Italiano

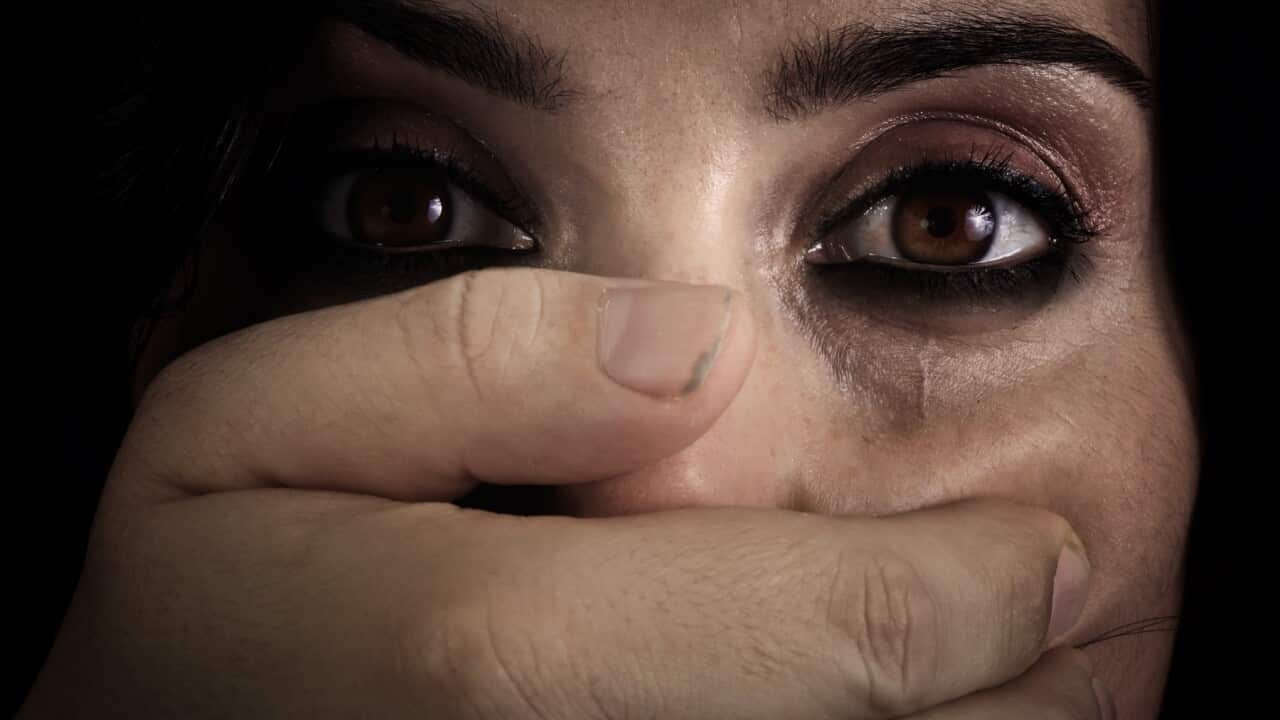

La famiglia di Sanaa Hamid proviene dall'Eritrea, nell'Africa orientale, ma lei è nata in Sudan.

Nel 1998, quando aveva 15 anni, è arrivata in Australia come rifugiata insieme alla sorella maggiore.

Qualche anno dopo, il padre le ha organizzato un matrimonio.

Non aveva mai visto una foto di quest'uomo e non sapeva nulla della sua personalità, ma le fu detto che doveva stare con lui.

Sono stati sposati per 19 anni e hanno avuto sei figli, ma lui è poi diventato violento nei suoi confronti.

Alla fine, con il sostegno del Victoria's Centre of Advancing Women, Sanaa ha divorziato dal marito e ha trovato la salvezza.

"One of my friends, he told me come to Sunshine. We have a beautiful centre. They can help you and we can have coffee and they have courses to study. Don't sit by yourself at home. I said, I don't want to talk to anyone. I don't want to go out into the community, but I'll try to come. I like the place and I like the help, you know, the women share their stories together."

Il centro è stato fondato da Samia Baho, una donna eritrea giunta in Australia come rifugiata negli anni Settanta.

Ha iniziato a lavorare come addetta alle pulizie, ma ha proseguito gli studi in ambito sociale, sanitario e giuridico e da allora è una ricercatrice sulle esigenze delle donne rifugiate.

