Italian

Diving sound effects

Una delle attrazioni più importanti d’Australia è la Grande Barriera Corallina, una delle sette meraviglie naturali del mondo, che si estende per oltre 2.300 chilometri in un’area di approssimativamente 344.400 chilometri quadrati.

Come tutte le distese di corallo, è come una foresta pluviale per la vita marina che fornisce cibo agli uomini e agli animali del mare, offrendo protezione vicino alla costa per le comunità costiere e lavori per le economie turistiche.

Ma quando le temperature dell’oceano salgono, il corallo rilascia la sua alga simbiotica che fornisce i nutrienti e dona i suoi vibranti colori.

Il corallo diventa bianco - un processo chiamato sbiancamento – e può ammalarsi rapidamente e morire.

La Grande Barriera Corallina ha subito l’evento di sbiancamento più diffuso mai registrato nel 2020, con gravi episodi di sbiancamento scoperti nello Stretto di Torres nel nord fino ai confini meridionali della Barriera.

Crawford Drury è un ecologo del corallo e ricercatore principale alla University of Hawaii:

"Corals are threatened worldwide by a lot of stressors, but increasing temperatures are probably the most severe. And so that's what our focus is on, is working with parents that are really thermally tolerant."

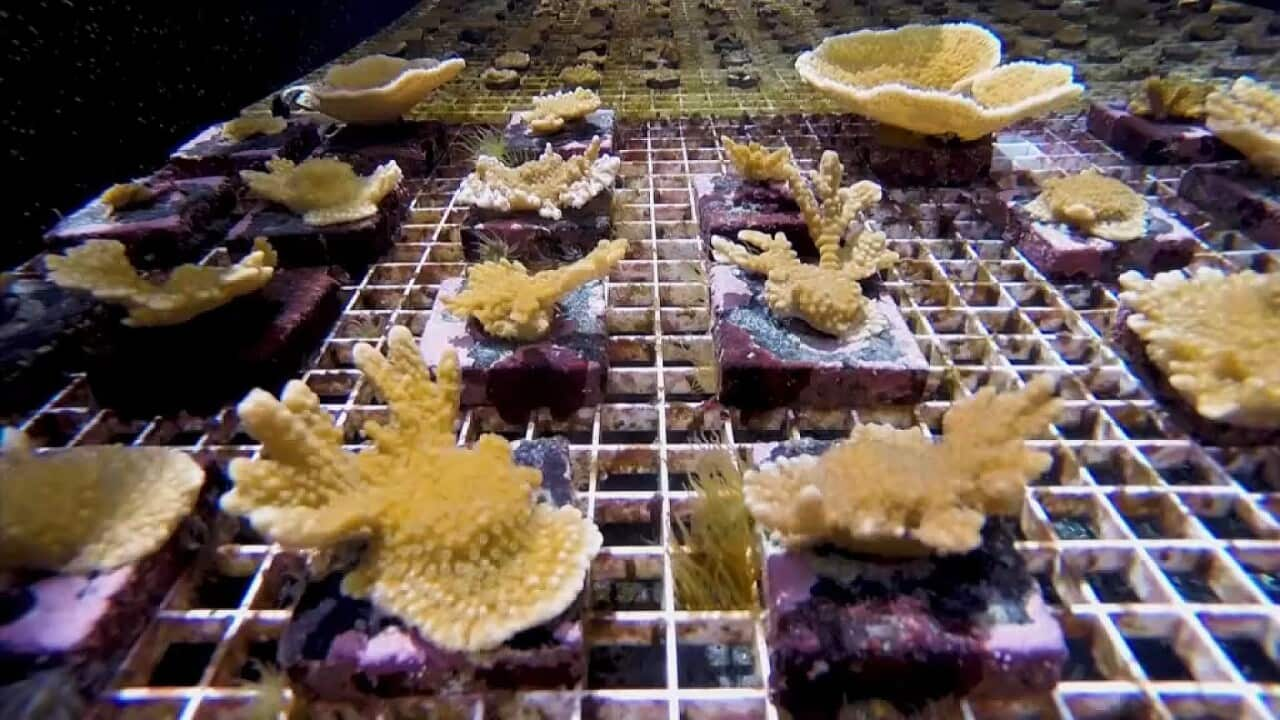

Negli scorsi cinque anni, ricercatori in Hawaii e Australia hanno condotto esperimenti per cercare di accelerare l’orologio evolutivo del corallo per generare “super coralli” che possano sopportare meglio gli impatti del riscaldamento globale.

Hanno registrato dei successi iniziali, e Crawford Drury ritiene che ora siano pronti a piantare nell’oceano ibridi selezionati insieme ad altri coralli formati in laboratorio per vedere se possono sopravvivere in natura.

"So the basic idea behind selective breeding, which has been used by people for millennia, is that if you know a characteristic of a parent and you preferentially breed that parent that you can either amplify or increase the trait you care about."

Mentre il corallo si riproduce, gli scienziati raccolgono le masse gelatinose che odorano di pesce e le mettono in provette.

La chiamano “evoluzione assistita”.

Madeleine van Oppen, una genetista ecologica all’Australian Institute of Marine Science dell’Università di Melbourne che pubblicò dapprima la teoria con la sua collega Ruth Gates alle Hawaii, ricorda che all’inizio non venne accettata diffusamente quando venne proposta.

