Italiano

Dopo un'importante stagione di cova, ambientalisti come Billy Collett festeggiano i progressi compiuti per salvare dall'estinzione le specie di tartarughe d'acqua dolce australiane a rischio.

La sua organizzazione, Aussie Ark, ha allevato tre specie diverse presso l'Australian Reptile Park di Somersby, nel New South Wales.

"So exciting. 48 Hunter River turtle eggs, 39 Bell's turtle eggs, and a whopping 85 Manning River turtle eggs. We will care and look after these beautiful little hatchlings until they're bigger and stronger, and then we can return them back out into the wild rivers where they belong."

Secondo l'esperto, programmi come questo arrivano in un momento in cui questi antichi animali sono minacciati in modo unico.

"These turtles literally date back millions of years to the age of the dinosaurs and now they're facing extinction, which is really upsetting. So, that's why this project is absolutely critical for the survival of the species."

Ma perché queste tartarughe sono minacciate?

Martin Dillon è il Senior Land Services Officer del Northern Tablelands Local Land Services e dirige un'operazione per proteggere la popolazione locale di tartarughe di Bell, che si trovano esclusivamente nel nord del New South Wales.

Secondo lui, negli ultimi anni la specie è stata messa in pericolo da predatori invasivi.

"European foxes are raiding almost all of their nests. So Bell's turtles lay their eggs buried in the stream bank, really close to the water's edge, actually within a few meters. And they're naive to foxes. They haven't evolved with foxes. And foxes are just super efficient and they train their cubs to patrol the riverbanks during the nesting season, find those packets of protein and just eat them up. And so what happens is, although turtles are long lived and they're really tough and they're really robust, there's not enough recruitment to sustain the population."

Secondo la dottoressa Lou Streeting dell'Università del New England, attualmente più del 95% dei nidi di tartaruga di Bell vengono razziati, in parte a causa dell'approccio genitoriale particolarmente scevro di attenzioni delle tartarughe.

"With turtles, they don't have maternal care, so they deposit their eggs on the riverbank and the female returns to the water. The eggs are very vulnerable to foxes."

Dillon afferma che il suo team ha due approcci diversi per proteggere le tartarughe, il primo dei quali prevede di sottrarre le uova alla minaccia delle volpi.

"Borrowing the females just for a couple of days, harvesting their eggs with hormonal induction using oxytocin, the same hormone we use for humans. And once they've laid their eggs, the mama turtles go back to the river and then those eggs stay in the lab in the incubator to get through and thereby bypassing the foxes, the eggs take a couple of months to hatch. So that's in partnership with the University of New England."

La dottoressa Streeting ha affermato che il programma congiunto ha avuto un successo incredibile, producendo quasi 4.000 cuccioli di tartaruga in pochi anni.

"It takes 60 days for the babies to hatch out, and then those babies return to the waterways. Just this season, we've produced 1,085 babies, and during our program over the last few years, we've produced now just over 3,800 hatchlings and returned them to the waterways."

L'altro metodo utilizzato dall'università e dai Servizi territoriali locali consiste nel proteggere i siti di nidificazione stessi.

"So actually finding nests and protecting them individually with wire mesh, and also putting temporary electric fences around prime nesting areas to deter foxes. And those nest protection methods have been proving really, really successful. In fact, just this season at one of our sites, one of the electric fences has protected 37 nests, and if you consider that on average a bell turtle nest will have about 20 eggs, that means a lot of baby turtles going back into the waterways from those protection efforts."

Per Martin Dillon è quasi impossibile tenere completamente lontane le volpi, ma la recinzione elettrica può aiutare a farle andare altrove.

"They're pretty simple. They have a solar energizer that provides a charge. And when a fox comes along and pokes its head or brushes against a fence, it gets a deterrent shock. And you can't exclude foxes with fences. They're just too cunning, they'll find a way. But what these fences do is create an aversion for the foxes. And so those really good nesting areas where we can protect them with an electric fence, the fox soon learns to go, 'You know what? That's too hard. I'm going to keep on moving and go somewhere else.'"

Mentre le volpi rimangono il nemico principale della tartaruga di Mary River, nel Queensland sudorientale, questa specie bizzarra ha dovuto affrontare minacce storiche da parte dell'uomo che hanno portato la sua popolazione vicino all'estinzione.

Negli anni Sessanta e Settanta la raccolta di uova era dilagante, poiché le tartarughe erano un animale domestico molto diffuso in Australia.

Circa 15.000 uova venivano inviate ai negozi ogni anno, con il nome di “penny turtle”, “tartaruga da un centesimo”.