Durante la pandemia di Covid-19, Baho ha notato un aumento della violenza familiare, che l'ha portata a fondare il Centre of Advancing Women nel 2020.

Secondo Baho, i rifugiati spesso devono affrontare barriere linguistiche e culturali quando cercano di ottenere aiuto.

La maggior parte delle 19 volontarie del centro sono arrivate in Australia come rifugiate da contesti molto diversi, possiedono lauree specialistiche in assistenza sociale e salute e, tra di loro, parlano 11 lingue diverse.

Baho ha affermato che l'esperienza vissuta dei suoi volontari è ciò che rende il centro diverso.

"We have the culture, we have the similarity, so automatically they feel connected, automatically they feel, not just we listen to them and believe them, where most agencies or most services do, but we understand them. Because we are from them."

Per Baho molte organizzazioni con buone intenzioni cercano di aiutare le donne rifugiate, ma spesso le donne possono diventare dipendenti da questi servizi.

Il modello del suo centro mira a fornire alle donne la formazione necessaria per comprendere i sistemi australiani e sostenersi da sole.

"But also the women, they have to know how to own their own problems and how to learn how to solve those problems...We're talking about women from, you know, marginalised, very small communities like for example, from African refugee backgrounds. We're talking about the Middle East, Iraqi and all of these. And then also, we have Indians, they come in as you know, under the spouse visa and all. So it's very important to know about difficulties from their own cultures."

Per molte donne che si rivolgono al centro, la minaccia di espulsione viene usata come controllo coercitivo.

All'inizio di quest'anno, il governo Albanese ha dichiarato la violenza domestica una crisi nazionale in Australia e ha nominato un gruppo di esperti per rivedere il Piano Nazionale per porre fine alla violenza contro le donne, gruppo in vigore dal 2022.

Sia il piano originale che la recente revisione citano l'uso delle leggi sull'immigrazione nei casi di violenza domestica che coinvolgono donne rifugiate.

Ma la professoressa della Monash University Marie Segrave ha affermato che non si fa ancora abbastanza.

“What we are seeing are small changes that are heralded as advances, but I would argue they're not really changing the fact that the migration system, for example, really is sustaining the conditions that domestic and family violence thrives in. And it continues to kind of ensure that that their sponsors or other people can kind of leverage the control of the migration system over them so they can threaten them with deportation, of dubbing them into immigration, of separating people from their children.”

Un portavoce del Dipartimento dei Servizi Sociali ha detto che il governo è impegnato a porre fine alla violenza di genere e ha investito 4,4 miliardi di dollari a settembre per realizzare il Piano Nazionale.

Per Baho, le donne rifugiate che forniscono servizi professionali sono spesso discriminate.

"I'm talking about skills and qualifications in the way, you know, like, Australia and Western...I personally heard many times, oh, you don't have the training, oh, you don't have the skills. Not because they ask what skills and what training we have, but just because we look different. Yes, we look black. Yes, some of us wear the scarves... when they look at us like this, what do you think? How do you think they will deal with the women?"

Baho ha dichiarato che è necessario fare di più a livello politico, e la politica dovrebbe essere informata da coloro che hanno vissuto l'esperienza.

"They have to come and have a look at other models that are working and improving. I think I could say with all the confidence, if it's not the only, we are one of the very few offering pathways for women from being a victim to achieving in the areas of training and employment...They need to move away from seeing us as a liability. We are an asset to the society."

L'anno scorso il centro ha offerto corsi di lavoro sociale.

A novembre si è tenuta una cerimonia di consegna dei diplomi presso il Parlamento del Victoria.

La figlia di Sanaa era tra il pubblico.

"Oh my God, I'm the only one who danced like a monkey dancing. I was so happy... And my kid was so proud. My daughter, she said I'm going to graduate like you one day, Mum. She wants to be a psychologist in the future."

Baho ha detto che il corso è attualmente in fase di revisione, ma una volta ottenuti i finanziamenti, spera di offrire altri corsi nel 2025.

Secondo Baho, gestire un centro di sostegno alla violenza familiare è un lavoro impegnativo, perché ci sono sfide all'interno della comunità e del sistema, ma vedere le donne prendere in mano la propria vita la gratifica.

"For us to pick up the women that fell in between the cracks, and their life being destroyed, and pick them up and build them. That's music to our ears when they say they are out of focus."

