is proof that, sometimes, the most spontaneous actions can mark the beginning of a mass movement.

On 25 January 1972, four young Aboriginal activists had gathered in Sydney when one commented that, since they were being treated as aliens on their own land, they should set up an embassy in Canberra.

“The next day, they drove into Canberra, they got a tent, they got some cardboard and paint and they made some signs,” he says. “Within days it took off and attracted so much support. And then older Aboriginal activists who were initially quite dismissive of these younger ‘black power’ activists realised it was a watershed moment and they started to arrive from all over Australia as well.”

“Within days it took off and attracted so much support. And then older Aboriginal activists who were initially quite dismissive of these younger ‘black power’ activists realised it was a watershed moment and they started to arrive from all over Australia as well.”

The Tent Embassy on its very first day - 26 January 1972. Source: National Museum of Australia

Within a few months, the activists had arranged to meet with Labor politicians, including soon-to-be prime minister Gough Whitlam. “I think they started to help shift the Labor party to a far more determined position of acting on Indigenous rights,” Professor Hamilton says.

“I think they started to help shift the Labor party to a far more determined position of acting on Indigenous rights,” Professor Hamilton says.

Then-Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam visiting the Tent Embassy. Source: National Archives Australia

“Then, when the Whitlam Government came along, they took some landmark action on Indigenous rights.”

Over the next 20 years, and has sat permanently on the lawns of Old Parliament House since 1992.

What makes a protest movement successful?

The number of people in the streets is not always tantamount to success in Australian protest movements.

As time has gone on, Professor Hamilton says it has become harder and harder to create real change by protesting. “Back in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, the protest was a very radical act - to get out on the streets was to stick two fingers up at authority,” he says.

“Back in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, the protest was a very radical act - to get out on the streets was to stick two fingers up at authority,” he says.

An estimated 250,000 protesters marched through Sydney's CBD on 16 February 2003 against Australia's involvement in Iraq. Source: DIG

“So authority felt extremely threatened by people getting out on the streets. They don’t any more. It’s become habitual - politicians know how to deal with it, how to react, and it’s become normalised.”

Professor Hamilton said that was exactly what happened in 2003 when more than 500,000 people around Australia marched against the Iraq War in what became the biggest protests the country had ever seen. “Absolutely nothing happened, because Prime Minister Howard and the political machine of the Liberal Party decided ‘This isn’t going to influence our votes, so we can safely ignore it’,” he says.

“Absolutely nothing happened, because Prime Minister Howard and the political machine of the Liberal Party decided ‘This isn’t going to influence our votes, so we can safely ignore it’,” he says.

Student activists hold a 'solidarity sit-down' outside of the office of the Liberal Party of Australia in Sydney last November. Source: AAP

More recently, Australia’s mass School Strike 4 Climate protests have seen hundreds of thousands of school students across the country walk out of the classroom to fight for climate action.

“If you’re going to have a massive march, you’ve got to follow up,” Professor Hamilton says.

“A march in and of itself is very unlikely to have any impact. It’s got to be a long-running campaign that draws in all kinds of elements of society in order to convince the government, or governments, that they have to change.”