La dottoressa Mariana Campbell, docente di ricerca presso la Charles Darwin University, afferma che questo ha avuto un impatto significativo sul loro numero.

"It had a significant decline in population during the 1960s and early 70s. The turtles were sold in Australia across all the pet shops. And in 1994, the species was identified and at that time we already had these very low population on the lower catchment of the Mary River."

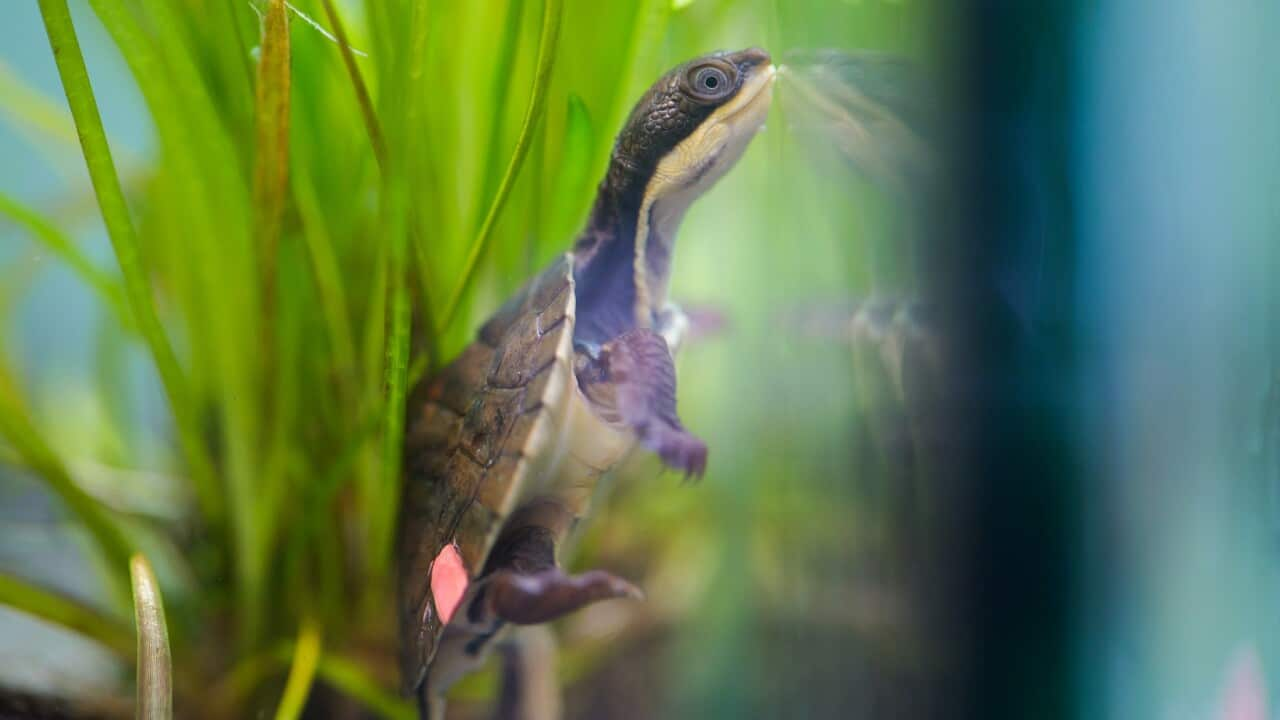

La specie, in pericolo di estinzione, è spesso chiamata “tartaruga dai capelli verdi” o “tartaruga punk”, a causa delle alghe che le crescono sulla testa, formando a volte una pettinatura simile a quella di un mohawk.

Mentre il numero di femmine riproduttive è diminuito del 95% tra il 1970 e il 2000, la dottoressa Campbell ha affermato di aver assistito in prima persona a come i gruppi comunitari e i Proprietari Tradizionali abbiano contribuito a invertire la tendenza.

"I have been involved with the community group up in the Mary River for almost 20 years now, and I know that nothing can replace that. The local engagement, the local knowledge and the passion that they have for their backyard. We have had direct liaison with some of the indigenous people around the area for the same reason that is traditional knowledge that has been passed down. It can't be replaced in any way."

Secondo l'autrice, questi sforzi hanno fatto sì che ogni anno migliaia di giovani tartarughe del Mary River rientrino nel fiume.

Inglese

After an important hatching season, conservationists like Billy Collett are celebrating progress made toward saving Australia's endangered freshwater turtle species from extinction.

His organisation, Aussie Ark, has been breeding three different species at the Australian Reptile Park in Somersby, New South Wales.