Inglese

Sanaa Hamid's family is from Eritrea in East Africa, but she was born in Sudan.

In 1998 when she was 15, she came to Australia as a refugee with her older sister.

A few years later, her father arranged a marriage for her.

She'd never seen a photo of this man and knew nothing about his personality, but was told she had to stay with him.

They were married 19 years and had six children, but he became violent towards her.

Eventually, with the support of Victoria's Centre of Advancing Women, Sanaa divorced her husband and found safety.

"One of my friends, he told me come to Sunshine. We have a beautiful centre. They can help you and we can have coffee and they have courses to study. Don't sit by yourself at home. I said, I don't want to talk to anyone. I don't want to go out into the community, but I'll try to come. I like the place and I like the help, you know, the women share their stories together."

The centre was founded by Samia Baho ba-ho, an Eritrean woman who came to Australia as a refugee in the 1970s.

She began working as a cleaner but went on to study in areas of social work, women's health and law, and has since been a researcher on the needs of refugee women.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Ms Baho noticed an increase in family violence, which led to her starting the Centre of Advancing Women in 2020.

She says refugees often face language and cultural barriers when trying to get help.

Most of the centre's 19 volunteers came to Australia as refugees from many different backgrounds, possess postgraduate degrees in social work and health, and between them, speak 11 different languages.

Ms Baho says the lived experience of her volunteers is what makes the centre different.

"We have the culture, we have the similarity, so automatically they feel connected, automatically they feel, not just we listen to them and believe them, where most agencies or most services do, but we understand them. Because we are from them."

Ms Baho says many well-intentioned organisations try to help refugee women but often women can become dependent on these services.

She says her centre's model aims to give women the training they need to understand Australian systems and support themselves.

"But also the women, they have to know how to own their own problems and how to learn how to solve those problems...We're talking about women from, you know, marginalised, very small communities like for example, from African refugee backgrounds. We're talking about the Middle East, Iraqi and all of these. And then also, we have Indians, they come in as you know, under the spouse visa and all. So it's very important to know about difficulties from their own cultures."

For many women that come to the centre, the threat of deportation is used as coercive control.

Earlier this year, the Albanese Government declared domestic violence a national crisis in Australia and appointed an expert panel to review the National Plan to End Violence Against Women, which has been in place since 2022.

Both the original plan and the recent review mention the use of immigration laws in domestic violence cases involving refugee women.

But Monash University Professor Marie Segrave says still not enough is being done.

“What we are seeing are small changes that are heralded as advances, but I would argue they're not really changing the fact that the migration system, for example, really is sustaining the conditions that domestic and family violence thrives in. And it continues to kind of ensure that that their sponsors or other people can kind of leverage the control of the migration system over them so they can threaten them with deportation, of dubbing them into immigration, of separating people from their children.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Social Services says the government is committed to ending gender-based violence and has invested $4.4 billion ((in September)) to deliver on the National Plan.

Ms Baho says refugee women providing professional services are often discriminated against.

"I'm talking about skills and qualifications in the way, you know, like, Australia and Western...I personally heard many times, oh, you don't have the training, oh, you don't have the skills. Not because they ask what skills and what training we have, but just because we look different. Yes, we look black. Yes, some of us wear the scarves... when they look at us like this, what do you think? How do you think they will deal with the women?"

Ms Baho says more needs to be done at a policy level, which should be informed by those with lived experience.

"They have to come and have a look at other models that are working and improving. I think I could say with all the confidence, if it's not the only, we are one of the very few offering pathways for women from being a victim to achieving in the areas of training and employment...They need to move away from seeing us as a liability. We are an asset to the society."

Last year the centre offered social work courses.

In November, they had a graduation ceremony at the Parliament of Victoria.

Sanaa's daughter was in the audience.

"Oh my God, I'm the only one who danced like a monkey dancing. I was so happy... And my kid was so proud. My daughter, she said I'm going to graduate like you one day, Mum. She wants to be a psychologist in the future."

Ms Baho says the course is currently under review, but once funding is secured, they hope to offer more courses in 2025.

She says it's a big job running a family violence support centre, as there are challenges from within the community and the system, but seeing women take charge of their own lives makes it worth it.

"For us to pick up the women that fell in between the cracks, and their life being destroyed, and pick them up and build them. That's music to our ears when they say they are out of focus."