"There was a lot of ethical comments like, Oh, you think you're playing god by intervening with the reef. Well, you have already intervened with the reef for very long periods of time. All we're trying to do is to repair the damage. You know, people often don't see it that way. There's no part of the ocean where we cannot detect human influence. So."

Gli scienziati proposero di portare i coralli in un laboratorio per aiutarli ad evolvere in animali più tolleranti al calore.

E l’idea attirò il co-fondatore di Microsoft Paul Allen, che finanziò la prima fase della ricerca e la cui fondazione ancora sostiene il programma.

La dottoressa Gates purtroppo morì di cancro al cervello nel 2018, ma Madeleine Van Oppen sostiene che il lavoro sia continuato – nonostante diverse resistenze.

"Yeah, there was definitely quite a bit of scepticism when we proposed the idea. Many people focused on the risks. We got a lot of comments like, 'Oh, you will lose genetic diversity and you will be worse off if you implement the methods that you propose.'"

Van Oppen ha dichiarato che invece che editare i geni o creare qualcosa di innaturale, i ricercatori stanno solamente accelerando quello che già potrebbe succedere nell’oceano.

Nessuno sta suggerendo che l’evoluzione assistita da sola salverà i coralli del mondo.

L’idea fa parte di un ventaglio di misure, con proposte che vanno dalla creazione di schermi per il corallo al pompaggio di acqua più fredda dalle profondità dell’oceano sul corallo che si sta riscaldando troppo.

Il vantaggio nel piantare coralli più resistenti è che dopo una o due generazioni dovrebbero diffondere naturalmente i loro tratti, senza troppo intervento umano.

Madeleine Van Oppen e i suoi colleghi hanno già introdotto alcuni coralli con le alghe simbiotiche modificate sulla Grande Barriera Corallina.

Gli scienziati ritengono di essere in una corsa contro il tempo per salvare i coralli, con le acque degli oceani del mondo in continuo riscaldamento.

English

Diving sound effects

One of Australia's biggest attractions is the Great Barrier Reef, one of the seven wonders of the natural world, stretching for over 2,300 kilometres over an area of approximately 344,400 square kilometres.

Like all coral reefs, it's like a sea-life rain forest, providing food for humans and marine animals, shoreline protection for coastal communities and jobs for tourist economies.

But when ocean temperatures rise, coral releases its symbiotic algae that supply nutrients and impart its vibrant colors.

The coral turns white - a process called bleaching - and can quickly become sick and die.

The Great Barrier Reef experienced its most widespread bleaching event on record in 2020, with severe bleaching found from the Torres Strait in the north, down to the Reef’s southern boundary.

Crawford Drury is a coral ecologist, and principal investigator at the University of Hawaii:

"Corals are threatened worldwide by a lot of stressors, but increasing temperatures are probably the most severe. And so that's what our focus is on, is working with parents that are really thermally tolerant."

For the past five years, researchers in Hawaii and Australia have been conducting experiments to try to speed up coral's evolutionary clock to breed "super corals" that can better withstand the impacts of global warming.

They have had initial success and Crawford Drury says now they’re getting ready to plant selectively bred and other lab-evolved corals back into the ocean to see if they can survive in nature.

"So the basic idea behind selective breeding, which has been used by people for millennia, is that if you know a characteristic of a parent and you preferentially breed that parent that you can either amplify or increase the trait you care about."

As the coral spawn, the scientists scoop up the fishy-smelling blobs and put them in test tubes.

They're calling it 'assisted evolution'.

Madeleine van Oppen, an ecological geneticist at the University of Melbourne's Australian Institute of Marine Science - who first published the theory with her colleague Dr Ruth Gates in Hawaii - says it was not widely accepted when it was first proposed.

"There was a lot of ethical comments like, Oh, you think you're playing god by intervening with the reef. Well, you have already intervened with the reef for very long periods of time. All we're trying to do is to repair the damage. You know, people often don't see it that way. There's no part of the ocean where we cannot detect human influence. So."

The scientists proposed bringing corals into a lab to help them evolve into more heat-tolerant animals.

And the idea attracted Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who funded the first phase of research and whose foundation still supports the program.

Sadly, Dr Gates died of brain cancer in 2018 - but Madeleine Van Oppen says the work has continued - despite some resistance.

"Yeah, there was definitely quite a bit of scepticism when we proposed the idea. Many people focused on the risks. We got a lot of comments like, 'Oh, you will lose genetic diversity and you will be worse off if you implement the methods that you propose.'"

She says rather than editing genes or creating anything unnatural, researchers are just speeding up what could already happen in the ocean.

No one is proposing assisted evolution alone will save the world's reefs.

The idea is part of a suite of measures – with proposals ranging from creating shades for coral to pumping cooler deep-ocean water onto reefs that get too warm.

The advantage of planting stronger corals is that after a generation or two, they should spread their traits naturally, without much human intervention.

Madeleine Van Oppen and her colleagues have already put some corals with modified symbiotic algae back on the Great Barrier Reef.

With the world's oceans continuing to warm, scientists say they are up against the clock to save reefs.

Report by Allan Lee.