"So exciting. 48 Hunter River turtle eggs, 39 Bell's turtle eggs, and a whopping 85 Manning River turtle eggs. We will care and look after these beautiful little hatchlings until they're bigger and stronger, and then we can return them back out into the wild rivers where they belong."

He says programs like this come at a time when the ancient animals are under unique threat levels.

"These turtles literally date back millions of years to the age of the dinosaurs and now they're facing extinction, which is really upsetting. So, that's why this project is absolutely critical for the survival of the species."

But why exactly are these turtles under threat?

Martin Dillon is the Senior Land Services Officer at the Northern Tablelands Local Land Services and leads an operation to protect the local population of Bell's turtles, which are found exclusively in northern New South Wales.

He says the species has been pushed to the brink in recent years by invasive predators.

"European foxes are raiding almost all of their nests. So Bell's turtles lay their eggs buried in the stream bank, really close to the water's edge, actually within a few meters. And they're naive to foxes. They haven't evolved with foxes. And foxes are just super efficient and they train their cubs to patrol the riverbanks during the nesting season, find those packets of protein and just eat them up. And so what happens is, although turtles are long lived and they're really tough and they're really robust, there's not enough recruitment to sustain the population."

Dr Lou Streeting from the University of New England, says currently more than 95 per cent of Bell's turtle nests are raided, due in part to the particularly hands-off parenting approach of turtles.

"With turtles, they don't have maternal care, so they deposit their eggs on the riverbank and the female returns to the water. The eggs are very vulnerable to foxes."

Mr Dillon says his team has two different approaches to protecting the baby turtles, the first of which involves removing the eggs from the threat of foxes.

"Borrowing the females just for a couple of days, harvesting their eggs with hormonal induction using oxytocin, the same hormone we use for humans. And once they've laid their eggs, the mama turtles go back to the river and then those eggs stay in the lab in the incubator to get through and thereby bypassing the foxes, the eggs take a couple of months to hatch. So that's in partnership with the University of New England."

Dr Streeting says the joint program has been incredibly successful, producing close to 4000 baby turtles in just a few years.

"It takes 60 days for the babies to hatch out, and then those babies return to the waterways. Just this season, we've produced 1,085 babies, and during our program over the last few years, we've produced now just over 3,800 hatchlings and returned them to the waterways."

The other method the university and Local Land Services are using involves protecting the nesting sites themselves.

"So actually finding nests and protecting them individually with wire mesh, and also putting temporary electric fences around prime nesting areas to deter foxes. And those nest protection methods have been proving really, really successful. In fact, just this season at one of our sites, one of the electric fences has protected 37 nests, and if you consider that on average a bell turtle nest will have about 20 eggs, that means a lot of baby turtles going back into the waterways from those protection efforts."

Martin Dillon says it's nearly impossible to keep foxes out completely, but the electric fence can help to redirect them.

"They're pretty simple. They have a solar energizer that provides a charge. And when a fox comes along and pokes its head or brushes against a fence, it gets a deterrent shock. And you can't exclude foxes with fences. They're just too cunning, they'll find a way. But what these fences do is create an aversion for the foxes. And so those really good nesting areas where we can protect them with an electric fence, the fox soon learns to go, 'You know what? That's too hard. I'm going to keep on moving and go somewhere else."

And while foxes remain a prime enemy of the Mary River turtle in southeast Queensland, the quirky species has faced historic threats from humans that has left their population close to extinction.

In the 1960s and 1970s egg harvesting was rampant as turtles were a popular pet in Australia.

About 15,000 were sent to shops every year, branded as the "penny turtle".

Dr Mariana Campbell, a research lecturer at Charles Darwin University, says this had a significant impact on their numbers.

"It had a significant decline in population during the 1960s and early 70s. The turtles were sold in Australia across all the pet shops. And in 1994, the species was identified and at that time we already had these very low population on the lower catchment of the Mary River."

The critically endangered species is often called the "green-haired turtle" or the "punk turtle", due to the algae that grows on its head - sometimes forming what looks like a mohawk-like hairdo.

While the number of breeding females fell 95 per cent between 1970 and 2000, Dr Campbell says she's witnessed first-hand how community groups and Traditional Owners have helped turn the tide.

"I have been involved with the community group up in the Mary River for almost 20 years now, and I know that nothing can replace that. The local engagement, the local knowledge and the passion that they have for their backyard. We have had direct liaison with some of the indigenous people around the area for the same reason that is traditional knowledge that has been passed down. It can't be replaced in any way."

She says these efforts have resulted in thousands of young Mary River turtles re-entering the river again every year.